This article is published by the Zamfara International Journal of Humanities.

By

Wada Richard Sylvester1 Wappa John Peter2 & Livinus Ruth3

1,2,3Department of English Language Education,

School of Continuing Education,

Adamawa State Polytechnic Yola,

Adamawa - Nigeria.

Abstract

The Higgi language has about six hundred and twelve thousand three hundred and eighteen thousand (612,380,000) speakers going by the 2006 Nigerian national population census. The Higgi people are in Adamawa state Nigeria and some parts of the republic of Cameroon. The language is a part of the Chadic language. The study identifies the fact that a tone language draws meaning from a change in the pitch during articulation. A change in a pitch/tone when articulating a particular word brings about a change in meaning. This study intends to educate Higgi language speakers and those who have interest in the study of the language and also educate people on the effect of tone on meaning relations in Higgi language. Controversies abide in Higgi language owing to dialectical variations, but this study focused strictly on Bazza dialect of the language. Data for the study was collected using the random sampling technique. Thirty lexical items were word listed out of which ten lexical items were picked for the analysis. Data for the study was analysed using the discursive method of data analysis.

Background of the study

The Higgi people of Adamawa state, Nigeria, have a very interesting life. The home of the Higgi people is found in Michika local government. The language spoken by the Higgi people is Higgi. Controversies trail the language name because of dialectical variations. There are about eight dialects of the Higgi language. Some of the dialects are mutually intelligible, while others are not. The Dakwa (Bazza) dialect is mutually intelligible to the Nkaffa dialect. The people of the Nkaffa dialect prefer to be referred to as ‘Kamwe’ meaning people of the mountain. On the other hand, the Dakwa dialect version of Kamwe is ‘A’ghuma’ meaning people of the mountain. The Higgi language belongs to the Biu-mandara group of the Chadic phyla of the language classification. The study identifies that the language is a tonal language, hence investigates the role tone play in the

determination of meaning in lots of lexical items in the language.

There are about 70% of world’s languages that are tonal (Yip, 2002). The tonal languages are spoken by huge number of people and are in geographically diverse countries. The Mandarin Chinese speakers are about eight hundred and eighty-five million speakers (Xu, 1994). The Yourba language has about twenty million speakers. The core of this study is the Higgi language and the language has about six hundred and twelve thousand three hundred and eighteen thousand (612,318,000) speakers going by 2006 Nigerian national population census. A language is tone language if the pitch of the word can change the meaning of the word. The change in meaning is not just in the nuances, but the core meaning can also be affected. In Higgi language, a change in meaning of a word occurs by a change in pitch in the

pronunciation of a word both at the lexical and sentential level. A language with tone is one which an indication of pitch enters into the lexical realization of at least some morphemes. The definition is designed to include accentual languages (Belvin, 1993) as a sub type of tone language in which words have one tone or no tones and the tone is associated with a particular syllable or more. It is necessary that

this study educates us on tonal systems and how to read them.

There is no consensus on how to transcribe tones. Different parts of the world have different systems well suited to their own areas. In Africa, a set of accent are used to convey tones, while in Asia and the Mesoamericans digits are used. The chart below is an example.

History of the Higgi people

The Higgi, like other ethnic groups in Nigeria, claim eastern origin. Oral tradition indicates that the people migrated from Nchokyili in the present day Republic of Cameroon. According to this tradition, it was in Nchokyili that the people moved to settle in their present geographical location. It is said that the Higgi left Nchokyili together with other ethnic groups such as Sukur, Marghi, Fali, Holma and Yungur. In this tradition of origin, we are not told when the people left Nchokyili, nor are we given the reasons for their migration. However, according to Baba Maduwa, the Higgi came from Egypt and first settled at Mokolo presently located in Cameroon very close to the border between Nigeria and Cameroon. Note that the Mokolo in Cameroon is different from Mukula (the spiritual centre of the Kamwe) in Dakwa-Bazza, Nigeria. The Higgi people settled down in their present geographical location at Nkafa (Michika) and Dakwa (Bazza) which are considered as the two main clusters of the Higgi nation and this happened through gradual movements along the plains of the Mandara Mountains’ range.

