Table of Contents

Citation: Grema, M. (2024). Nativazation of Hausa Loanwords in Kanuri through Deglottalization and Sonorization. Tasambo Journal of Language, Literature, and Culture, 3(1), 45-51. www.doi.org/10.36349/tjllc.2024.v03i01.006.

Nativazation of Hausa Loanwords in Kanuri through Deglottalization and Sonorization

Musa Grema

Department of

Languages and Linguistics,

Yobe State

University,

KM7, Gujba Road

Damaturu, Yobe State

GSM: +2348067273233

gremamusa2012@gmail.com

Abstract

The paper attempts to identify and study those linguistic

items borrowed from Hausa to Kanuri language with special attentions to the

deglottalization and sonorization processes employed in incorporating the loanwords.

Borrowing is a phenomenon which is as old as human social, economic, and

administrative contact. When a contact is established between two or more

different linguistic communities, there is the tendency for linguistic

borrowing to take place. Therefore, despite the fact that Hausa belongs to Chadic

family and Kanuri belongs to Nilo-Sahara, there exists linguistic borrowing

between them. The paper focuses on the deglottalization and sonorization in

nativazation of the borrowed words. The

research sought data from two sources. These sources are primary and secondary.

The primary source includes unobtrusive observation when discourse is taking

place in Kanuri language. Similarly, the researcher’s intuition plays

significant role in identifying the loanwords being a native speaker of the

language. On the other hand, the secondary sources include written records,

such as journal articles, dissertations, thesis, dictionaries etc. The paper concludes that Kanuri, a

Nilo-Saharan language uses deglottalization and sonorization in nativazation of

some Hausa borrowed lexical items. This resulted in making the loanwords to

behave like the native words of the target language (Kanuri).

Keywords:

Loanwords, Nativization,

Deglottalization, Consonant and Sonorization

Introduction

Despite the fact that it is not easy to find a universally

accepted definition of borrowing, the paper makes an attempt to review some

definitions put forward by different scholars. Let’s begin with Haugen (1950,

p. 212), that views linguistic borrowing

as “the attempted reproduction in one language of patterns previously found in

another”. On the other hand, Thomason

and Kaufman (1988, p. 37) consider it as the incorporation of foreign features

into a group's native language by speakers of that language; the native

language is maintained but is changed by the addition of the incorporated

features.

In the words of

Bussmann (1998, p. 139) borrowing is seen as adoption of linguistic expressions

(which can be lexical item, phrase or both) from one language into another,

usually in a situation when no term exists for the new object, concept or state

of affairs. Similarly, Yul-Ifode (2001) cited in Nneji and Uzoigwe (2013, p. 9)

maintains that, the concept of borrowing simply means an aspect of lexical

change. However, this process involves adding new items to a language or

dialect by taking them from another language or dialect. From these, therefore,

it can be seen as a one of the linguistic processes that improves the lexicon

of the language. It can also be deduce

d

that there is tendency

where a borrowing can take place even within different dialects of the same

language.

Turning to the

languages under study; both Hausa and Kanuri are African languages which are

spoken as mother tongues and second languages by huge number of people.

According to Greenberg (1966) Hausa is a member of the Chadic languages which

belongs to the Afro-Asiatic phylum, while Kanuri is classified as a member of

the Saharan branch which belongs to the Nilo-Saharan phylum. Both Hausa and

Kanuri have geographical and social dialects. Despite the fact that Hausa and

Kanuri belong to different language phyla, there exist borrowings of linguistic

item(s) between them, because there is contact between the speakers of the

languages for several decades.

Lohr, Ekkehard & Awagana (2009) assert that it is assume

that Chadic languages may have had a long history of geographical neighborhood

with different languages which belong to different language phyla. They are

neighbor

to Benue-Congo languages to the south and west, it is also

established that they are

neighbor

to Saharan

languages to the east and north.

Therefore,

the paper focuses

on the deglottalization and sonorization as a means of nativazation of Hausa

loanwords in Kanuri.

