Paper presented at the 24th International Convention of the Association of Nigerian Authors, held on 11th-12th November, 2005 at the Murtala Muhammad Library Complex, Kano

Read to Reel:

Transformation of Hausa

Popular Literature from Orality to Visuality

Prof. Abdalla Uba Adamu

Department of Mass Communications

Bayero University, Kano – Nigeria

(Vice-Chancellor of the National Open University of

Nigeria)

auadamu@yahoo.com

Introduction

The transition from literature, or more specifically creative fiction to visual fiction

in the form of films, and

now video films, is a path rarely trodden in African literary societies. This comes about because of the strict division

between literary pursuits

and cinema. Literature is often seen as a more serious

domain of popular

culture, reflecting as it does, a poetic interpretation of life. Cinema,

on the other hand, is often considered a pure entertainment medium.

Yet filmmaking constitutes a form of discourse

and practice that is not just artistic and cultural, but also intellectual and political. As product of the imagination,

filmmaking constitutes at the same time a particular mode of intellectual and political practice. Thus, in looking

at filmmaking, in particular, and the other creative

arts, in general, one is looking at particular

insights into ways of thinking and acting on individual as well as

collective realities, experiences, challenges and desires over time.

The video medium provides

a very interesting opportunity for studying the transition of the transformation of the same

spectrum of creative arts. This is illustrated by the transition in Hausa folktale from orality to drama to literature

and eventually to the video film.

Although the Hausa video film industry covers all parts of northern Nigeria,

including non-Hausa speaking

areas, nevertheless its antecedent roots

were in Kano, the largest

commercial center in the north of Nigeria. The Hausa language also

provided the industry with a unique opportunity for development, principally because of its vastly cosmopolitan nature. Its use extends from

northern Nigeria all the way to Nigeria, Republic

of Benin, Cameroon, Togo, Ghana, and Sierra Leone – further spread by itinerant Hausa traders. The end product

was that the language became a lingua

franca in northern

Nigeria, absorbing other languages and becoming a medium of communication

even among those whose primary language is not Hausa. Indeed it even provides mutually non-legible

non-Hausa to communicate to each other, thus

often displacing English

as a medium of communication. Ironically, it is this success of the language

that is to be a bane of the problem

of the Hausa video industry. This is because a language is inevitably tied

down to cultural identity; when non-Hausa started entering

the Hausa video film industry, their representation of a cosmopolitan lifestyles clashed with the mainstream conservative Hausa

mindset and created a critical

tension between what the ethnic Hausa see as a pollution of their cultural values, and what video filmmakers see as a

modernization of the language and lifestyle of the people.

In this paper I would trace the development of Hausa visual literacy by first tracing Hausa popular culture from its antecedent oral roots, its transition to folkloric opera and indigenous drama before looking at the effect of media technologies that transform the oral-literary process to visual literature. I present this transition via the following diagram which shows how media technologies played a significant role in the reversal of visual literature to oral literate in contemporary Hausa popular culture.

Fig. 1. Media

technologies and transitions in Hausa popular

culture

The

figure traces flow of creative pursuits in Hausa indigenous literature and the various

inputs into the development of each genre by media technologies.

Oral Narratives and Mental Animated

Graphics

The

traditional tatsuniya folktale is the

quintessential antecedent to Hausa popular culture.1

As the fountainhead of Hausa oral literature it provides a filmic canvas on the life of a Bahaushe (ethnic Hausa) in a

traditional society. Aimed mainly at children,

the tatsuniya is an oral script aimed

at drawing attention to the salient aspects

of cultural life and how to live it in a moralist manner. It is necessarily a female

space, for as argued by Ousseina Alidou

(2002b, p.139),

In Hausa tradition, the oldest woman of the household or neighborhood— the grandmother— is the “master” storyteller. Her advanced age is a symbol of a deep experiential understanding of life as its unfolds in its many facets across time and she is culturally regarded as an important source of knowledge production, preservation, and transmission. This matriarch becomes the mediator/transmitter of knowledge and information across generations… She uses her skills of storytelling to artistically convey information to younger generations about

1 My focus on orality is restricted to popular culture,

rather than the whole gamut of oral literature which

might encompass historical accounts, heroic epics, riddles and jokes, proverbs,

e.t.c.

the culture and worldview,

norms and values, morals and expectations. Her relationship with her younger audience of girls and

boys…puts her in a position to educate, through her tatsuniya, about taboo

topics such as sexuality, and shame and honor, that culturally prevent parents

and children from addressing with one another.

Thus devoid

of male space,

the tatsuniya necessarily becomes

a script on how to live a good life devoid of threatening

corruptions. Strongly didactic and linear (without subtle sub-plot developments considering the relatively younger age of the audience), it connects a straight line between what is good and what is bad and the consequences of stepping out of the line. The central

meter for measuring the “correctness” and morality

of a tatsuniya is the extent to which

it rewards the good and punishes the bad. Its linearity

ensures the absence of conflict resolution scenes

which present moral

dilemmas for the unseen audiences. In cases where such moral conflicts

exist—for instance theft

situations—the narrator simply summarizes the scene. The reason for the linearity as well as the deletion, as

it were, of conflict resolution scenes is attributed to Islam. As Ousseina Alidou (2002a p. 244), building

up on the earlier works

of Skinner (1980)

and Starratt (1996)

points out,

The impact of Islam on oral

literary production in Hausa culture has been multifold. First, the inception of Islam in Hausa culture

infused the themes, style, and language of Hausa oral literature with an Islamic ethos and aesthetics. Its mode of

characterization also took a turn towards

a more Islamic conception of personal conduct that defines a person as

"good" or "evil"

Furthermore, many modern Hausa epics and folktales contain metaphorical

allusions to spaces relevant

to Islamic history and experiences.