The Higgi are the group of people who occupy the central slopes of the Mandara Mountains in the central and Western part of Africa. The ancestral land of the Higgi people stretches

from Mubi in the Southern axis of Mandara Mountains to Shuwa and Koppa in Madagali Local Government Area of Adamawa State, Nigeria to the North. Westwards, it extends from Samuwa in Lassa, Askira/ Uba Local Government Area of Borno State Nigeria to the Republic of Cameroon in the East as far as Magode and Rhumisiki towns. In terms of land mass, the Kamwe inhabits an area of about 2714.6 square Kilometres. In diameter, it is approximately 56.32KM from Lassa to Magode from the west to the east. It is also about 48.2KM from Koppa/Shuwa to Ghye (Zah). The Higgi land like other parts of Central Nigeria and Northern Cameroon is located in the Sudan savanna.

Aim and objectives of the study

The aim of the study is to analyze the role of tones in the determination of meaning of lexical items in Higgi language. The will be achieved through the following objectives.

Investigating the roles of tones in meaning relations in tonal languages.

Determining the importance of intonation the articulation of words in a given language.

Literature review Phonetics and phonology

Phonetics and phonology work hand in hand. They both share the main subject of oral human

communication, but they differ in their approaches. Advanced Dictionary (2001:1153) defines both phonetics and phonology as” the study of speech sounds” and then adding to distinguish phonology from phonetics “phonology is the study of speech sounds in a particular language’. Phonology is the language system and the rules that govern them. Language uses vast number of sounds, all of which phonetics can describe. Phonology sorts through the sounds and asks which of them play a role in communication. Phonology seeks to find out which sounds can be combined into words. Phonetics is concerned with the production of speech sounds. Phonetics investigates the organs that are involved in the speech processes, their anatomy and how they function. The interest of phonetics is the speech sounds and their acoustic properties. It focuses on how vowels and consonants of human languages differ from each other.

Tones and intonations

A full understanding of tone needs an understanding of how sounds are converted into a precise phonetic implementation. A central question is whether every syllable has a specification for tone at the end of the phonology, or whether some are unspecified, and acquire their surface pitch by interpolation from surrounding tonally-specified syllables, which serve as targets. Many tonal changes have clear roots in phonetics. Two phenomena suffice – declination and peak delay – are of interest here because they have been phonologized in many languages. The phonologization of declination is extremely widespread, especially in Africa, where it has given rise to a phonological process called down drift by which high tones are drastically lowered after low tones. Turning to peak delay, in Yoruba (Akinlabi and Liberman 2000), peak delay has developed into a phonological process that turns a highlow sequence into a high-falling sequence by spreading the high tone. Rárà (H.L) → rárâ (H.HL) ‘elegy’. More generally, tone spread or shift to the right is very common, but tone shift or spread to the left is much rarer. Just like segmental contrasts, tonal contrasts can be affected by co-

articulation effects (Peng 1997, Xu 1994). The laryngeal articulators have their own inertia, and it takes time for change to take place. Hearers seem well able to compensate for these effects, and continue to recognize the tones, but nonetheless caution must be observed in deciding whether some particular tonal effect is phonetic or phonological, and the answer is not always clear (Kuo, Xu, and Yip). We do know that infants mimic the pitch contours of the ambient language very early, and this applies to lexical tone as well as intonation, so the inventory of contrastive tones is acquired early. Children successfully master lexical tonal contrasts by around their third year, earlier if the language does not have too many alternations. They produce the tones quite accurately at a stage when some adult-like segmental production is still eluding them.

Tones

“Tone is the use of pitch in language to distinguish lexical or grammatical meaning – that is, to distinguish or to inflect words. All verbal languages use pitch to express emotional and other paralinguistic information and to convey emphasis, contrast, and other such features in what is called intonation.”

Duanmu (2004) claimed that a tone language has “lexical tones”, which “is a pitch contour that is not predictable from other phonological properties, such as stress or segmental features, and can distinguish word meanings”. It also has boundary tones (occur at certain syntactic boundaries) but it does not have “pitch accent” (is aligned with a stressed word). In a tone language, stress is not very obvious, and it has a down step effect.