Similarly, it is

clear that both Hausa and Kanuri are tonal languages. In view of this, in all

the examples used in this research low and fallen tones are marked, while high

tones are left unmarked. Similarly, long vowels are indicated by doubling the

concern

ed

vowel.

There is no doubt

that a lot of research has been conducted on phonological behaviour of Hausa

loanwords in Kanuri which include Lang (1923–1924), Baldi (1992, 1995),

Bulakarima (1999), Shettima & Abdullahi (2000), Lohr, Ekkehard &

Awagana (2009), Grema (2017) among others. However, to the best of my knowledge

none of the works mentioned dwelt so much on deglottalization and sonorization

as device of nativazation of Hausa loanwords in Kanuri. This pave

s

a way to the present research in order to breach the

academic gap left.

Brief Account of Contact between Hausa and Kanuri

The relationship

between Hausas and Kanuris began well before the fifteenth century during the

reign of Mai Ibrahim B. Uthman, as a result of military encounter.

At that time Hausa

must have played some role as a commercial lingua franca in the Hausa states

which are geographically adjacent to the west of Borno. Similarly

,

intermarriage might also play a little role couple with the

situation where both speakers of the languages share the same common impact of

Arabo-Islamic culture and urban medieval civilization on the other hand.

Bilingualism also played a major role which becomes more widespread in the

recent contact which began during the colonial period and Hausa became the

dominant lingua franca of northern Nigeria.

Apart from the military encounter between Hausa States

and Kanem Borno, there were also other forms of relationship that existed

between them. One of such relationships was the arrival of a very powerful

Bornoan immigrant to the city of Kano during the reign of Sarkin Kano Dauda

ɗ

an Kanajeji in the fifteenth century (Usman, 1983 and

Lohr, Ekkehard

& Awagana 2009

).

Similarly, during the reign of Sarkin Kano Muhammadu

Kisauki, another group of immigrants from Borno came to Kano under the

leadership of ‘Goron Duma’. This group of immigrants settled near ‘Kurmi’

market. The migrations of learned men from Borno were also witnessed in Zazzau

and Katsina

(Usman, 1983

)

.

Amongst the factors that encourage travels and

relationships between Hausa States and Borno were environment and economy. They

buy and sell commodities from one another. Potash, salt, hides and skin were

among the items of trade between them. Usman (1983) also adds that Borno was

regarded as a major source of horses supply to Hausa states.

In view of these, one would understand that there has

been a relationship between the Hausa and Kanuri speakers for many centuries.

To further buttress this point, Brann (1998) states that it is likely that some

Hausa pilgrims, traders and scholars came to Ngazargamu and later to Kukawa on

their way to the Holy city of Mecca, and some of them subsequently settled

there.

This indicates that,

there was much contact between the Hausas and the Kanuris and eventually the

Kanuris adopted the Hausa language and much of their culture. This has

contributed immensely to the considerable regional homogeneity found in the

northern states of Nigeria today. It is also worth mentioning that

after independence

of Nigeria and Niger, which are considered as dominant areas of Hausa and

Kanuri speakers, Hausa gained considerable dominance in the spheres of

commercial activities, politics and administration, education, and the media.

Methodology and Model of Approach

Going by the nature of this research it is regarded as

qualitative and synchronic since it focuses on the study of nativazation of

Hausa loanwords in Kanuri through deglottalization and sonorization. The

research work sourced its data through two different sources; namely primary

and secondary. The primary source involved unobtrusive observation by the

researcher. The researcher’s intuition is also of great importance in gathering

the data from the field. Written records such as journal articles, thesis, dissertations

and dictionaries are used as secondary sources of data. Similarly, in the

process of gathering the data many Hausa loanwords in Kanuri are identified but

only those that are relevant to the present research are used as examples. More

so, the paper adopts Yalwa (1992) as a model of approach. Having said that,

let’s briefly look at how he approach the issue phonologically. Therefore,

Yalwa (1992) reveals that, Hausa people borrowed a lot of Arabic words from

Arabs through trade and the religion of Islam.

