This article is published in the Tasambo Journal of Language, Literature, and Culture – Volume 1, Issue 1.

Musa Grema1

Saleh Jibir2

1 &2 Department of African Languages and Linguistics, Yobe State University, Damaturu, Yobe State, Nigeria

Abstract

The paper focuses on identifying and studying

those linguistic items borrowed from the Kanuri to Pabǝr/Bura language with special attention to the

modifications made to the vowels of the source language (Kanuri) before

incorporating the loanwords into the target language (Pabǝr/Bura). It is believed that in as much as two or

more communities with different linguistic backgrounds came in contact with one

another; there is a tendency that linguistic borrowing will take place.

Therefore, even though the languages under study belong to different language

phyla, there exists linguistic borrowing between them. Because of this, the

paper specifically focuses its attention on the adaptation of vowels in

borrowed words. The research can establish that the target language (Pabǝr/Bura) employed various phonological processes in

incorporating the loan words. More so vowel substitution is found to be the

major technique used by the target language in incorporating the borrowed

words. However, there are also cases of vowel deletion and insertion. The

research employed two distinct sources as methods of data collection. These

sources are primary and secondary. The primary source includes unobtrusive

observation when discourse is taking place in Pabǝr/Bura language and listening to Pabǝr/Bura radio program broadcast by Yobe

Broadcasting Corporation, Damaturu. Similarly, the researchers’ intuition plays

a significant role in identifying the loanwords. On the other hand, secondary

sources include written records, such as journal articles, dissertations, theses,

dictionaries, etc. The paper concludes that Pabǝr/Bura borrowed

a good number of lexical items from Kanuri, a Nilo-Saharan language.

Keywords:

Vowel, Kanuri, Pabǝr/Bura, adaptation, loan words, language

Introduction

Languages are

affected and influenced by other languages through contact. Language contacts

have been the focus of interest ever since philologists became aware of the

fact that no language would be free of foreign elements, and that languages

influence one another on a different levels. Such contact can have a variety of

linguistic influences or outcomes from one language to the other. In most cases,

it may result in borrowing (Dimanovski, (nd).

Communities interact

through trade, shared festivals and rituals, inter-marriages, and maybe wars in

some cases. Through all these, their languages change. They may come to sound

more similar, they may borrow some lexical items and forms from closed classes,

and even bound morphemes. The extent of the variation depends on numerous

social and cultural factors including the degrees of speakers’ knowledge of

each other’s languages, the domain in which different languages are used and

the type of language contact (Aikhenvald and Maitz 2021).

Greenberg

(1966) classifies Kanuri as one of the African languages which belong to the Nilo-Saharan

phylum. Interestingly, the word ‘Kanuri’ refers to both the language and the people.

Thus, the language is called Kanuri so also the speakers of the language. The

native speakers of Kanuri, a Saharan language, are largely found in the Borno

and Yobe states of Nigeria. But it is important to note that a good number of

them are also found in Bauchi, Jigawa, and Nasarawa states. It is also spoken

in the North-Eastern Republic of Niger, in towns like Zinder and Diffa,

Northern Cameroon, and Northern Chad. The major dialects of Kanuri are Yerwa

(standard form), Manga, Dagǝra, Bilma,

Koyam, and Suwurti (Bulakarima, 1997, 1999, 2001 and Schuh 2003).

Löhr, Wolff, & Awagana,

(2009, p, 166) are of the view that the Kanuri language is mainly spoken by

three (3) to four (4) million people in and around the speaking areas. Some of

these speakers use the language as a first or second language. Similarly, in

some communities in Borno and Yobe states, the Kanuri language is used as

lingua-franca.

Based on the historical account, the word Bura is used to

refer to the language, the land, and the people who inhabit Biu and its

environs. These areas include Kwaya-Kusar, Shani, Damboa, and Askira-Uba Local

Government Areas in Borno State and Gombi in Adamawa State, as well as some areas

in Gujba and Gulani Local Government Areas in Yobe State (Badejo, 1987;

Mohammed, Shettima, & Mu’azu, 2002). According to previous studies, Pabǝr/Bura is grouped under the Biu-Mandara

branch of Chadic languages of the Afro-Asiatic phylum along with Chibok,

Marghi, Pidlimdi, Tera, Jara, Kanakuru, Kombari, Higi and Kilba among others (Greenberg,

1966, and Newman, 1977). On the other hand, Ayuba

(2014) mentions that the estimated number of Bura speakers are seven hundred

thousand (700,000).

