ABSTRACT: The Bayajidda legend/history/myth/ as is obtainable amongst the

Hausa people of sub-Saharan Africa and its study as a total or some portion of

the Hausa people’s history and identity is an amazing intellectual task. It

borders on almost all facets of knowledge; historiography, historicism,

cultural geography, myth, religion, politics, war, migrations, states and

statelessness, the rise and fall of empires and kingdoms, linguistic studies.

Researchers are still at it. It is that complex. Many historical, archival,

archeological researches and literatures; most especially by the colonialists

and their agents, as well as ‘local’ scholars; and extant chronicles; abound in

our understanding of the phenomenon of ‘out of Africa’ theory as it impacts on

the Hausa people and their identity. Consequently, subjecting the area to

genetic/genographic test is now paramount as stop gab in research. A genetic

data collected from the area and analyzed by geneticists in the light of

current genographic templates may give us a glimpse on the origin, migration

patterns of the people as well as the pre-history and the major landmarks

followed by the sub-Saharan African community from the earliest times. The

paper will attempt to follow the footprints of the Hausa community from as

earlier as 60,000 years back to about 5,600 – 9,200 years ago when the Hausa

communities’ ancestors lived in West Asia and later settled in their cotemporary homes. Geneticists have

painstakingly gone through the genetic samples supplied and by looking at the

order in which these markers occurred over time, have constructed the

breadcrumbs and traced the journey of Hausa ancestors across the globe and

their various identities and manifestations. Furthermore, with these

markers; geneticists have created a human family tree of the Hausa people. This

is achieved because everyone alive today falls on a particular branch of this

tree. Scientists have also examined the data from the markers to determine

which branch Hausa people belong to. The result of that analysis; Hausa people

personal journey and the identities they merged into as well as their current

cultural transformation is what would be outlined in this paper.

Keywords: History, literary history, geography, genetics and Genography

HUMAN JOURNEY AND HUMAN ORIGIN: ON THE FOOTPRINTS OF HAUSA PEOPLE

Ibrahim A.M. Malumfashi

Department of Nigerian Languages and

Linguistics

Kaduna State University, Kaduna

Email: malumfashi@kasu.edu.ng

Introduction

If not for the intervention of modern and/or western approaches in

African studies as Dierk Lange asserted in his summary of years of painstaking

academic research, field work and extant study of ancient manuscripts

concerning the historical inquiry in African societies, most of our knowledge

in the field of Hausa origin would have been confronted with missing links or

gaps and untypical. Very little is known about the pre-Christian and Islamic

tendencies amongst most Hausa city states, that information already in the

limelight were underreported or willfully ignored. The scrutiny of ‘unexplored written,

oral and cult-mythological sources’ outlined a semblance of a historical

reconstruction of the administrative set ups of Sudanese states of sub-Saharan

Africa, Lange (2004c). Consequently, Lange (2004c) corpus is a fuller new light

that encapsulate the interrelatedness of the ‘Canaanite-Israelite cultural

pattern in specific African societies,’ from where ‘important new insights for

the understanding of Semitic myth and ritual features can be derived from

existing African situations,’ most especially Hausa city states.

This same or similar method is adopted by Last (2004) on the

positioning of Arabic and oral sources as alternatives in understanding the

historical milieu of the organizational structure of the ancient Hausa states.

In the absence of archaeological evidence of the settlements of Hausa people he

avers, we have still to rely, unfortunately, wholly on the evidence in the

Arabic sources and on oral traditions. ‘Further scrutiny may show that the data

in those sources are accurate only in the sense that the people who first

recorded the data understood exactly what they meant. The task, then, is to

understand their “mental maps", the framework in which the information

made good sense to them. It does not matter if one peoples’ mental map differs

from another's: for there is, at least in this world, no History, only

histories.’