The

imaginative structure of the tatsuniya does

not stop merely at narrative styles; it often builds

complex plot elements

using metaphoric characterizations. Animals thus feature prominently, with Gizo, the

spider taking the role of the principal character, although alternating between being good and being bad. One would

even imagine traditional tatsuniya tellers using computer animation

for their stories—for the animations used

in Hollywood cinematic offerings such as Madagascar,

Racing

Stripes, Shark Tale, Shrek, Antz, Finding Nemo—all aimed at metaphorically exploring the human psyche superimposed on the animal

kingdom—could be seen as perfect

renditions of the Hausa tatsuniya using

the power of modern media technologies.

A good example of this multiform structure is the story of The Gazelle has married a

human, in which a gazelle transforms into a beautiful maiden and entices a young man to marry her and live

with her parents. When she is sent to the vegetable garden

to fetch a vegetable for soup, she transforms into gazelle again,

calls all her fellow animals

and get seriously

down with song and dance routines—a bit like scenes

from the Hollywood film, The Lion King.

Other

plot elements explored within the tapestry of the tatsuniya include ethnic stereotyping

of “Maguzawa”2 and non-ethnic Hausa, as well as “absorbed” Hausa such as Kanuri,

Sakkwatawa, Tuareg, Nupe; and country

folks (bumpkins, simpletons, peasants). This is significant

because Alidou (2002b, p. 137), arguing from

the perspective of a Nigeriène Hausa, in her definition of what constitutes Hausa, argued that

2 It is interesting that acquisition of Islam has divided the Hausa community into two—“Maguzawa”,

i.e.

Hausa who did not accept any revealed

religion, and “Hausawa”, i.e. Hausa who predominantly accept

Islam (although there are many Hausa who are Christian, but not classified as Maguzawa).

The term Hausa is used to

refer broadly to a putatively multi-ethnic and predominantly Muslim community of speakers of Hausa as a native language. Over the centuries

the neighboring peoples from

various ethnic backgrounds (e.g., some Fulani, Kanuri, and Nupe) have adopted Hausa identity simply

by virtue of linguistic assimilation.3

Yet the persistence of Nigerian Hausa folktales often casting albeit

muted, asperation on other ethnic groups that have been

absorbed as Hausa “Banza Bakwai”4 clearly indicates a subtle internal sub-categorization of Hausa mindset

based on historical factors. Moralization, however, constitutes the largest percentage of the core messaging

of the tatsuniya, with most of the

moralizing focusing on issues such as ingratitude,

acts of God, poverty, etc. Within this framework are also interspersed comedies

revolving around tall stories or lies.

The

coming of Islam to Hausaland in about 1320 lent a more religious coloration to the folktales and further reinforced the moral aura of their themes. The reinforcement of separate spaces for the genders in

Islam consequently reflect the gender-space specificity of the Hausa tatsuniya. The gender space is described

and clearly delineated—and this further underscores the moral imperative of the tatsuniya narrator who often improvises on the stories.

Thus within this framework, the tatsuniya

scripts do not provide for the exploration of the female

intimisphäre, but for the reinforcement of gender stratification of a male dominated society.

This antecedent gender space

limitation of the Hausa folktale mindset would come under serious challenge from the visualization

of the Hausa folktales when transition is made to video

medium.

A study of the thematic classifications of the tatsuniya by

Ahmad (2002) reveals

plot elements that,

interestingly, resonates with commercial Hindi film plots and created creative convergence points for Hausa

video filmmakers to use the tatsuniya plot elements, if not the direct stories,

couched in a Hindi film masala frame. These themes according to Ahmad (2002) include unfair

treatment of members

of the family which sees

various family conflicts focusing on favoritism (as for example in the Kogin

Bagaja folktale), unfair or wicked treatment of children (Labarin Janna da Jannalo), and disobedience to parents (The girl who refuses

to marry any suitor with a

scar). This is supplemented by the second theme of the tales, which

included reprehensible behavior of

the ruling class or those in positions of authority. Sub- themes included forced marriage (Labarin Tasalla

da Zangina), arrogance

by members of the ruling elite

(The daughter of a snake and a prince),

oppression (A leper and a wicked Waziri

and a Malam). Other themes

deal with deceptiveness,

3 Alidou’s interpretation of what constitutes ethnic Hausa has a problem

in that the examples she gave of Fulani, Kanuri

and Nupe are people with distinct cultural, ethnic and even racial identities and have not accepted the tag of “Hausa” merely

because they speak a cosmopolitan language—much as Asians

residing in Britain

do not accept the tag of being,

say, Welsh, simply

because they live in Aberystwyth and speak Welsh.