He succeeded in

discussing the phonological evidence of Arabic loans in Hausa. He observed that

in some of the Arabic loans in Hausa there are cases where Arabic /f/ is

sometimes realized as /b/ intervocalically, word finally or after semi vowel

followed by another vowel in Hausa. But this change does not apply to the most

recently Arabic loans in Hausa. The following examples are provided:

|

ARABIC

|

HAUSA

|

GLOSS

|

|

al-kìtàab |

littaafîi

|

book |

|

al-Gayb |

lâifii/aibìi |

fault |

He also presented

the following general rule to account for this change.

Ar: b > H: f/

[v – v]; [v

-

#]; [G – V] or [G – C]

He further raises

the issues of neutralization, voicing, glottalization, vowel lengthening and

shortening processes in the process of nativization of Arabic loans in Hausa.

He clearly states that velar consonants are palatalized before front vowels and

labialized before back vowels. In some Arabic loans in Hausa the vowel /o/

changes to schwa /

ə

/ which is

regarded as morphophonemic. He provides this example:

|

ARABIC

|

HAUSA

|

GLOSS

|

|

al-kohl |

kwâllii

[kw

ə

llii] |

antimony

chloride |

There is also what

he terms as split process where a single sound in Arabic changes to other

sounds in Hausa in the process of borrowing, he cites many instances of such

phenomenon. For instance,

Arabic

/s/ -

Hausa s, š/ [#.....] or [V] #

[-low]

[-back]

The

following examples are also provided:

|

ARABIC

|

HAUSA

|

GLOSS

|

|

saba’in |

sàbà’in |

seventy |

|

nafs

(soul) |

numfaashii |

breath,

breathing, soul |

Finally Yalwa

(1992) states that among the Arabic laryngeals and pharyngeals Hausa has only

/h/. Therefore, where Arabic /h/ or /x/ occurs it is only realized as /h/ in

Hausa. The Arabic /

ʕ

/ is changed to

glottal stop /

ʔ

/ in Hausa even

though it is believed to have been borrowed from Arabic. But according to him

there are some instances where the sound /

ʕ

/ or /

ʔ

/ is replaced with /w/ consider this example

ʔ

allaf > wallàfaa (to compose/publish a book/paper/poem).

Thus, this paper will adopt the model of approach of

Yalwa (1992) as mentioned earlier.

Data Presentation and Analysis

In this section of

the paper, the data collected for the research is presented and analyzed. Thus,

an explanation is going to be presented on how Kanuri language deglottalized

and sonorized some segments in the process of incorporation of Hausa loanwords.

Deglottalization

The phenomenon of replacing a segment of the source

language with another segment in the target language is highly productive in

linguistic borrowing. When a borrowed word contains a phoneme which is absent

in the target language, it is usually replaced with a close

correspondence. This act paves way to

various phonological processes to take place, among which is Deglottalization.

Hausa has nine (9) glottalized consonantal sounds out of which only one (1) is

found to be existing in Kanuri language; namely glottal, stop (/

ʔ

/). Glottalized phonemes in the Hausa words loaned

into Kanuri are deglottalized in order to suit into the phonological system of

the target language. As a result

[

ɓ

]

>

[

b

]

,

[

ƙ

]

>

[k], [

ƙ

w] > [kw]/, [

ɗ

] > [d], [’y] > [y] and [s’] > [s]. Let us

consider the following examples:

Example 1:

|

(a) |

Hausa

|

Kanuri

|

Gloss

|

|

ɓ

àrnaa |

/bànna/ [bànna] |

spoilage/damage |

Let us formulate rules for the above examples, as follows:

Rule 1: Deglottalization Rule

1a:

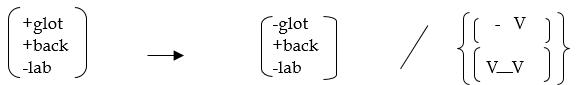

Rule 1a converts glottalized bilabial implosive /v/ into nonglottalized bilabial stop [b] before a vowel in the borrowed word, as in example (1a). In this case the phenomenon takes place word initially. However, base d on the data collected for the research , this is the only example found, there are also other instances where only one example is found, which can be seen later. Apart from the deglottalization there is also a case of consonant substituiton where a consonant / r / in Hausa is subtituted with /n/ in Kanuri and vowel laxing as can be seen in the example above .