From these two extremes but related ideals we situate the

intellectual engagements as regards the history of Hausa states of sub-Saharan

Africa and the Bayajidda legend. Horrendous efforts are on ground by many

scholars that dissected the field; see for instance Infakul Maisuri of Muhammad Bello, Muhammad and Boyd, (1974),

Palmer, (1928), Adamu, (1978), Usman, (1981), Smith, (1987), Last, (1984), Lange,

(2004c), Adamu, (2011), Adamu, (1997), Malumfashi, (2018) and extant chronicles

of Kano, Abuja and Daura. Other studies by Dierk Lange by far have dusted the

field, (see for instance Lange (2012, 2013, 2018, 2019,). These are but textual

documentations and analyses, we need to go beyond paper ad pen and embraced

science as we are neck deep in the 21st century, which is an age

where some semblance of exactness is required in researches and studies; this

is where genetics and Genography comes in handy.

An Overview of Hausa People’s History, Legends and the Efficacy of Genography

The story and/or history of ancient people as geneticists have

testified is buried in many facets of life, only few are and/or can be unearthed

through historiographical studies, archeological excavations, cultural testimonies,

oral traditions, and such others as left behind for inheritors.

Just like other humans scattered around the world; the history of

Hausa people’s’ immediate and far-fetched descendants is shrouded in such kind of complex

rigmarole. Enthusiasm of the past that can be found through many (oral) histories of Hausa people and city

states, and few written sources available, nothing in them shows Hausa people

were here in Northern Nigeria, 300 years ago.

This can be glimpsed from many historical studies of origin; for instance,

from the oral and some documented sources I traced back my origin to

Katsina/Daura axis (in preset Katsina state) about 230 years ago and my original

linguistic conglomeration was Fulfulde, not Hausa and my great-grandfathers came to Hausa land from the ‘east’

with their cattle and books, towed along, (Malumfashi, 2017). The same scenario is found

from my mother’s side, my ancestors traversed an expense of land around

Bichi to Karaduwa and Malumfashi in present day Katsina and Kano States; my

great-grandfathers came from the ‘east’ also, with hordes of cattle and books

to meet the Shehu Usmanu Danfodiyo and his ilk preparing for the Jihad around 1805, (Malumfashi,

2017). Consequently, the Hausa people, are then an admixture of Fulani and

Hausa origin; as many of their great-grand fathers were basically Fulani

acculturated and linguistically assimilated into Hausa, later in life.

If that is the case, where were my great-grand fathers before then?

What was the language they communicated with before here (in Northern Nigeria)

and there (in Daura, Katsina, Bichi, Karadua) and before there and even further

there (way back in the ‘east)?

These and may of such questions and interceptive queries cannot be

simplified by history, archeology or myths and legends of the people, alone,

but can partly be revealed by some aspects of scientific inquiry through the “record of ancient human migrations in the

DNA of living people.” This is established as "every drop of human blood contains a

history book written in the language of our genes," Shreeve,

(2006).

Literary historians on the other hand have to go cap in hand to

genetics to unravel some of these issues. Science being a replica of an exact

methodological investigation, one can’t help but agree that since we are ONE

WORLD and ONE PEOPLE, as captured by Spencer Wells of the Genographic Project, (https://youtu.be/a-YKAaky7s),

we can then trace Hausa peoples’ remotest origin and language from these

perspectives.

There was once one human race, one

language; then so many other human races and so many other languages evolved

over time. They evolved from the same source. The same Proto language evolved

over time is the same progeny of modern languages today, with thousand

mutations. Science has since come into the fold to account for some of these

differences, but in as much as science is vital in this search for origins,

genetics can only account for some portions of the present permutations to

account for how and why of our present acculturation.

Researches have indicated the

possibility/probability of the existence of modern man about 175,000 years ago,

(https://youtu.be/a-YKAaky7s),

when modern man came face to face with pre-historic

man, scientists until today cannot locate the compass and whether they

intermingled. In the time past many races and languages found themselves in one

location or the other, and through journeys and migrations humans settled and

populate the world as we see it today, among which are the Hausa people.

In trying to gauge the intermingling and peopling of the world, a

lot of efforts have been exerted on the possibility of finding the commencement

and the nature of the journey to establish the present location of the Hausa

people. What is obtainable is a lot of conjectures and combination of sources.