4 The

ethnicity of Nigerian

Hausa—perhaps different from Nigeriène Hausa—is

divided into two broad clusters of historical origin. The

first, the Hausa Bakwai (or the “original Hausa” where Hausa is the sole mother tongue) is made up of Hausa

city-states of Biram (Garun Gabas), Daura, Gobir, Kano, Katsina, Rano and Zazzau (Zaria), which form the nucleus of

Kano, North Central and North western states

of Nigeria and the portion of Niger Republic. The second cluster, Banza Bakwai

(the “dud” seven) is made up of city-states

where originally Hausa was spoken but not as a mother tongue and which included Gwari, Ilorin (Yoruba),

Kebbi, Kwararafa (Jukun), Nupe, Yauri and Zamfara. The division between Hausa Bakwai and Banza Bakwai,

even though contemporarily trivial, confers on the “true

Hausa” (Hausa Bakwai

“citizens”) a feeling

of asali—true origins—to the Hausa mindset.

personal virtues and virtuous behavior. For further embellishment, some of tales in the tatsuniya

repertoire contain

elements of performance arts where the storylines merges

into a series of songs—often with a refrain—to further add drama

to the story.

Thus

the tatsuniya is an encyclopedia of

scripts read night after night to millions of

children all across Hausaland—no matter how geographically defined—as

night entertainment—at least before

the media intrusion of television first and digital satellite TV later.

The Tatsuniya as Opera

–

Street Tashe Drama

The

concept of drama is not a recent phenomenon in Hausa communities. Drama clubs and societies had had along history

in Kano going back to traditional court entertainments

during festivals. Indeed records from the histories of old Kano dating back to the founding of the city since

950 CE or so revealed a structured focus on drama, music and entertainment. Thus drama and theater had always been a structural component of Hausa traditional entertainment and styles.

Consequently,

with an effective performance arts matrix in place, the Hausa street drama therefore became the next evolutionary stage of tatsuniya

when children started picking

up elements of the moral storylines of the tales and began to mimic them, first

around the home, and then later around community centers. What emerged

was tashe—a series of street dramas normally

performed from the 10th day of the Ramadan. The often night festival lasts

for about 10 to 15 days and encompasses a series

of mimesis and enactment, as well as musical forms. Considering the gender bias of the tatsuniya towards reproducing the Hausa female worldview, it is not surprising that a significant portion of the tashe drama centers

on domestic responsibilities as main plot elements.

Umar (1981 p. 4) explains that tashe,

derived from tashi (wake up) refers to the fact that children could not wake up

in the middle of the night and engage

in household chores—which makes nighttime a source of daytime activities while food is being prepared for sahur (night breakfast). They therefore

amuse themselves with a series

of over 30 games and theater, most focused on simulating the household activities of adults—partaking, early enough, concepts

of domestic orientation and responsibility. Thus while tatsuniya is

an adult script,

tashe drama is an interpretation of the script using child (and

often, but not always, adult) actors.

Although performed

in various categories – ranging from comedy to serious drama

– the plays and theater

during tashe serve to focus the

creative energies of youth and provide them with a vital opportunity to contribute to the social

life of their individual societies. Virtually each of the tashe plays

has a theme that deals with social

responsibility or illumination. I will illustrate with a few of them.

Baran Baji is performed by a group

of six or so children

up to 14 years. The principal character in the drama often dresses

in female clothing

and carries the accouterments used by women in processing food which

include stone grinding mill (dutsen nika)

, circular mat for covering pots

and vessels (faifai), sieve (rariya) and others. During the performance the character goes into the process of actually processing the foodstuff of the

household the group enter, with the chorus group egging “her” on with a song and chorus. The focus of the

drama is to instill a sense of responsibility

and at the same time educate children

(especially girls) about household chores.

Ka Yi Rawa is also performed

by a group of six to eight children with one of them dressing up like a Malam—Islamic teacher—complete with a white

beard (made from cotton),

a carbi (Islamic rosary), a mat, an allo(wooden Qur’anic writing slate for pupils),

and an ink pot—the perfect

Muslim teacher. The song and chorus of this play was

admonishing the teacher on dancing, with him strenuously denying and indeed pointing

out the symbols of scholarship as possible deterrent

to him engaging in such folly.

When they refuse to believe him, he decided to actually perform a jig to prove he can dance. The main point of the play

is to draw the attention of the Muslim teacher

class of the fact that the eyes of the community are on them, and everyone looks up to them for proper decorum

and behavior.

Macukule, performed

by young men (as opposed

to children) is a parody with a focus on ethnic deconstruction of various

ethnic groups in Nigeria by mimicking their characteristics

in a song and chorus fashion, with the lead singer reeling out the various

behaviors of a specifically targeted

group. The ethnic

groups are not, perhaps tactfully, specifically identified and a

generic ethnic label of Gwari is

used. And although Gwari does refer to a specific ethnic group in Kaduna

basin; in this particular play

the term is used to refer to non-ethnic Hausa (bagware). In this way, the

Macukule performances serve to

illuminate their audience about specific group

traits and behaviors of other ethnic

groups.