Tone is a phonological category that distinguishes the meaning of words or utterances (Gussenoven 2004). It is a suprasegmental feature realized on syllables for the distinction of meaning. According to Pike (1948) “A tone language is one in which contrastive pitch levels do not merely form the intonation tune of a sentence but enters as a distinctive factor into the lexical elements of the language”. In other words, tone distinguishes between the meanings of words with otherwise identical phonemic composition.

The term tone is thus used in the technical sense of the function of pitch to distinguish words. Languages in which tone distinguishes meaning of words are called Tonal languages. More precisely, a tonal language “… is one in which an indication of pitch enters into the lexical realization of at least some morphemes.” (Yip, 2002).

Tones in English

English is a non-tone language, so it carries almost all the typical characteristics of this type. The tones of English language could be classified as “level, fall, rise, fall-rise and rise- fall” (Roach, 2003). The fall and rise-fall tones are used most frequently in English language. A report conducted on English tones showed that 66.1% of the tone units include a falling tone (Toivanen, 2003). British use falling tones mainly for statements, to express the meaning “that’s all, you don’t have to add more information” (fall) or indicate a bit reluctant agreement in their speech (rise-fall). As spreading through other countries, English have got a variety of accents. They have the typical characteristics of the original tone language, but because of the differences in regions, races, development history, etc., some significant changes have been made.

The tones of tonal languages are pitch patterns limited to individual syllables or words or relative pitch differences between one syllabic/word and the next. In Higgi language tones are just as important as consonants or vowels in distinguishing one word from another. In Higgi, like most other “tonal languages,” there are a small number of tone categories, just as there are fixed usually small number of vowels or consonants. The underlying, cross-dialectical logic of Higgi tone seems to involve a couple of such tone categories, many of which are (differently) merged in various dialects. Because tones are categories contrasting with each other, the actual sounds which correspond to them may vary from speaker to speaker, micro-dialect to micro-dialect, or style to style, so long as the contrasts remain intact.

Intonation

Intonation, in contrast, refers to pitch patterning imposed upon an utterance in order to express something other than differentiating words. Intonation responds to emotion, levels of politeness, and so on, or addresses such syntactic functions as showing a question. These functions are so important to most speech that in some everyday contexts the consonants and vowels can be largely lost and the intonation alone can carry the whole message. (That is probably the origin of the famous teenagers’ mumbling and grunting that so annoys non-teenagers.) Unlike tones, intonation is found in all spoken languages. Intonation is rarely directly taught in language classes, since most people consider it “natural” but there is of course variation from language to language, and differences in intonation can be responsible for a second-language speaker sounding unintentionally “abrupt,” “polite,” “uncertain” and so on. (For example, in American English “Hello, David” usually comes out with a loud Hello and a quiet David. In Mexican Spanish both words of Hola, David are equally loud or the David part is slightly louder.)

Intonation in English

Intonation in English refers to the ‘tune’ or ‘melody’ of the English language. Intonation is all about the tone and pitch of the voice and its modulation throughout the sentence. Changes in intonation can convey subtle information about the speaker’s attitude and emotions, in addition to indicating whether or not a sentence is a statement or question. Intonation in English can be used to convey the nature and mood of your sentence. Changes in intonation tell your listener if you have finished speaking or if you are going to add something else to the sentence. Intonation can also convey a friendly or unfriendly mood, sarcasm, humour, sadness, reluctance, excitement, anger, disapproval and many other attitudes and emotions.

Intonation and Contrast

Intonation is also used to convey contrast, such as in this sentence: ‘He might want to go dancing, but she absolutely hates it!’ The bold words are the stressed words.

The intonation in this instance would change to a very high pitch on the word ‘hates’. This indicates the strong contrast between what ‘he’ and ‘she’ want to do and the word ‘hates’ is stressed with strong intonation to show to the importance and magnitude of the negative emotion.

Intonation for Questions

There are two types of questions: open questions and closed questions. The type of intonation you use in your sentence depends on the type of question you are asking. Closed questions require a simple ‘yes’ or ‘no’ response, while open questions ask for new information and often require a longer response.