Sometimes there is clear cut confusion, because people are talking about TWO

distinct issues, HAUSAWA (the People) and HAUSA (the language), both divergent

at the same time related.

To our understanding, the people were/are/will be, around forever.

Language on the other hand is an amalgam of so many things. It was Hausa now,

what was it 175,000 years ago? Or to come near us, what was it 20,000 years

ago? Or just recent, were there Hausa people or language 700 years ago? There

were the people of course, but no language! What then was the language of the

people called?

It is now more evident that subjecting the Hausa people and history

to the full test of genetic science is now paramount. In between March 2016 ad

December 2017 the current researchers was at the USA where he spends 10 days

during which a comprehensive analysis to identify thousands of genetic

markers—breadcrumbs—in his DNA, was undertaken as a first step towards

understanding the ancestry of the Hausa people, (Malumfashi, 2017). Subsequently, another kit was supplied and

analysis done on the sample by the Genographic

Project Laboratory based in Washington DC. The Result came out, detailed

and comprehensive on both sides; paternal and maternal.

By looking at the order in which these markers as extracted occurred

from these samples, geneticists follow the breadcrumbs and trace the journey of

Hausa people’s ancestors across the globe. Furthermore, with these

markers’ geneticists create a human family tree of the Hausa people. They

examine the data from the markers to determine which branch Hausa people belong

to. The results of that analysis-Hausa ancestral personal journey or the Hausa

people personal journey is outlined; Malumfashi (2017, 2018).

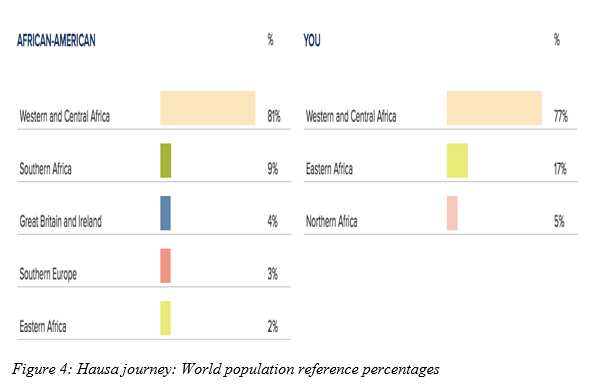

To get a glimpse of Hausa ancestry; the DNA results is compared with

the reference populations currently available on the database of Genographic

Project. An estimate is made to determine which of these populations were most

similar to Hausas in terms of the genetic markers the data submitted carry,

Malumfashi (2018).

We are already aware from other researches of this kind, Hausa

people are not what they are or what others see today, as ‘we are all more than

the sum of our parts,’ Malumfashi (2017). Expectedly, the research shows the

Hausa people affiliations with a set of eighteen world regions. We see Hausa

peoples’ information, going back six generations. That picture gives us an

understanding in percentages that reflect both recent influences and ancient

genetic patterns in Hausa peoples’ DNA. The result finally shows Hausa people

migrated to and from different regions, mixing for hundreds or even thousands

of years, Malumfashi (2018).

Genography and History: On the Footprints of the Hausa People

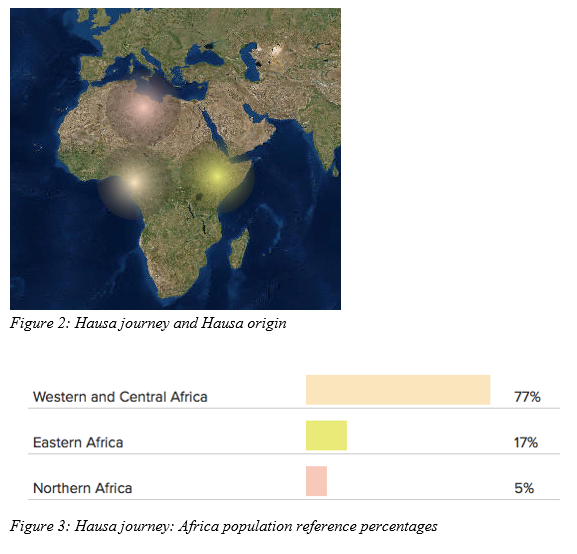

Result of the analysis of the data from the supplied as released by the Genographic Project can be summarized into three main components; the pre-history, modern/history period and contemporary period. What I will do here is to take us through the stories of Hausa people distant ancestors and show how the movements of their descendants gave rise to their lineage today as outlined in the mapping.