Similarly,

Jatau Mai Magani, performed by young

men focuses attention on the medicinal properties of various shrubs,

trees, leaves and plants in the community, and in a powerful

song and chorus

fashion serves to illuminate the audience on indigenous medicine, with the song ending in a

declaration of the absolute of powers of the

Creator to heal – not the shaman (boka, marabout) or herbalist.

Neither

was the tashe theater restricted to

males only; girls equally participate in communicating

to the community their understanding of their eventual social roles and responsibilities in a series of

theater that included Samodara, Ragadada, Mai Ciki, and A Sha Ruwa. For instance, in Ga Mairama Ga Daudu, two girls dress as

a “husband” and “wife” with an song

and choir group trailing them. The group then

enacts not only how a wife should dress to please her husband, but also

how she can relate and communicate

with him to hold his attention. The entire script is sung by one of the choir girls,

with the “newly

weds” acting to the script.

Thus

in the elements of these street performances we often see reflections of gender stratification—perhaps not unexpected in a strictly

Islamic society, as indeed manifested itself in the original tatsuniya folktale. The assumption of

cross-gender roles in Ga Mairama Ga Daudu, for instance, is

necessitated by the social and religious

convention of gender segregation which makes it impractical to combine adolescent boys and girls in a simulated marriage

situation. Consequently, right

from the start, Hausa theater

had a focus on gender segregation and in a didactic style, emphasize female social responsibilities.

However, with the increasing Islamication of northern

Nigeria, the girls’

portions of the tashe theaters

gradually began to

disappear.

By 2005 very few female tashe troupes

were found in urban Kano; with their places

replaced by boys who used to dress in female

clothing.5

And while tashe is an organized activity

with specific spatial

configuration – performed in household or streets where

the artistes are given money for their performance – children also engage in a series

of games and plays that reflect theater

outside of the tashe festival

settings. A vivid example of this is Langa.

This is a strenuous physically

demanding game engaged by male adolescents only. It is a competitive sport with two teams of anything from six and above

players, each team with a camp. It

is played with the players standing on the right leg, with the left bent at the knee and held in place by the right arm. The idea is that the two teams represent two warring “nations”, and the players are the warriors, who

are “killed” by the simple act of being pushed down on the ground – an easy thing to do considering the players are

hopping on one leg. However, the strategy is to avoid being “killed” by running as fast as possible to one’s

“encampment”. The players whose “warriors” were

brought down most often are considered losers, and must therefore pledge allegiance to the winners. The game/drama

serves to emphasize territoriality and group cohesion.

With

more imaginative embellishment, the Hausa theater had, of course, since then undergone significant transformations,

starting first as a guild-related activity before crossing over to religious performances in the Hausa

bori cult systems. As pointed out by Kofoworola (1987, p. 11),

Assessed on the basis of

their magico-religious functions, the ritual forms of enactments in Hausa performing arts such as dance, mime,

imitative movements, mimicry and acting could

be regarded as a legacy

of the past traditions.

The

coming of Islam in about 1320 to Hausaland significantly reduced the religious tones of these performing arts, but nevertheless left a strong

template for an effective popular culture. Indeed associated with a

ruling class right from its inception, drama

had developed into various forms in Emirs’

courts throughout northern

Nigeria. Thus Wasan

Gauta, which metamorphosed into Wasan

Garma; Wasan ‘Yan Kama and Wawan Sarki

were all sophisticated theater initially aimed at the entertainment of the palace, but eventually re-enacted for the

ordinary citizens in the civil society. This

further led to the development of similar groups in the form of, for

instance, ‘Yan Gambara and ‘Yan

Galura performing artistes who combined comedy, theater and music in public

street performances.

Orality to Scripturality in Performing Arts

The logical development of the tatsuniya is the Wasan Kwaikwayo – written play. The written play, like the tatsuniya, is seen as a more serious

narrative, thus in the transition to

the written play, the tashe—considered

essentially as a child-related activity—is by-passed

completely by the newly Western-educated authors of the new literary genre. Wasan Kwaikwayo

emerges in Hausa popular

culture as a sophisticated

5 This was observed during the shooting

of a documentary I was filming on the Hausa traditional theater during the Ramadan period of 2005 (beginning from 15th

October 2005) which lasted for two weeks.

The boys dressed in girls’ clothes attracted the wrath of the dakarun Hisba (moral police in an Islamicate society) who attempted to

disband them, with the boys staying their ground and insisting on continuing with their performance.

virtual

literary tatsuniya, downloaded and

made elegant by the boko script which distinguishes the “educated” play from the

unlettered oral tatsuniya folktale in

the Western sense. In Hausa

oral literature, the tatsuniya

is the country

simpleton cousin of the Wasan Kwaikwayo.

Seeking a more intellectual sophistication, and fresh from reading set texts of Western literature, early educated Hausa public intellectuals adopted the boko script to create a more

metallic tatsuniya that departs from

the animals and monsters metaphors and addresses the central cerebral

sphere of a more sophisticated urban, educated audience. Sliding on the scale from

political metaphors to acerbic wit, it provides an intellectual legitimization of the Hausa oral verse.