A lot of scholarly research were conducted on linguistic

borrowing and loanwords to be precise. These include Mohammed, (1987),

Dikwa, (1988, 2006), Baldi, (1992, 1995, 2001), Yalwa, (1992), Bulakarima, (1999),

Abdullahi, (2008), Sani, (2009, 2011), Shettima, & Abdullahi, (2010),

Kukuri, & Grema, (2013), Zubairu, (2013), Bukar, (2014), Kaka, (2015),

Grema, (2017, 2018) and host of others. However, to the best of our knowledge and ability, none of

the previous research works on the adaptation of Kanuri loans in Pabər /Bura. Based on this notion, it is believed that there is a

gap that needs to be closed by the present research work. Because of this, the

present research work is aimed at identifying those linguistic item(s) borrowed

into Pabər/Bura from

Kanuri. It will also study those items linguistically to examine their

phonological modifications in the target language, and the reason for such

modifications is for the loanwords to behave like native words of the target

language. The research is, therefore, expected to contribute to the area of

linguistic borrowing.

Literature Review

As already

mentioned above there are a lot of works on linguistic borrowing. Given

this, in this part of the

paper, related literature review is provided for

better understanding. Let’s

begin with Bulakarima (1999) who defines loan words as those linguistic

elements which originally borrowed from one language and finally incorporated

into another language. He goes further to state that such linguistic elements

can be borrowed either directly or indirectly. He stresses that the form might

be adapted to suit the phonological and morphological systems of the target

language. However, it is likely that the loan items can or cannot retain the

meaning of the original language he successfully succeeded in identifying and

analyzing the Kanuri loanwords in Guddiranci.

On the other hand, Dikwa (2006) works on loanwords in Kanuri where he

chronologically arranged the donor languages into Kanuri as Arabic, English,

French, and Hausa. Arabic became first because of the early intimate contact

with the Kanuri people. He is of the view that some of the Arabic

loanwords in Kanuri require only a slight adaptation to be incorporated in

Kanuri due to their nature and the lengthy duration of their usage by Kanuri

people. As a result, they differ only slightly from their source. Shettima & Abdullahi (2010) observe that all Arabic

and English loanwords in Kanuri must satisfy the Kanuri basic syllabic

structure of CV and CVC and all onset and codas of the loanwords must have

epenthetic vowels, except for those codas with sonorant or sibilant. Another

issue raised is the insertion of an epenthetic vowel after the nasal cluster in

the coda of the loanword.

However

Shettima & Abdullahi (2010) went further to assert that not only syllabic

structures change but appended vowels also behave systematically and they are

predictable, adding that after the vowels /a/,

/i/, and /e/, the appended vowel is /i/. The conditioning factor of the word-final

/ǝ/ is vowel /a/ followed by an obstruent. In

most cases, the vowel /u/ is preferred after labials and, in the case of Arabic

loans in the syllable-final clusters, vowel harmony is employed by copying the

adjacent one. They also observe that there are instances where Kanuri deletes

extra syllabic vowels in its attempt to integrate loanwords. They provide

examples to buttress all the issues they raised in the paper.

More

so Kukuri and Grema (2013) center their attention on the phonological

adaptation of Kanuri loanwords in Hausa. In their attempt to study those Kanuri

words loaned into Hausa, they identify various processes that are involved in

the course of the adaptation. According to them some sounds (consonants and

vowels) are replaced with nearest equivalents in the target language. To

justify this claim, they cite some examples such as gàltimà

˃ gàlààdiimàà

(a traditional title), zarmà ˃ jarmà

(a traditional title), maîràm

˃ mairàn

(princess), kәskarí

˃ kiskaadii

(outskirt Qur’anic recitation), bәlàmà ˃ bulààmà

(ward head) and kәlisà

˃ kiliisàà

(gallop).