Intonation for closed questions

English intonation nearly always rises at the end of a sentence if it is a ‘closed’ (yes-no) question. For example:

‘Do you want a cup of tea with your cake’? Intonation and Mood in English

Intonation can convey the mood of the speaker. If the intonation of a sentence changes a lot this generally means the speaker has a high level of emotion about the subject of the sentence. In contrast, if the intonation is flat without much modulation, this generally means the speaker does not have strong emotions about the issue.

Rising Intonation

Rising intonation in English can be used to convey a variety of attitudes towards the listener or the topic of conversation. For example, rising intonation can convey friendliness and persuasiveness, while on the negative side it can also convey insecurity about a statement or a weaker conviction.

Falling Intonation

On the other hand, a falling intonation in English is used to convey security and confidence about a statement, along with a sense of finality or completion. However, falling intonation can also sound less friendly or even a little hostile, as though you are saying ‘this is the end of the matter, whether you agree or not’. Different types of intonation convey different moods and attitudes. Here are some examples of the same sentence with different moods indicated by a change of intonation:

‘When is the next train to London?’ – falling intonation (genuine question)

‘When is the next train to London?!’ – rising intonation (incredulous)

‘Where did you park the car’? – falling intonation (genuine question)

‘Where did you park the car?!’ rising intonation (incredulous)

Interactions: In tonal languages tone and intonation, involve pitch, and obviously interact. In musical lyrics, tone and intonation are both overridden by the melodic line, complicating understanding, often even for native speakers.

There are many languages of the world. Some are intonation languages while some others are tonal languages. Higgi and Chinese languages are grouped under the tone languages of the world. Higgi is a register tonal language while Chinese is a contour tonal language. They are languages in which the tones convey difference in meaning. Tone is a very important aspect of language especially tonal language like Higgi and Chinese. Phonology cannot be isolated from tone, as it has to do with speech sounds. Since tones are placed on syllables of words and syllables are being created out from tones of a particular word, they are bound together. Phonology is concerned with the exploitation of speech sounds to make meaningful construct. It is further expressed that one of the things done in phonology is to be able to identify the meaningful sounds used to convey semantic import. Consider the following Higgi data: /vă/ ‘a year’ /vá/ ‘rain’ /và/ ‘with’. The semantic implication of the lexical item is determined by the intonation in the pronunciation of the words. Phonetics according to Anagbogu, Mbah and Eme (2001) “Is that branch of language studies interested in studying the sounds used in language: how the speaker produces these sounds, how these sounds travel to the listener and how the listener eventually hears and understands the speaker”. As already mentioned, phonetics studies the mechanism for speech sound production; the characteristics; classification and accurate transcription of speech sounds through the air to the listeners; and the physiology of hearing.

Roach (2003) says: …there is no difference in meaning in such a clear cut way as in Mandarin Chinese, where, for example, mā means ‘mother’, má means ‘hemp’ and mă means ‘scold’, languages such as the above are called tone languages; although to most speakers of European languages they may seem strange and exotic, such languages are in fact spoken by a very large proportion of the world’s population called syllable. A syllable is usually made up of a consonant and vowel (CV), thus Yule (1996) says “A syllable must contain a vowel (or, vowel like) sound. The most common type of syllable in language also has a consonant before the vowel, often represented as CV”. All these tones fall in the proper way in order to give meaning to any word that is needed. The sound of these syllables in every word which is produced by the person pronouncing them is what is called “tone”. According to Anagbogu, Mbah and Eme (2001): A tone language is one which uses tone first to give meaning to a lexical item, which may otherwise appear similar in forms. Tone is seen as a feature realized on the syllables in tone languages. In languages such as the Higgi language in which tone operates, tone is usually realized on the vowel of the syllables or on any other element. When we say that tones differentiate two otherwise identical lexical items, we mean that although two words may be morphologically identical, the tonal

element can completely charge the meanings of these otherwise identical words. The role it plays is that it gives meaning to morphemes, words, phrases and sentences. Most times, one word, morpheme, phrase and sentence do have varieties of meaning. There are four different types of tones in Higgi language. They include: High tone, Low tone, down step, down drift. But those that are mostly seen in Higgi words include: high tone, low tone, down step.