Each segment on the map above

represents the migratory path of successive modern human groups that eventually

coalesced to form Hausa people branch of the tree. The first start is the

marker for the oldest ancestor, and walk forward to more recent times, showing

at each step the line of Hausa people ancestors who lived up to that point, Malumfashi (2018).

According to the result, as each

individual carries his own DNA; which is a combination of genes passed from both our mother and

father, giving us traits that range from eye color and height to athleticism

and disease susceptibility, we the take the shape we pass on to others, Malumfashi

(2018). As part of this process, the

Y-chromosome is passed directly from father to son, unchanged, from generation

to generation down a purely male line.

Mitochondrial DNA, on the other

hand, is passed from mothers to their children, but only their daughters pass

it on to the next generation. It traces a purely maternal line, Malumfashi (2018).

Since the DNA is passed on

unchanged, unless a mutation - a random, naturally occurring, usually harmless

change - occurs. We are what we pass on to generations, yet unknown. The

mutation, known as a marker, acts as a beacon; it can be mapped through generations

because it will be passed down for thousands of years, Malumfashi

(2018).

When geneticists identify such a

marker, they try to figure out when it first occurred, and in which geographic

region of the world. Each marker is essentially the beginning of a new lineage

on the family tree of the human race. Tracking the lineages provides a picture

of how small tribes of modern humans in Africa tens of thousands of years ago

diversified and spread to populate the world.

By looking at the markers one

carry, geneticists can trace one lineage, ancestor by ancestor, to reveal the

path they traveled as they moved out of Africa. The investigation begins with

ones earliest ancestor. In this case the Hausa people ancestral lineage. Who

were they, where did they live, and what is their story? The story can be found

in the various branches of Hausa origin genetic tress traversed from about

150,000 years ago. This is Hausa people’s story as captured by the study of the

Hausa data supplied.

The common direct paternal ancestor

of all men alive today was born in Africa: 300,000 and 150,000 years ago, known

as “Y-chromosome Adam.” He is the only male whose Y-chromosome lineage

is still around today. All men, including my direct paternal ancestors, trace

their ancestry to one of this man’s descendants.

Around 100,000 years ago a mutation

occurred in the Y chromosome of a man in Africa. This is one of the oldest

known mutations that is not shared by all men. Therefore, it marks one of

the early splits in the human Y-chromosome tree. The man who first carried this

mutation lived in Africa and is the ancestor to more than 99.9% of paternal

lineages today.

Around 80,000 years ago, the BT

branch of the Y-chromosome tree was born. Some of this man’s descendants would

begin the journey out of Africa, into Middle East and India. Some small groups

from this line would eventually reach the Americas. Other groups would settle

in Europe. Some would remain near their ancestral homeland in Africa,

(Malumfashi, 2017). Individuals from this line whose ancestors stayed in Africa

often practice cultural traditions that resemble those of the distant past;

hunter-gatherer societies, the Mbuti, Biaka Pygmies of central Africa and

Tanzania’s Hadza.

The first group of male lineages,

the M168 branch was one of the first to leave the African homeland,

(Malumfashi, 2017).

The man who gave rise to the first

genetic marker in my own lineage lived in Northeast Africa.

Where? In the region of the Rift Valley, in present-day Ethiopia, Kenya,

or Tanzania. Scientists put the most likely date for when he lived at around

70,000 years ago. His descendants became the only lineage to survive outside of

Africa, making him the common ancestor of every non-African man living today.