Bukar (2014) is another work worth reviewing. He focuses his

attention on the structural modification of Hausa loanwords in Babur-Bura. He

examines the phonological and morphological behaviours of the Hausa words

loaned into Babur-Bura. He identifies various phonological processes that are

involved in the course of modifying the Hausa words before they are fully

integrated into Babur-Bura. These processes are sound substitution,

glottalization, deglottalization, palatalization, voicing, segment insertion,

deletion of article at the initial position, and deletion of segments

at the medial and final positions. In the case of vowel substitution Bukar (2014) observes two forms of

such substitution. The Hausa vowel /i/ becomes /ә/ in the loanwords and /u/ changes to /ә/ in the target language. He cites some examples such as, [bireedì]

> [bәreedì], ‘bread’, [bindígàa] > [bәndәgùu], ‘gun’, [bookìtì] > [boogәdì], ‘bucket’, [burgàa] > [bәrgàa], ‘bragging’, [burjìi] > [bәrjìi], ‘feeder road’ and [dubuu] > [dәvuu], ‘thousand’.

These are some of the previous works which are

related to the present research. However, apart from these, there is a host of

other research on linguistic borrowing and loanwords adaptation adoption to be

precise.

Methodology and Theoretical Framework

This

research employed two techniques as sources for data collection. These

techniques are primary and secondary sources. The primary source includes

unobtrusive observation and listening to Pabǝr/Bura and

Kanuri Radio programmes broadcast by Yobe Broadcasting Corporation (YBC) while

the secondary sources include written records such as dictionaries, journal

articles, dissertations, theses, etc. The

researchers take ample time and listen to two Pabǝr/Bura

radio programmes; namely Sakar Vukci (discussions between the guests or artists

on any chosen issue) and Sakar Thawarsi Akwa Pabǝr/Bura

(Request in Pabǝr/Bura language) which

is broadcast by the state own AM/FM radio stations in Damaturu.

The

theoretical framework employed by this research article is Generative

Phonology. This framework is credited to Chomsky and Halle (1968) and it is

considered a sub-field of the general study of language known as Generative

Grammar. In Generative Phonology, phonological components are analyzed using a sequence

of phonological rules to produce surface forms. Therefore, it is a subfield that

is mainly concerned with the analysis of the continuum of speech into distinct

segments to establish a series of universal rules for relating the output of

the syntactic component of generative grammar to its surface form. Because of

this, all the examples cited in this research work are accompanied by a

phonological rule to account for the phenomenon.

Data Presentation and Analysis

The data is presented here and the analysis focuses mainly

on phonological adaptations, the lexical items are classified based on the phonological

process involved in incorporating the loanword and each is analyzed separately.

Two representations are used namely phonetic and orthographic representations

for each language while the translation of each of the lexical items is

provided to serve as gloss.

Vowel Adaptation

The concept of adaptation is derived from the verb ‘adapt’,

therefore the term refers to a situation where a linguistic element undergoes

some modification processes before it becomes accepted in the target language.

Thus, the original form of the source language is altered to suit into the

phonological or morphological patterns of the target language (Aktürk-Drake,

2015, p. 18). On the hand, a vowel is seen by Trask (1997, p. 235)

phonetically as “speech sounds whose production involves no significant

obstruction of the airstream” and, phonologically, as “a segment of high

sonority which occupies the nucleus of a syllable.” Similarly, in the words of

Sani (2005, p. 20) phonetically, a vowel is “… a speech sound whose

articulation does not involve obstruction of air-flow, but essentially

vibration of the vocal cords.” Having said that, this section of the research

work will look at the modifications experienced by loanwords that involve

vowels alone in the process of integrating it in the target language.

Vowel Substitution

It is noticed that

vowel substitution is one of the strategies employed by the target language

(Pabər/Bura) in

integrating the Kanuri loanwords. In this case, some vowels in the source

language are substituted with another vowel in the target language. This

substitution process involves /ǝ/→

/u/, /ǝ/ → /a/, /a/ → /ǝ/, /a/ → /e/, /ǝ/ → /u/, /e/ → /i/ and /ǝ/ →/i/.