The

written play took its more structured form with the publication of Six Hausa

Plays in 1930 by Rupert East, the British colonial

officer in charge of Hausa

Literature. Targeted at primary school pupils, it seeks to formalize the

community theater and further

emphasize the transition from orality of Hausa literature which

saw the transformation of tales to written

form. As Pilaszewicz (1985 p. 228) pointed out,

Hausa plays, as folk tales

did, concern themselves with family situations, with problems connected with marriage and polygamy to

the fore. They discuss the upbringing of young

people and protest against moral decline, but also deal with some more

general problems of social inequalities.

The introduction of Six

Hausa Plays in the formal educational curriculum in 1930 provided a template around which other

issues could be explored beside family dramas.

The first to seize this opportunity of using drama as a platform for social education was Mohammed Aminu Yusuf, better

known as Mallam Aminu Kano (1920-1983), a social critic,

philosopher, radical activist

and social reformer

(or, as he preferred, redeemer, after

establishing the People’s Redemption Party, PRP in the run- up to

the 1979 elections in Nigeria). He was, as the name suggests, based in Kano, although

with a wide circle of influence all over northern

Nigeria. His ideas eventually

crystallized in party political manifestos aimed at “people’s redemption” from what Aminu Kano interpreted as class oppression by traditional ruling hierarchies

in the emirates of northern Nigeria. He also became the first to formally write drama between

1938-1939 while a teacher in Middle School,

Kano. He subsequently taught at Kaduna College

where he founded the Dramatic Society. Through

drama and theatre Aminu learnt how to express issues in a humorous, sometimes

satirical and way. As a teacher in Kaduna College,

he wrote many plays in which

he criticized the

exploitation of the masses and challenged the system of emirates in northern Nigeria. In the play, Kai wane ne a kasuwar Kano da ba za a cuce ka ba? (Whoever you might be, you will be cheated at Kano

market) he depicted the exploitation of country people by heartless merchants, while in Karya Fure take ba ta ‘ya’ya (A lie blooms but yields no fruit) he raised the problem of excessive

taxes levied upon the Hausa rural population. In the years 1939-1941 Aminu Kano wrote

around twenty short plays for the use of schools

in which he ridiculed some of the outdated local

customs as well as the activities of

the Native Authority in the system

of indirect colonial

administration (Pilaszewicz (1985 p. 228).

Other plays included Alhaji Kar ka Bata Hajin Ka which admonished people not to be taken in by the superficial life of

modern western ways. Through his plays Aminu

ridiculed the old fashioned ways of life,

and even humorously satirized the British

and

their colonial

attitudes. With a combination of all these,

and learned in Qur’an, fluent

in Hausa and English languages, a good sense of humor and above all his

ability to sustain the listening attention

of his audience, Aminu Kano began a smooth transition to his future political life. Perhaps not surprisingly, none of these plays were published

when he submitted them to the Hausa language newspaper, Gaskiya Ta Fi Kwabo. The traditional establishment was too entrenched to accept literary

criticism, especially from one of them.

The years after Nigerian

independence in 1960 saw a greater interest

in the development of the drama script as a basis for social education.

Thus a whole clutch of plays were

published from 1967 to 1984 by what eventually became Gaskiya Corporation. These included Uwar Gulma (A.M. Sada), Tabarmar Kunya (Adamu Dangoggo and David Hofstad), Bora da Mowa (U.B. Ahmed), Malam Muhamman (B. Muhammad), Matar

Mutum Kabarinsa (Bashir F. Roukba), Shehu

Umar (U. Ladan and D. Lyndersy), Kulba Na Barna (U.D.

Katsina), and Zaman Duniya

Iyawa Ne (A.Y.

Ladan)

Scripturality to Visuality—TV Drama

One

of Malam Aminu Kano’s pupils in the Middle School Kano was Maitama Sule, who was to carry on the mantle of the

drama as an instrument of social messaging –

although without the acerbic social criticism. Maitama Sule, a social

philosopher, politician and

international diplomat (becoming Nigeria’s Ambassador to the United Nations) and an orator,

was subsequently made the Danmasanin Kano—a traditional title

borrowed form Katsina and conferring on the owner the status of a public intellectual. Maitama Sule’s interest in

drama was intensified when he watched a stage

drama of the Bayajidda legend performed by the pupils of Wudil Elementary School in 1937. He was influenced by Aminu

Kano’s use of drama as a form of education,

and from 1943 to 1946 while a student at the Kaduna College (long after Aminu Kano had left as a teacher), he became the president of the College’s

Dramatic Society which had been formed much earlier by Aminu Kano.6 After graduation from the

College, Maitama Sule was posted to his alma mater, the Kano Middle School in 1948 as a teacher. According to his biographer,

…his preoccupation with

drama took a wider dimension of thematic spread and audience. In school he established the dramatic

society, and was the master in charge of it. His dramatic activities went beyond the school. He established a city-wide troupe (Abubakar 2001 p. 41).

The

first play staged under Maitama Sule’s leadership of the Society of Middle School was Sarkin Barayi Nomau in 1948, with Maitama Sule playing the

principal character. The play was a

focus on brigandage. The special guest of honor in the audience was the then Emir of Kano, Alhaji Abdullahi Bayero who

was extremely impressed and amused by the performance. He subsequently became interested in the drama troupe and its activities and

indeed even instructed the Treasury to set aside some funds for the troupe

so that they might procure

costumes and other materials for their

plays. The troupe metamorphosed into Kano Drama Troupe and later, perhaps because of the official grants to them

from the Treasury, became part of the Kano Native Authority film Unit, all in 1948.