My ancestor and his family were

nomadic as they moved around they followed the good weather and the animals

they hunted, the exact route they followed remains to be determined. This

mutation is one of the oldest to have occurred outside of Africa, (Malumfashi,

2017). Moving along the coastline, members of this lineage were some of the

earliest settlers in Asia The first migrants likely ventured across the Bab-al

Mandeb strait. A narrow body of water at the southern end of the Red Sea

Crossing into the Arabian Peninsula, developing mutation P143, perhaps 60,000

years ago (Malumfashi, 2017). By 50,000

years ago, they had reached Australia. These were the ancestors of some of

today’s Australian Aborigines.

Fluctuation in climate may have

contributed to my ancestors’ exodus out of Africa. The African ice age was

characterized by drought rather than by cold. Around 50,000 years ago, the ice

sheets of the Northern Hemisphere began to melt. A short period of warmer

temperatures and moister climate pervaded Africa and Middle East, parts of the

inhospitable Sahara briefly became habitable, (Malumfashi, 2018).

As the drought-ridden desert

changed to a savanna, the animals hunted by my ancestors expanded their range,

moving through the newly emerging green corridor of grasslands.

The first man from the data to

acquire mutation M578 was among those that stayed in Southwest Asia before

moving on. Fast-forwarding to about 40,000 years ago, the climate shifted

once again and became colder and more arid, (Malumfashi, 2017 and 2018).

Drought hit Africa and the Middle

East and the grasslands reverted to desert. The next 20,000 years, the Saharan

Gateway was effectively closed. With the desert impassable, my ancestors had

two options: Remain in the Middle East, or move on. Retreat back to the home

continent was not an option then.

The next male ancestor in my

ancestral lineage is the man who gave rise to P128, a marker found in more than

half of all non-Africans alive today. This man was born around 45,000 years ago

in south Central Asia, (Malumfashi, 2017 and 2018).

Some of the descendants of P128

migrated to the southeast and northeast, this lineage is the parent of several

major branches on the Y-chromosome tree:

O, the most common lineage in East

Asia.

R, the major European and Central

Asia.

Q, the major Y-chromosome lineage

in the Americas.

The final tree branch of the Hausa people from the genetic analyses

conducted is tagged V88, (Malumfashi, 2018), which was put at 5,600 – 9,200

years ago as the latest migratory pattern of the Hausa people. The result further

shows the Hausa people were born as the Earth entered the mid-Holocene epoch,

some early descendants of this lineage expanded into the Levant region and into

Europe. Others took part in a migration across Africa, (Malumfashi, 2017 and 2018).

These African travelers lived in a time when the Saharan region

changing from a lush land of savannas and woodlands to arid desert. As the

climate changed, the earliest ancestors of the Hausa people moved first to the

central Sahara and then on to the Lake Chad Basin. They brought with them the

proto-Chadic language. (Malumfashi, 2018), thus, they are the ancestors of all

Chadic language-speaking groups. Today, geneticists have found men from this

lineage at minimal traceable frequencies in Europe. From the deeper analysis of

the genetic sample it is found that the present day Hausa people’s lineage can

be classified into the following:

About 20 percent of Egyptian Berbers from Siwa.

It consists of about 6 percent of Southern Egyptian (ancient Egypt)

male lineages.

It is also present at low frequencies in Jewish Diaspora and Saudi

Arabian population groups.

It is about 20 percent of the Hausa male population as at now. (Malumfashi,

2017 and 2018).

In Central Africa, the lineage is present in high frequencies, most

especially amongst:

Ouldeme people of Northern Cameroun (96 percent)

Mada people of Western Cameroun, (82 percent)

Mafa people of Northern Cameroun and Eastern Nigeria, (88 percent). (Malumfashi, 2017 and 2018).

Further scrutiny shows this component of Hausa people’s ancestry is

associated with the region that extends from:

Senegal in West Africa.

South and East of Africa.

Nigeria to Congo and Angola.

It covers more than half of sub-Saharan Africa.

Prehistorically, this part of the world is one of the first reached

by modern humans some 100,000 years ago.