Let us begin with a situation where a mid, central,

unrounded vowel /ǝ/ is substituted with a high, back, rounded vowel /u/ in the

process of integrating the loanwords. Consider the following examples:

Example 1:

|

|

Kanuri |

Pabər/Bura |

|

||

|

|

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Gloss |

|

a. |

[bəʤì] |

bəji |

[bùʤí] |

buji |

mat |

|

b. |

[bə՝ndə՝r] |

bəndər |

[bùndír] |

bundir |

manure |

|

c. |

[kámbígə`] |

kambigə |

[kámbígù] |

kambigu |

argue |

|

d. |

[kwúŋgənà] |

kungəna |

[kwúŋgwùnà] |

kunguna |

money |

|

e. |

[kwùtəràm] |

kutəram |

[kwùtùràm] |

kuturam |

mirror |

|

f. |

[mágə՝] |

magə |

[mágwù] |

magu |

week |

|

g. |

[zəmbələm] |

zəmbələm |

[zùmbùlùm] |

zumbulum |

uncircumcised |

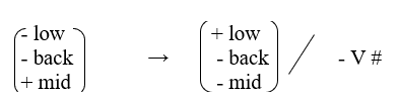

Considering the above example 1, it is established

that a vowel in the source language with feature specification [-high], [-back]

is substituted with another vowel in the target language with feature

specification [+high], [+back] in the target language. It is interesting to

mention that this phenomenon takes place in both open and closed syllable except

for example 1b where the vowel concerned is also substituted with a high,

front, unrounded vowel in the second syllable which will be discussed later. Using

distinctive feature values, this phenomenon can be represented in the following

rule.

Rule 1:

In the same vein, it is also noted that

a mid, central, unrounded vowel /ǝ/ in the original form is substituted with a low, central,

unrounded vowel /a/ when fully integrated in the target language. Let us

consider the following examples:

Example 2:

|

|

Kanuri |

Pabər/Bura |

|

||

|

|

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Gloss |

|

a |

[sártə] |

sartə |

[sártá] |

sarta |

deadline |

|

b |

[bàdìtə] |

baditə |

[bàxìtá] |

baxita |

begin

|

|

c |

[fàràktə] |

faraktə |

[pàràktá] |

parakta |

widen

|

|

d |

[kàlàktə] |

kalaktə |

[kàlàktá] |

kalakta |

return

|

|

e |

[kàrə`ngə`] |

karəngə |

[kàràngà] |

karanga

|

near |

|

f |

[álàgtə՝] |

alagə |

[álàgtà] |

alagta |

nature |

Looking at the above example 2, it also

established that in the process of integrating the Kanuri words into Pabər/Bura another form of vowel substitution is noticed. A

vowel with feature specification [- low], [- back] in the original form of the

source language is substituted with another vowel with feature specification [+

low], [- back] in the target language. It is important at this juncture to

mention that all the substitutions take place at the word-final position as can

be seen in example 2a – f respectably. This phonological phenomenon is

represented in the below rule.

Rule 2:

Another plausible evidence of vowel

substitution in the process of integrating Kanuri loans in Pabər/Bura is a situation where a low, central vowel /a/ in the

original form of the word in the source language is substituted with a mid,

central vowel /ǝ/ in the target language. Consider the following example;

Example 3:

|

|

Kanuri |

Pabər/Bura |

|

||

|

|

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Gloss |

|

a. |

[kàká] |

kaka |

[k՝əgá] |

kəga |

grand parent |

In this case also, one can notice that a vowel with feature specification [+ low], [- back] in the original form of the word in the source language is substituted with a vowel with feature specification [- low], [- back] in the target language unlike what appears in example 2a-f above. In this case, the substitution takes place between two consonants. The following rule represents the phenomenon.

Rule 3:

More so, another vowel substitution that

is evident based on the data collected for the research is a situation where a

mid, back, rounded vowel in the source language is substituted with a low,

central, unrounded vowel in the target language. This is justified in the

following example.

Example 4:

|

|

Kanuri |

Pabər/Bura |

|

||

|

|

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Gloss |

|

a. |

[zówàr] |

zowar |

[záwàr] |

zawar |

divorced woman |

|

b. |

[kóró] |

koro |

[kórà] |

kora |

donkey |

|

c. |

[gwórò] |

gworo |

[gwárà] |

gwara |

kolanut |

|

d. |

[zòlì] |

zoli |

[zwàlì] |

zwali |

stupid |

|

e. |

[kótómí] |

kotomi |

[kwátámí] |

kwatami |

gutter |

|

f. |

[bòrkó] |

borko |

[bàrgó] |

shakwara |

blanket |

|

g. |

[shókórá] |

shokora |

[shákwárá] |

shakwara |

gawun |

In the above examples, one can see that

a vowel with feature specification [+ back] [+ round] [– high] in the source

language is substituted with another vowel with feature specification [– back]

[– round] [– high] in between two consonants or before a vowel at the end of a

word. Using distinctive feature values let us provide a phonological rule to

account for the substitution that takes place below.