Methodology

The study combined both perceptual and acoustic methods of analysis in this study. The sampling technique used is random sampling. The data for this study is gathered from the Dakwa dialect of the Higgi language of Michika local government area of Adamawa state. The Dakwa dialect is chosen because it is the most popular of the dialects of Higgi language. The dialect is spoken in Bazza district. The data for the study is presented using a word list that comprises of thirty (30) lexical items; however, only fifteen of the lexical items will be analyzed. Data is analyzed using the discursive method of data analysis. The analysis centers only on lexical level and how tone brings about a change in the meaning of words in Higgi language.

Data Presentation

The data is hereby presented in the word list form

|

xxiii. Plre

xxiv. Hala

xxv. Ghuma

xxvi. Nci

xxvii. Na

xxviii. Nbullu

xxix. Vua

xxx. Ltava

xxxi. Tsa

Data analysis

All languages use vowels and consonants in the representation of their words and a large number of languages are referred to as tonal languages. In this analysis focus is on three tonal pitches, the high, the low and the mid. The

analysis focuses only on how these tones affect meaning of the lexical items selected for the study. Below are the wordlist and the possible meaning of each of the words as it is affected by a rise, a fall, a fall/rise or a mid-tone.

The above when pronounced with a falling tone ‘Mà’ means ‘wrestling’. On the other hand, when pronounced with the rising tone ‘Má’ means

hunger. The distinction in the tone indicates that the same lexical item has two distinct meanings.

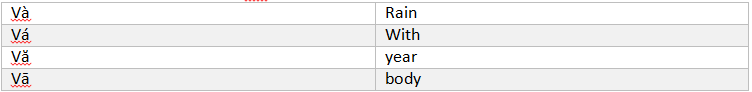

In the pronunciation of the ‘Va’ four distinct meanings are realized because of the variation in tones. ‘Và’ with the fall in the tone means ‘rain’. ‘Vá’ when pronounced with rise in the tone

means ‘with’. ‘Vă’ with falling and rising tone means a year. Lastly, ‘Vā’ with the mid-tone means human body.

The lexical item ‘Pla’ has two possible interpretations in Higgi language. ‘Plà’ pronounced with the falling tone means hand,

while if pronounced with a rise in the tone ‘Plá’ it means to untie or to loosen.

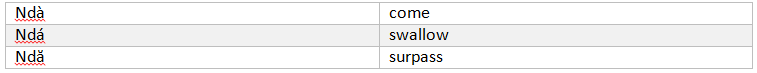

The first interpretation for the word ‘Nda’ is that when articulated with a falling tone ‘Ndà’ it means come. It is a beckon on someone to come close. The second meaning of ‘Ndá’ when the

tone is rising is to swallow either for or water. ‘Ndă’ has a third meaning because of the manner of articulation which is to surpass an individual or group in respect to performances.

The bird is referred to as ‘Eì’ when the word has a falling tone, while body cream, cooking oil or

any type of oil is referred to as ‘Eí’ when the tone of the word is rising.

The caste system is an integral part of the culture of the Higgi people. The caste has the freeborn and the outcast. The outcasts are termed as ‘Reghi’. ‘Mlà’ when pronounced with the falling

tone, means the freeborn. The second meaning is to repair any item that got spoilt. The tone rises in this articulation ‘Mlá’.

With the falling tone in the pronunciation of ‘Mblà’ it means a type of a snake, a cobra to be

precise. Similarly the word ‘Mblá’ when pronounced with the rising tone means run.

Three different meanings are derivable here due to change in tone. The first is ‘Pà’ because of the falling tone the word means to settle. The next

‘Pá’ which has a rising tone means to buy. The meaning due to falling/rising tone of the word ‘Pă’ is semblance.

The word ‘ntuà’ with the falling tone means death. When a person or an animal dies it is

referred to as ntuà. The farms are referred to as ‘Ntuá’. It is articulated with a rise in the tone.