Example 2:

|

(a) |

Hausa

|

Kanuri

|

Gloss

|

|

ƙ

oosai |

/kosai/

[kwosai] |

bean cake |

|

|

(b) |

ƙ

uusàa |

/kusà/

[kwusà] |

rubber |

|

(c) |

dan

ƙ

òo |

/dankò/[dankò] |

rubber |

|

(d) |

ƙ

òo

ƙ

oo |

/kòko/ [kwòkwo] |

type of small calabash |

|

(e) |

ƙ

òo

ƙ

arii |

/kòkoli/[kwòkwoli] |

effort, try |

|

(f) |

ƙ

àn

ƙ

araa |

/kankara/[kankara] |

ice block |

Consider the below phonological rule for the above examples.

1b:

Turning to rule 1b, it accounts for the

conversion of the glottalized velar ejective /

ƙ

/ into nonglottalized

velar stop [k], as in examples (2a – f) respectively. However, in examples (2a

and b) the conversion takes place word initially while in example (2c) it takes

place word medially. More so, in examples (2d – f) the deglottalization takes

place word initially and medially. Thus, the phenomenon of deglottalization in

Hausa loanwords in Kanuri occur word initially and word medially as justified

by example 2 above.

E

x

ample

3:

|

(a) |

Hausa

|

Kanuri

|

Gloss

|

|

ɗ

an ciki |

/dankiki/

[dankjikji] |

inner wear |

Let us formulate a phonological rule to

capture the above deglottalization process.

1c:

Rule 1c above,

say

s voiced glottalized implosive /

ɗ

/

is realise as

nonglottalized

voiced alveolar stop [d] in word initial position before a vowel as seen in

example (3a).

Example 4:

|

(a) |

Hausa

|

Kanuri

|

Gloss

|

|

‘y

ar ciki |

/

j

arkiki/ [

j

arkjikji] |

inner wear |

This situation of deglottalization can be

represented through the below phonological rule.

1d:

Rule 1d on the other hand converts palatalized-glottal stop /’y/ into nonglottalized palatal approximant [j] word initially before a vowel as in example (4a).

E

x

ample

5:

|

(a) |

Hausa

|

Kanuri

|

Gloss

|

|

ts

àngayàa |

/sàngayà/

[sàngayà] |

qur’anic school |

|

|

(b) |

ts

aamiyaa

|

/samiya/ [samiya] |

a type of Hausa royal gown |

Let us formulate rules for the above

examples, as follows:

1e:

Rule 1e accounts for the conversion of voiceless alveolar

ejective /s’/ into voiceless alveolar fricative [s] word initially before a

vowel which is also a form of deglottalization, as in examples, (5a and b).

Sonorization

Chomsky and Halle (1968, p. 302) define sonorant as

“Sounds produced with a vocal tract cavity configuration in which spontaneous

voicing is possible.” In other words

,

Crystal (2008, p.

442) describes the word sonorant as one of the major class features of sounds produced distinctive feature

theory, in order to handle the variations in manner of articulation. Thus,

sonorants are sounds produced with a relatively free air-flow, and a vocal fold

position such that spontaneous voicing is possible as in vowels, liquids and

laterals. Based on the foregoing discussion one can describe sonorization as a

form of consonant weakening (lenition) where an obstruent is replaced with a

sonorant sound in a certain phonological environment. Abubakar (2008, p. 1)

observes that weakening in Kanuri language affects intervocalic non-nasal obstruent

automatically without any restriction and it is realized either through

assimilation or deletion process. Interestingly, in the case of Hausa loanwords

in Kanuri the phenomenon takes place inter-vocalically and the affected sounds

are either voiced stop or voiceless stop. This phonological observable fact is

considered as a regular and productive process in Kanuri. This phenomenon is

noticed as one of the processes involved in incorporating Hausa words loaned

into Kanuri, where /b/ and /k/ in the Hausa words are replaced with /w/ word

medially. In case of the former it can be seen in example 6a - i while the latter is evident in example 6j.