6 Interview with Alhaji Maitama Sule,

Danmasanin Kano, Thursday

21st July 2005,

Kano, Nigeria.

The

Kano Film Unit became the sole representative of Kano in any subsequent cultural festivals across the country, but

most especially at Kaduna where such festivals

were regular. When the Institute of Administration was opened in April 1954, it was the Kano Film Unit that

entertained the audience with a stage drama focusing

on how to run a local government council (and how not to run it). Perhaps due

to its non-aggressive themes, the Kano Film Unit was patronized by both the traditional establishment as well as the

colonial administration which used the Film Unit as a part of a civil society

orientation.

A transition was made in 1947 from stage theater

to radio drama when Maitama

Sule was appointed a member of the Advisory

Board for Radio Kano, with amongst others,

Alhaji Ahmadu Tireda.

The two of them decided

to stage plays

on the radio for wider

audience – which included the Emir Alhaji Abdullahi Bayero, and who

continued to be impressed

by their repertoire. It came to an end, however, when after a particularly impressive play Gudu Karin Haske, the Emir was so impressed he sent gifts to the cast. This offended Ahmadu Tireda’s sense

of dignity and pride who felt that as an artiste

he was performing an educative function, and not a beggar, and therefore rejected

his share of the gifts and stopped

participating in the radio drama

series. It did however continued

up to 1959 when Maitama

Sule became a Minister. Subsequently, some of the members of the Kano Film Unit decided to break away from this official dramatic society and formed a private

theatrical organization. They named it after

Maitama Sule by calling it Maitama Sule Film Unit.7 When it

was clear that funding for a

full-fledged film would not be forthcoming, the group simply called itself Maitama

Sule Drama Group.

When it was established in 1959, it contained what can, with a stretch

of the term, be said

to be the training ground

for “classical” Hausa

actors of the old brigade

(by 2005 most were either dead, debilitated by

old age, or gracefully ageing and appearing in

video films as grandfathers). These included Muhammadu Maude, Daudu

Ahmed Galadanci (aka Kuliya),

Mustapha Muhammad (aka Dan Hakki), Umar Uba Gaya (aka Doron Mage), Muhammad Gidado (aka Mr. G., and father of a

famous female video film artiste (2000-2005 period), Saratu Gidado who specializes in “cruel mother” roles).

Their early stage plays included

Kifi A Cikin Kabewa

and Ladi Kyaun Wuya, which were both comedies. Soon

they started attracting the attention of not

only members of the society, but also mentors and patrons in the form of

local wealthy men who sponsored their

plays. These patrons of the arts included Alhaji Nuhu Bamalli, Alhaji

Inuwa Akwa and Alhaji Gwadabe

Galadanci. The sponsorship enabled the group to stage plays about Islam and local

historical figures in Islam, most

especially the life of Shehu dan Fodiyo and his religious reforms in northern Nigeria.8

Soon enough the Maitama

Sule Drama Group attracted an invitation from the Sardaunan Sakkwato, then the Premier of

northern Nigeria, to participate in Festival

of Arts and Culture held for the first time in 1963 in Kaduna.

Their production, Bako Raba, Dan Gari Kaba, which was part of their repertoire, was based on the British

7 Interview with Alhaji Maitama Sule,

Danmasanin Kano, Thursday

21st July 2005,

Kano, Nigeria.

8 Information based on a Hausa-language

paper, Nasarori da Matsalolin Wasan

Kwaikwayo a Jihar Kano (Gains and Problems of Drama in Kano) by Alhaji Faruk

Usman, then Permanent Secretary/CEO CTV

67 Kano at the monthly lecture series of the Kano State History and Culture

Bureau on Thursday 29th January

2004.

colonial

conquest of northern Nigeria and the subsequent political struggles for independence. It won the first prize at the festival. More than that, it also attracted the northern

Nigerian regional television authorities who sent a representative (then Patrick Ityohegh) to convince the drama

group to re-stage their drama in a studio for

Radio Television Kaduna for broadcast all over northern Nigeria. They

agreed, and this marked the first

transition from stage drama to television drama. It was so successful that they innovatively decided

to launch a television drama series on Shari’a

system, leading to one of the most successful religious programs in northern Nigeria

in the form of Kuliya Manta Sabo. It was only transferred to Kano when CTV 67 television station

was created in 1986.9

The

success of the Maitama Sule Drama Group stimulated the creation of other “production” companies. These included

Ruwan Dare Drama Group (1969) which included

Bashir Nayaya as its founding members; Janzaki Motion Pictures (1973) containing perhaps the largest contingent

of known Hausa video film stars; Yakasai Welfare Association (1976), Tumbin Giwa (1979), Gyaranya

Drama Club (1981)

and Jigon Hausa Drama Club

(1984), among others.10 These clubs were not professional in the sense of academically-trained theater

arts practitioners; but amateur affairs by

enthusiasts who have full-time regular jobs, and take on stage acting as

basically a hobby. With time, they

were able to perfect their act and establish themselves as professional TV drama and stage theater

practitioners.