The ear in Higgi language is ‘Ltmà’. The pronunciation the ear has the falling tone. Similarly, when the tone is rising as in ‘Ltmá’ the

meaning is to peel. The peeling could be that of groundnuts, Bambara nuts etc.

The lexical meaning for the word ‘Srà’ when pronounced with a falling tone is foot/leg. On the other hand ‘Srá’ when articulated with a rise

in the tone it has a completely different meaning which is the show of unpleasant attitude or some sort of naughtiness.

The word ‘lte’ has two different meanings as can be seen from the articulation of the word. When pronounced with a falling tone ‘Ltè’ means meat.

Any type of meat is referred to as ‘Ltè’. The same if pronounced with a rise in the tone ‘Lté’ means the name of a person, a place, or an animal.

In the pronunciation ‘Hyà’ which has the falling, the deducible meaning in Higgi language is sleep. Similarly, when ‘Hyá’ is pronounced with a fall in the tone, it means them. ‘Them’ is a third person personal pronoun plural.

If ‘Fwà’ is pronounced with a fall in the tone it is making a reference to a tree. In the same vein, if it is pronounced with a rise in the tone ‘Fwá’, it means a stagnant water or pond.

When one shoots something either with a stone or a gun it is ‘Hà’ is pronounced with a fall in the tone. The pot in which traditionally the Higgi people store water for drinking is called ‘Há’. The articulation is done with a rise in the tone. Lastly, there is a rise and fall tone in articulation of guinea corn which is ‘Hâ’.

Findings and conclusion

This paper has been able to look into the concept of Higgi tonal systems, importance of tone, types of tones, kinds of tones, rules that guide tones and rising and falling tone in Higgi language. The essence of this study is to bring to fore the tonal

patterns in Higgi language and this will go a long way to help students studying languages. Therefore, the researcher encourages learners of African languages to develop more interest in studying them. In proposing that tone be marked in a certain language, the boast is usually made of how a slight change in tone can effect a radical change in meaning, and therefore tone needs to be marked. The experiments show that tones in meaningful context can be readily identified by speakers of the language under review. Tones in isolated syllables, predictably, have lower recognition scores and are better identified by speakers of the same dialect than by speakers of others.

Reference

Akinlabi, A. and M. Liberman. 2000a. The tonal phonology of Yoruba Clitics. In Gerlach, B. And J. Grizenhout (eds) Clitics in phonology, morphology and syntax. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company,

Anagbogu, P. N., Mbah, M. B., Eme, C. A. (2001). Introduction to Linguistics. Awka: J. F. C. Gussenhoven, C. 2004. The phonology of tone and intonation. Cambridge University Press.

Peng, S-H. 1997. Production and perception of Taiwanese tones in different tonal and prosodic contexts.

Journal of Phonetics. 25: 371-400.

Pike, Eunice Victoria. 1948. Problems in Zapotec tone analysis. International Journal of American Linguistics 14.161-170. Reprinted in Ruth M. Brend (ed.), Studies in Tone and Intonation, 84-99. Basel: S. Karger

Blevins, J. (1993). A tonal analysis of Lithuanian nominal accent. Language 69, 237-273. Roach, P. (2003). English Phonetics and Phonology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Toivanen, J. (2003). Tone Choice in the English Intonation of Proficient Non-native Speakers. Retrieved December 27, 2014, from http://www.ling.umu.se/fonetik2003/

Yip, Moira (2002) Tone: Cambridge; Cambridge University

Yule, G. (1996). The Study of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Xu, Y. 1994 Production and perception of coarticulated tones. Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 95.4: 2240-2253.

0 Comments

ENGLISH: You are warmly invited to share your comments or ask questions regarding this post or related topics of interest. Your feedback serves as evidence of your appreciation for our hard work and ongoing efforts to sustain this extensive and informative blog. We value your input and engagement.

HAUSA: Kuna iya rubuto mana tsokaci ko tambayoyi a ƙasa. Tsokacinku game da abubuwan da muke ɗorawa shi zai tabbatar mana cewa mutane suna amfana da wannan ƙoƙari da muke yi na tattaro muku ɗimbin ilimummuka a wannan kafar intanet.