Historically, west and central Africa saw the rise and fall of many

empires and cultures. (Malumfashi, 2017

and 2018).

For a fuller understanding of where the journey took our

ancestors to and where they can be located, this map gives an indication.

Red Areas: Indicates high concentrations

Algeria and Democratic Republic of Congo

Light Yellow and Grey: Indicate low concentrations.

Saudi Arabia

Sudan

Egypt

Libya

Parts of Mali and Mauritania

Niger

Chad

Central Africa Republic

Parts of Nigeria

Parts of Cameroun

Parts of Ethiopia, (Malumfashi, 2017 and 2018).

This mapping shows the closest

haplogroup in the paths of Hausa people that geneticists have frequency

information for as Hausa close relations in indigenous populations from around

the world. This provides a more detailed look at where some of my more recent

ancestors settled in their migratory journey.

What do geneticists mean by

recent? A few hundred years to a few thousand years ago, depending on how much

scientists currently know about Hausa particular haplogroup. As scientists test

more individuals from Hausa region and receive more information worldwide, this

information will grow and change, (Malumfashi, 2017 and 2018).

One should sound a note of caution

here; the geographic region with the highest frequency show here isn’t

necessarily the place where the Hausa haplogroup originated, although this is

sometimes the case. In order for us to learn more ancestry information about

where Hausa haplogroups settled in more recent times, we need to do two things:

Contribute the results

(Malumfashi, 2017 ad 2018) to Science and fill out Hausa ancestry information.

Search for volunteers from amongst the Hausa people and other related people from around the movement regions of the world and have them tested genetically.

Conclusion

Taking all these into considerations and knowing that science is not

fully an exact study; a data from one individual cannot suffice for a thorough

and fuller research. There is the need to cover about 3,000 people, spread in

so many locations, within the West African substratum to the North and Central

Africa and even beyond to Asia for us to have a batter glimpse.

This is an interesting beginning of a journey, but then since the

task is to unravel more from the genographic point of view, so as to balance

the equation as regards the interconnectivity and interrelatedness of the

corpus as unearthed by historians, anthropologists, linguists, archeologists,

political scientists, sociologists and such others, this has opened up the

virgin area for more scrutiny. This is the main crux of this and other

researches in the future.

REFERENCES

Adamu, Mahdi. (1978) The Hausa Factor in

West African History, Ahmadu Bello University Press and

Oxford University Press, Nigeria

Alnaes, K. (1989). Living with the Past: The

Songs of the Herero in Botswana. Africa 59.3:

Barber, K. (1997). Preliminary Notes on

Audiences in Africa. Africa 67.3:

Barber, K. (1999). Quotation in the

Constitution of Yoruba Texts. Research in African Literatures 30.2:.

Bauman, R, and Charles. B. (1990). Poetics

and Performance as Critical Perspectives on Language and Social Life. Annual

Review of Anthropology 19:.

Belcher, S. (1999). Epic Traditions

of Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

DeAngelis S. (2019). https://www.enterrasolutions.com/blog/stem-vs-arts-

humanities/

Derive, J. (1995). The Function of Oral Art in the

Regulation of Social Power in Dyula Society. In Power, Marginality and

African Oral Literature. Ed. Graham Furniss and Liz Gunner. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press:.

Farias, P. de M. (1992). History and Consolation:

Royal Yoruba Bards Comment on Their Craft. History in Africa 19:.

Feierman, S. (1994). Africa in History. The End of

Universal Narratives. In Imperial Histories and Postcolonial Displacements. Ed.

Gyan Prakash . Princeton: Princeton University Press:.

Gunner, L. (2002a). The Man of Heaven and

the Beautiful Ones of God. Writings from a South African Church. Leiden:

Brill.

Hintjens, H. M. 2001.When Identity Becomes a Knife:

Reflecting on the Genocide in Rwanda. Ethnicities 1.1:.

James, D. (1997). Music of Origin’: Class, Social

Category and the Performers and Audience of Kiba, a South African Genre. Africa

67.3:.