In

May 1977 the then military Government took over all the regional television stations

via the promulgation of Decree

24 and created Nigerian Television Authority (NTA) with

its base in Lagos. The Decree which took effect retrospectively from April 1976 brought all the ten existing

television stations under the control of the

Federal Government of Nigeria. Being a Federal television house, the

main focus of NTA were on programs

aimed at fostering national unity, especially during the most turbulent years of Nigeria’s history

punctuated by military coups and countercoups.

The most notable

of these national

programs included Things Fall Apart, Checkmate, The

Village Headmaster, Behind The Clouds,

The New Masquerade, Mirror In The Sun, Cock Crow At Dawn, Jaguar, Aluwe, Basi & Co, Abiku, The Third

Eye, The Evil Encounter, Fortunes, Fiery Force, Igodo, Wings Against My Soul, Adio

Family and Ripples, among others.

Some of the stars of these drama

series moved on to establish

the Nigerian

video film industry, Nollywood. They included Zeb Ejiro (Ripples), Zack Amata (Cock Crow At Dawn), Bob Ejike (Basi & Co), Justus Esiri (the Headmaster of Village Headmaster), Nobert

Young (Family Circle), Liz Benson (Fortunes) and Lola Fani Kayode (Mirror in the Sun), among others.

These

drama series, national as they were, nevertheless reflected the fundamental social space of southern Nigerians—a world

culturally remote from Hausa northern Nigeria.

Further, although they shared antecedent origins in folktales with Hausa drama, nevertheless they were rooted in the cultural and linguistic norms and references of southern Nigeria.

For as Adedeji (1986 p. 35) pointed

out,

9 Interview with Alhaji Daudu Galadanci, the character actor

“Kuliya” of Kuliya Manta Sabo, Fim, July 1999 pp 42-43.

10 Sango, Muhammad Balarabe II (2004), The Role of Non-Governmental Organisations in the Development of Hausa Film Industry in

Kano, in Adamu, A.U. et al (eds)(2004) Hausa

Home Videos: Technology, Economy

and Society. Kano, Center for Hausa Cultural

Studies.

The theatre in Nigeria has

its origin in the cultural settings of the past and the vicissitudes of the present. The remarkable folklore of

the past with its rites and pastimes created a climate and a veritable

foundation for a variety of theatrical activities. The theatre tradition

is therefore a part of the

social and ritual life of the people embracing the totality of their way of life, habits, attitudes and

propensities. Although looked at as a form of entertainment in the first instance, yet a theatrical show is

regarded as an informal way by which the quality of life of the people can be

inculcated and enriched.

The

NTA drama series therefore appealed more to educated elites or cosmopolitan urbanites

(especially reflected in dramas such as Bassey & Co. with

its pidgin English

dialogue) with all their messaging about national unity and cultural

peculiarities of other ethnic groups

in Nigeria, than mainstream Hausa audiences. What exacerbated the situation of course was the lack of

specific Hausa drama that would have a wider

national appeal. It was only in 1984 that a Kano-based English language

drama, The Magaji Family was broadcast on the national television.

The programming schedule of the NTA

Kano in its early years reflected its nationalist outlook this, as shown in Table 2.1.

In Kano, CTV was established as a television station in 1981 to provide

“community television” to

viewers in Kano and environs. It early focus was on drama series and according

to Louise M Bourgault (1996,

p. 5),

Storylines were created out of the stream of urban gossip pervading the city of Kano. Producers transposed these stories to

suit their creative means and didactic purposes and to satisfy the demands of the television medium. Storylines were

submitted by other employees at the station, and sometimes by outsiders who were welcomed

by the station when submitting ideas for productions. Because of this free interchange of

ideas, and because the shows were completed

so close to air time, CTV was easily able to interact with its audience. Some producers were even known to frequent

public viewing centers to “eavesdrop” on their

audiences and to incorporate feedback

into developing storylines or future episodes.

It is interesting that the Wasan Kwaikwayo

repertoire of ready

scripts and plays

were not considered as bases

for the CTV dramas—or any, for that matter. In this regard, these products of Western-educated

playwrights were shunned by the new media technology

of television, and instead, a recourse to community stories—in effect reflecting antecedent preference for

tatsuniya and indigenous storytelling—was a preferred mode for creating

scintillating drama series

on CTV. Indeed one of the most

successful CTV dramas,

Bakan Gizo, about a forced married,

borrowed its antecedent storyline from tatsuniya folktales.

CTV and other Hausa-based television stations

around northern Nigeria

therefore provided a viewing alternative to the NTA dramas—an alternative that is rooted in the cultural traditions of Muslim Hausa,

with its strict

gender space delineation, respect for authority, and an encouragement of the acquisition of morally upright

behavior. It is this viewing

template that is to provide

a stumbling block to contemporary middle-aged Hausa male viewers to accept contemporary (2002-2005) Hausa video films.

Thus the coming of television changed the entertainment pattern of predominantly urban Hausa audiences. The old grandma

with the tall tatsuniya tales

seems to have gone with the wind. The New Age

generation of audience

has arrived.