Consider the examples below:

Example 6:

|

(a) |

Hausa

|

Kanuri

|

Gloss

|

|

àyàbà |

/àyàwà/ [àyàwà] |

banana |

|

|

(b) |

dubuu

|

/duwu/ [duwu] |

one thousand |

|

(c) |

laabulee

|

/lawule/ [lawule] |

curtain |

|

(d) |

riibàa

|

/riwà/ [riwà] |

profit |

|

(e) |

taabàa

|

/tàwa/

[tàwa] |

tobacco/cigarette |

|

(f) |

kabàrii

|

/kawùrì/ [kawùrì] |

grave |

|

(g) |

kallabii

|

/kallawi/ [kallawi] |

head tie |

|

(h) |

tàttabàraa

|

/tàttawàr/ [tàttawàr] |

pigeon |

|

(i) |

kwalbaa

|

/kolwà/ [kwolwà] |

bottle |

|

(j) |

bàrkònoo

|

/bàrwùno/ [bàrwùno] |

chili pepper |

Let us formulate rules for the above example:

Rule 2: Sonorization Rule

Rule 2a converts voiced, bilabial, stop /b/ into bilabial

resonant [w] between two vowels in a word medial position as seen in examples (6a,

b, c, d, f, g and h). It also converts voiced, bilabial, stop /b/ into bilabial

resonant [w] between a consonant and vowel in a word medial position as seen in

examples (6i). Rule 2b converts voiceless velar stop /k/ into a semi vowel with

feature specification [+ lab] in between consonant and a vowel word medially as

in example (6j). Despite the fact that in the previous examples (6a – h) it is

[b] > [w] but in example (6i) one can notice that it is [k] > [w], this

phenomena is also form of consonant weakening. The weakening of bilabials and

velars intervocalically and post-liquid consonant environments is an automatic phenomenon

in Kanuri, consider example (6i and j). Thus, it is mandatory for the loanwords

to behave like the native Kanuri words before they are fully integrated in the

target language.

Conclusion

Based on the foregoing discussion, it is noticed and

established that Kanuri, a Saharan language and one of the African languages

borrowed some le

x

ical items from

Hausa, which is a Chadic Language and also one of the widely spoken languages

in Africa. An attempt is made to show

that, the borrowed words were absorbed into the phonological system of the

target language (Kanuri). In the process of incorporating the Hausa loanwords phonologically,

it is established that deglottalization and sonorization processes are

involved. In all

the examples cited glottalized phonemes are deglottalized. Voiced, bilabial

implosive [

ɓ

]

becomes voiced bilabial stop

[b]

and also voiceless, velar ejective

[

ƙ

]

becomes voiceless, velar stop

[k]

among others. In the same vein, a case of consonant weakening

which is considered as form of sonorization is also evident in incorporating

Hausa loanwords in Kanuri. In this situation a voiced, bilabial stop

[b]

becomes voiceless, velar approximant

[w]

and also voiceless, velar stop

[k]

becomes voiceless, velar approximant

[w]

.

References

Abubakar, A. (2008). Parameters of consonant weakening in

Kanuri.

MAJOLLS: Maiduguri

Journal of Linguistic and Literary Studies

X

.

1-9.

Baldi, S. (1992).

Arabic loanwords in Hausa via Kanuri and Fulfulde. In Ebermann,

Erwin & Sommerauer, Erich R. & Thomanek, Karl E.

(eds.), Komparative Afrikanistik

(Festschrift Mukarovsky)

, (Pp. 9–14).

Baldi, S. (1995).