Rule 4:

Additional plausible evidence of vowel substitution found to

occur in the process of integrating Kanuri loanwords in Pabǝr/Bura is a situation where a mid,

central vowel in the original form of the word is substituted with a high,

front vowel in the target language. This phenomenon occurred in two distinct

phonological environments namely before a consonant at the end of a word as in

example (5a – c) and in between two consonants which can be seen in example (5d

and e). Consider the following examples:

Example 5:

|

|

Kanuri |

Pabər/Bura |

|

||

|

|

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Gloss |

|

a. |

[ŋgwùtə] |

ngutə |

[ŋgwùxì] |

nguxi |

bow

down |

|

b. |

[làrdə] |

lardə |

[làrdì] |

lardi |

country |

|

c. |

[ŋgùdə] |

ngudə |

[ŋgùdì] |

ngudi |

poor |

|

d. |

[təmàjì] |

təmaji |

[tìmàjì] |

timaji |

fiancé |

|

e. |

[bə`ndə`r] |

bəndər |

[bùndìr] |

bundir |

manure |

In the

above examples, it is clear that in the process of integrating the Kanuri loans

in Pabǝr/Bura

vowel substitution takes place. This is because a vowel with feature

specification [ – high] [+ mid] [– pal] in the original form is substituted with

another vowel with feature specification [+ high] [– mid] [+ pal] before it is

fully incorporated in the target language. Let’s formulate a phonological rule

to account for the said phenomenon.

Rule 5:

Vowel Deletion

Furthermore, vowel deletion is another

phonological process employed by the target language (Pabər/Bura) in

integrating the Kanuri loanword. In this case, it is noticed that there is a

situation where a vowel in the original form of the source language is

completely deleted in the target language before it is fully integrated. A

situation where a mid, central, unrounded vowel is completely deleted word

medially is noticed. Consider the following examples.

Example 6:

|

|

Kanuri |

Pabər/Bura |

|

||

|

|

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Gloss |

|

a. |

[sàntəràm] |

santəram |

[sàndràm] |

sandram |

antimony |

|

b. |

[shìtə՝rà] |

shitəra |

[shìdrà] |

shidra |

funeral |

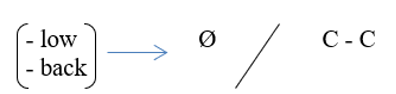

In the above example, it is established

that a vowel with feature specification [- low], [- back] is a completely

deleted word medially in the process of integrating the Kanuri loans in Pabər/Bura. Using the

distinctive feature values this phenomenon is represented in the below rule.

Rule 6:

Vowel Insertion

Another phonological process employed

by the target language in incorporating the Kanuri loans is vowel insertion.

Vowel insertion is a phonological process where an additional vowel is inserted

into a particular word. In the case of Kanuri loans in Pabər/Bura, two instances

are noticed. Firstly, a situation where there is the insertion of a low,

central, unrounded vowel /a/ and secondly where a high, front, unrounded vowel

/i/ is inserted as in examples (7a and 7b-c). Interestingly all the phenomenon

takes place at word final positions. Let’s consider the following example.

Example 7:

|

|

Kanuri |

Pabər/Bura |

|

||

|

|

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Phonetic |

Orthography |

Gloss |

|

a. |

[ŋgâl] |

ngal |

[ŋgâlá] |

ngala |

measure |

|

b. |

[ʤángàl] |

jangal |

[ʤáŋgàlì] |

jangali |

livestock tax |

|

c. |

[fásàl] |

fasal |

[pásàlì] |

pasali |

plan |

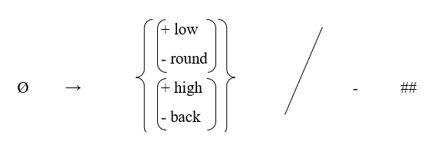

In the above example, it is evidence that there is a case of vowel insertion in the process of integrating the Kanuri loans in Pabər/Bura. In example (7a), a vowel with feature specification [+ low], [- round] is inserted word finally before the loan is fully incorporated. In the same vein, in example (7b - c), a vowel with feature specification [+ high], [- back] is also inserted word finally in the process of integrating the loanword. Let’s consider the below phonological rule in that respect.