Lange D. (2019) The Assyrian factor in West

African history, in: Wim van Binsbergen (ed.), Rethinking

Africa`s Transcontinental Continuities, Leiden 2012 Conference, Hoofddorp,

Lange D. (2018) The traditions of Gulfeil, in: P.

M. Mosima (ed.), A Transcontinental Career (2018),

Shikanda Press, Hoofddorp, Netherlands.

Lange D. (2013) New evidence on the foundation

of Kanem: Zaghawa Origins“, in: T.

El-Miskin et al., Kanem-Borno: A Thousand Year of Heritage, Ibadan

Lange D. (2012) The Bayajidda legend and

Hausa history, in: E. Bruder and T. Parfitt (eds.), Studies

in Black Judaism, Cambridge.

Lange D. (2004c) Ancient Kingdoms of West Africa:

Africa-Centred and Canaanite-Israelite Perspectives (A

Collection of Published and Unpublished Studies in English and French),

Dettelbach.

Last M. (2004) Before Kebbi: Written Evidence for a

Rima Valley State at Gungu Before 1500 AD, KADAURA Journal,

KASU, Kaduna

Malumfashi, I. (2017). The results of GENOGRAPHIC

PROJECT analysis—Malumfashi personal journey, Washington D.C

Malumfashi, I. (2018). The results of GENOGRAPHIC

PROJECT analysis—Malumfashi deep ancestry, Washington D.C

Mudimbe, V. Y. (1994). The Idea of Africa.

Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Muhammad, D. (1979). Interaction between the Oral

and the Literate Traditions of Hausa Poetry. Harsunan Nijeriya 9:.

Muhammad S. S. and Boyd.

J.(1974) Fassarar Infak̳ul Maisuri of Muhammadu Bello Sultan of

Sokoto North West State History Bureau

Nyembezi, C. L. S. (1948). The Historical

Background to the Izibongo of the Zulu Military Age. African Studies 7:

Palmer, H. R. (1929) Sudanese Memoirs.

Vol. III. Lagos, Govt. Printer

Shreeve J. (2006) http://eebweb.arizona.edu/courses/ecol223/Greatest_Journey_NG_06.

pdf

Smith, M. G. (1978). The Affairs of Daura:

History and Change in a Hausa State 1800–1958. Berkeley and Los Angeles:

University of California Press.

Smith, A. (1987) A little new light:

Selected historical writings of Professor Abdullahi, Adullahi Smith

Centre for Historical Research, Zaria Nigeria.

Suso, B, and Banna K. (1999). The Epic of

Sunjata. Trans. Gordon Innes with Bokari Sidibe, ed. and introd. Graham

Furniss and Lucy Duran. London: Penguin.

Usman, Y. B. (1981) The Transformation of

Katsina, 1400-1883 :

the Emergence and Overthrow of the

Sarauta System and the Establishment of the Emirate, Ahmadu Bello

University Press, Zaria /

Vansina, J. (1984). Art History in Africa. London:

Longman.

Vansina, J. (1985). Oral Tradition as

History. Oxford: James Currey.

Vansina, Jan . 2000. Useful Anachronisms: The

Rwandan Esoteric Code of Kingship. History in Africa:.

Wells S. (https://youtu.be/a-YKAaky7s),

Wells S. (2007) Deep ancestry: Inside the

Genographic Project: The landmark DNA Quest to Decipher Our Distant Past.

National Geographic Society.

0 Comments

ENGLISH: You are warmly invited to share your comments or ask questions regarding this post or related topics of interest. Your feedback serves as evidence of your appreciation for our hard work and ongoing efforts to sustain this extensive and informative blog. We value your input and engagement.

HAUSA: Kuna iya rubuto mana tsokaci ko tambayoyi a ƙasa. Tsokacinku game da abubuwan da muke ɗorawa shi zai tabbatar mana cewa mutane suna amfana da wannan ƙoƙari da muke yi na tattaro muku ɗimbin ilimummuka a wannan kafar intanet.