On Arabic loans in Hausa and Kanuri. In Ibriszimow, Dymitr &Leger, Rudolf

(eds.), Studia Chadica et Hamito-Semitica: Akten des Internationalen

Symposions zur Tschadsprachenforschung

, (Pp. 252–278).

Bloomfield, L.

(1933) Language. Holt, Reinhart & Winston.

Brann, C. M. B. (1998). The spread of Hausa in Maiduguri.

University of Maiduguri Inaugural Lecture Series.

Bulakarima

, S. U. (1999)

.

Kanuri loanwords in

Guddiranci

.

MAJOLLS: Maiduguri Journal of Linguistic and Literary Studies 1

.

61-70

Bussmann, H. (1998). Routledge

dictionary of languages and linguistics, Gregory T. & Kerstin K. (eds).

Routledge.

Chomsky, N. & Halle, M. (1968). The sound pattern of English. Harper & Row Publishers.

Crystal, D. (2008). Dictionary

of linguistics & phonetics. Blackwell Publishing.

Löhr, D., Ekkehard, H. W. & Awagana, A. (2009).

Loanwords in Kanuri, a Saharan language In

Martin Haspelmath and Uri Tadmor (eds.),

Loanwords in the world’s

languages a comparative handbook

. De Gruyter Mouton

Greenberg,

J. H.

(196

6

)

.

Languages of Africa

. The Hague, Mouton

.

Grema, M. (2017). Vowel laxing as a technique in Hausa

words loaned into Kanuri. Yobe Journal of

Language, Literature and Culture 5, 97-100.

Haugen, E. (1950).

The analysis of linguistic borrowing. Language 26, 210–231.

Lang, K. (1923/1924).

Arabische lehnwörter im Kanuri [Arabic loanwords in Kanuri]. Anthropos 18/19,

1063–1074.

Nneji, O. M. & Uzoigwe, B. C. (2013). Globalization

and Lexical Borrowing: The Igbo Example. A paper presented at Igbo Studies

Association (USA).

Shettima, A. K. and Abdullahi, S. A. (2000). Vowel epenthesis in Kanuri loanwords.

FAIS Journal of Humanities 4 No 1.

Thomason, S.G.

& Kaufman, T. (1988). Language contact, creolization and genetic

linguistics. University of California Press.

Usman, Y. B. (1983). A reconsideration of the history of relationship

between Borno and Hausaland before 1804. Usman, B. and Alkali, N. (eds.), Studies in the History of Pre-Colonial

Borno. Northern Nigerian Publishing.

Weinreich, U.

(1953). Languages in contact. Mouton.

Yalwa, L. D. (1992). Arabic loanwords in Hausa.

Journal of the African Activist Association XX (III) Special Issues on

Afro-Arab. 101-131.

Appendix

Abbreviations, Sings and Symbols

Signs, Symbols and Abbreviations Used

+ → Positive

sign

→ → Becomes

[ ]

→ Square brackets enclose phonetic

features or symbol

/ / → Oblique strokes enclose base form or underlying representation of an element

## → Word

boundary

/ → in

the environment of

> →

Becomes

___ → Position/location

of input

{ }

→ Braces indicate choice

´ → High

tone

` → Low

tone

- → Negative

sign

ant → Anterior

C → Consonant

cons →

Consonantal segment

cont →

Continuant

del.rel →

Delayed Release

glot →

Glottality

lab → Labiality

pal → Palatality

syll →

Syllabic

V → Vowel

0 Comments

ENGLISH: You are warmly invited to share your comments or ask questions regarding this post or related topics of interest. Your feedback serves as evidence of your appreciation for our hard work and ongoing efforts to sustain this extensive and informative blog. We value your input and engagement.

HAUSA: Kuna iya rubuto mana tsokaci ko tambayoyi a ƙasa. Tsokacinku game da abubuwan da muke ɗorawa shi zai tabbatar mana cewa mutane suna amfana da wannan ƙoƙari da muke yi na tattaro muku ɗimbin ilimummuka a wannan kafar intanet.