Rule 7:

Conclusion

The paper attempted to study the vowel

adaptation of Kanuri loanwords in Pabǝr/Bura. It is clear from

the aforementioned discussions that vowel substitution, vowel deletion, and

vowel insertion are found to be paramount in the process of incorporating the

Kanuri loanwords in Pabǝr/Bura. In the substitution

process, the paper noticed that there are cases of vowel raising and vowel

lowering. The paper also succeeded in providing phonological rules per

generative phonology to account for all the processes involved in integrating

the Kanuri loans in Pabǝr/Bura. This justified

that, the research employed Generative phonology as its theoretical framework.

It is also clear that the research sought its data from two different sources;

namely primary and secondary. The paper concludes that Kanuri and Pabǝr/Bura being neigbours for a long time, pave a way for linguistic

borrowing to take place. Thus, Pabǝr/Bura borrowed some

lexical items from the Kanuri language as clearly shown in the paper.

References

1. Abdullahi,

S. A. (2008). Loanwords in Kanuri newspapers: A descriptive analysis.

[Unpublished Ph.D.Thesis]. Department of Languages and Linguistics: University

of Maiduguri, Maiduguri.

2.

Aktürk-Drake,

M. (2015). Phonological adoption through bilingual borrowing comparing elite

bilinguals and heritage bilinguals [Unpublished Phd Thesis]. Centre for

Research on Bilingualism Department of Swedish Language and Multilingualism

Stockholm University.

3. Ayuba, Y.M (2014). The

Story of the Origins of the Bura/Pabir People of NORTHEAST Nigeria.

Bloomington: Authorhouse LLC.

4. Badejo, B. R. & Bura Orthography Committee (1987). Bura Language

Orthography.

a.

Orthographies of Nigerian Languages, Manual v, National Language Centre.

5. Baldi, S. (1992). Arabic Loanwords in Hausa via Kanuri and

Fulfulde. In Ebermann, Erwin

& Sommerauer, Erich R. & Thomanek, Karl E. (eds.), Komparative

Afrikanistik (Festschrift

Mukarovsky), 9–14.

6. Baldi, S. (1995). On Arabic Loans in Hausa and Kanuri. In

Ibriszimow, Dymitr &Leger, Rudolf (eds.), Studia Chadica et

Hamito-Semitica: Akten des Internationalen Symposions zur Tschadsprachenforschung, 252–278.

7. Baldi, S.

N. (2001). ‘On Arabic Loans in Yoruba’, in Festschrift Für Hermann

Jungraithmayr. Köln: Rüdiger Koppe Verlag. 253-278

8. Bukar, M.

M. (2014). An Examination of structural modification of Hausa Loanwords in

Babur-Bura. [Unpublished M. A. dissertation]. Department of Languages and

Linguistics, University of Maiduguri.

9. Bulakarima, S. U. (1997). Survey of Kanuri Dialcets.

In Cyffer, N. and Geider, T. (eds) Advances in Kanuri Scholarship. Rüdiger Koppe Verlag.

10. Bulakarima, S. U. (1999). Kanuri Loanwords in Guddiranci. MAJOLLS: Maiduguri

Journal of Linguistic and Literary Studies Vol 1.

61-70

11. Bulakarima, S. U.

(2001). A study in Kanuri Dialectology:

Phonological and Dialectal Distribution in Mowar. Awwal Printing &

Publications.

12. Bussmann,

H. (2006). Routledge Dictionary of Language

and Linguistics. Gregory, T. and Kerstin, K. (Trns. & Eds). Taylor

& Francis.

13. Chomsky,

N. & Halle, M. (1968). The Sound Pattern

of English. Harper & Row Publishers.

14. Dikwa, K.

A. (1988). Arabic Loanwords in Kanuri. [Unpublished M. A. Thesis]. Department

of Languages and Linguistics: University of Maiduguri.

15. Dikwa, K.

A. (2006). Loanwords in Kanuri. [Unpublished Ph. D. Thesis]. Department of

Languages and Linguistics: University of Maiduguri.

16. Dimanovski, V. M. (nd).

Linguistic Anthropology- Language in Contact.

Institute of

17. Linguistics, Faculty

of Philosophy, University of Zagreb.

18. Greenberg,

J. H. (1966). Languages of Africa. The Hague, Mouton.

19. Grema, M,

(2018). Linguistic Borrowing: A study of Hausa Loanwords in Kanuri. [Phd

Thesis]. Department of Nigerian Languages, Bayero University, Kano

20. Grema, M.

(2017). Vowel Laxing as a Technique in Hausa Words Loaned into Kanuri. Yobe Journal of Language, Literature and

Culture Vol. 5, 97-100.

21. Kaka, A.

K. (2015). A Descriptive Study of Phonological Substitution of Loanwords in the

Dictionary: Kalmaram Təlamyindia Kanori Faransa-a.

[Unpublished M.A. Dissertation]. Department of Languages and Linguistics,

University of Maiduguri.

22. Kukuri, M.

M. and Grema, M. (2013). Linguistic Borrowing: Phonological Adaptation of

Kanuri Loanwords in Hausa. In Yalwa, L. D. et al (eds) Studies in Hausa Language, Literature and Culture The 1st

National Conference. PP 150-157

23. Löhr, D., Wolff, H. E. &

Awagana, A. (2008). Loanwords in Kanuri, a Saharan Language. In M. Haspelmath (ed.) World’s

languages a comparative handbook. De Gruyter. pp. 166-190

24. Mohammed,

A. B. (1987). A Linguistic Study of the Nativisation of English Loanwords in

Gombe Fulfulde. [Unpublished Ph.D. Thesis]. Bayero University, Kano.

25. Mohammed, S. Shettima, A. K. and Mua’zu M. A. (2002).

Assimilation Processes in Bura. Mojolls

1V (1) Department of Languages and Linguistics University of Maiduguri pp.

61-70.

26. Newman, P. (1977). Chadic Classification and Reconstruction.

Afro-asiatic Linguistics, 5 (1):1-

42.

27.

Aikhenvald, A. Y. & Maitz P. (2021). Language

Contact and Language Change in Multilingual Context. Ilalian Journal of

Linguistics [Online Available at: Doi:10.26346/1120-2726.168.

28. Sani, M.

A. Z. (2005). An Introductory Phonology

of Hausa (with exercises). Benchmark Publishers.

29. Sani, M.

A. Z. (2009). A Look at Palatalyzing Tendencies of an Arresting /i/ in English

and Arabic Loanwords in Hausa. In Sergio Baldi and Hafizu Miko Yakasai (eds.) Proceedings of the 2nd

International Conference on Hausa Studies: African Perspectives, Bayero

University, Kano.

30. Sani, M.

A. Z. (2011). Tone Placement and Stress Replacement in English and Arabic Loanwords

in Hausa. Studies in Hausa Language,

Literature and Culture. Sixth International Conference. C.S.N.L. Bayero

University, Kano.

31. Schuh, R.

G. (2003). The linguistic Influence of Kanuri on Bade and Ngizim. MAJOLLS: Maiduguri Journal of Linguistics and Literary Studies Vol

V.

32. Shettima,

A. K. and Abdullahi, S. A. (2010). Vowel Epenthesis in Kanuri Loanwords. FAIS Journal of Humanities Vol. 4 No 1.

33. Trask, R.

L. (1997). A Student’s Dictionary of Language

and Linguistics. Arnold, Hodder Headline Group.

34. Yalwa, L.

D. (1992). Arabic Loanwords in Hausa.

Journal of the African Activist

Association Vol. XX No III Special Issues on Afro-Arab. 101-131

35. Zubairu,

H. (2013). Phonological Study of Hausa and Yoruba Loanwords. In Munkaila, M. and

Zulyadaini, B. (eds) Language, Literature

and Culture Festschrift in Honour of Professor Abdulhamid Abubakar. Ahmadu

Bello University Press.

DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.36349/tjllc.2022.v01i01.001

0 Comments

ENGLISH: You are warmly invited to share your comments or ask questions regarding this post or related topics of interest. Your feedback serves as evidence of your appreciation for our hard work and ongoing efforts to sustain this extensive and informative blog. We value your input and engagement.

HAUSA: Kuna iya rubuto mana tsokaci ko tambayoyi a ƙasa. Tsokacinku game da abubuwan da muke ɗorawa shi zai tabbatar mana cewa mutane suna amfana da wannan ƙoƙari da muke yi na tattaro muku ɗimbin ilimummuka a wannan kafar intanet.