Passage to India – Hindi Film Motifs

in Hausa Literature

Increasing

exposure to media in various forms, from novels and tales written in Arabic, to subsequently radio and

television programs with heavy dosage of foreign contents due to paucity of locally produced

programs in the late 1950s and early

1960s provided

more sources of Imamanci (Abubakar Imam’s methodology of literary

adaptation) for Hausa authors. The 1960s saw more media influx into the Hausa society and media in all forms – from the written

word to visual formats – was used for political, social and educational purposes.

One

of the earliest novels to incorporate these multimedia elements – combining prose fiction with visual media – and

departing from the closeted simplicity of the

earlier Hausa novels, was Tauraruwa

Mai Wutsiya by Umar Dembo (1969). This novel

reflects the first noticeable influence of Hindi cinema on Hausa writers who had, hitherto

tended to rely on Arabic and other European literary sources for inspiration. Indeed,

Tauraruwa Mai Wutsiya is

a collage of various influences on the writer,

most of which derived directly

from the newsreels

and television programming.11

It

was written at the time of media coverage of American Apollo lunar landings as constant

news items, and Star Trek television series as constant

entertainment fodder on RTV Kaduna. The novel chronicles the

adventures of an extremely energetic and adventurous teen,

Kilba, with a fixation on stars and star travel,

wishing perhaps to go “boldly

where no man has gone before” (the tagline from Star Trek TV

series). He is befriended

by a space traveling alien, Kolin Koliyo, who promises to take him to the stars, only if the boy passes a series

of tests. One of them involves magically teleporting

the boy to a meadow outside the village. In the next instance, a massive wave of water approaches the boy, bearing

an exquisitely beautiful smiling maiden, Bintun

Sarauta, who takes his hand and sinks with him to an undersea city, Birnin Malala,

to a lavish palace with Jacuzzi-style marbled

bathrooms with equally

beautiful serving maidens.

After refreshing, he dresses in black jacket

and white shirt

(almost a dinner

suit) and taken to a large hall to

meet a large gathering of musicians (playing

siriki or flutes) and dancers.

When

the music begins—an integrative music that included drums, flutes, and other wind-instruments, as well as hand-claps; all entertainment features

uncharacteristic of Hausa musical styles of the period—a

singing duo, Muhammadul Waka (actually Kolin

Koliyo, the space alien, in disguise) and Bintun Wake serenade his arrival in high-octave (zakin murya) voices, echoing singing duets of Hindi film playback singers,

Lata Mangeskar and Muhammad Rafi—the

Bintun Wake and Muhammadul Waka of Tauraruwa Mai Wutsiya. As fully narrated

in the novel:

The audience burst out in applause, and the band played on,

with drums, flutes in full symphony,

with drums beaten in low beats. Then the hall went silent, everyone waiting to

see what happens next, waiting for

the next movement from the musicians and the two singers. Then the drummers resumed their beat, old

men started shaking their feet, priests started shaking their heads, young men were shaking

their bodies—all swayed by the music. Everyone was waiting for the song to

start. Suddenly the lead drummer skidded as if he was leaving the hall. He pulled up his drum and went into solo beat,

making people wondrous of what was

about to happen. Then an incredibly sweet voice of oratorical proportions burst

out singing a beautiful song that

cools the heart. Everyone looked towards the sound to it was see Bintun

Waka (sic) who started her singing. Then she was joined by Muhammadul Waka, with

11 A.G.D. Abdullahi, Tasirin Al’adu da

Dabi’u iri-iri a cikin Tauraruwa Mai

Wutsiya. Proceedings of the First International Conference on

Hausa Language and Literature, held at Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria, July 7-10, 978. Kano, CSNL.

Kano, Center for the Study of Nigerian

Languages.

his own style of singing, swaying his body at the same time, while Bintun Wake joined him, also swaying her derriere and breasts.

This

scene, unarguably the first translation of Hindi film motif into Hausa prose fiction,

and which was to give birth to Hindinization of Hausa home videos, displays

the author’s penchant for Hindi films and describes Hindu temple

rituals; in Hausa Muslim music

structures, limamai (priests) do not

attend dance-hall concerts and participate.

In Hindu culture, however, they do, since the dances are part of Hindu rituals

of worship. Plate

1 shows the poster a Hindi film inspiration, Bahut Din Huwe (1954) and the cover

of the Hausa novel (1969).

Other

Hindi films that lend their creative inspiration in the novel’s dancing scene included Hatimahai (1947) and Hawwa

Mahal (1962) with their elaborate fairytale- ish stories of mythology and adventure.12

Reel to Read—Novelists as Filmmakers

More

direct availability of media technologies in the 1970s created opportunities

for the leap from written

literature to film medium, via oral literature. The direct link between literature and film, however, was

made only in 1976 when the late director Adamu

Halilu filmed Shehu Umar—one of the

five stories that were selected by the British colonial

administration in a literary competition in 1933. Shehu Umar is a vast chronicle of the life and times

of the eponymous turn of the century

figure whose life story he traces in this narrative about Islam in West Africa.

The

success of Shehu Umar, the film,

provided inspiration for consideration of film

adaptations of other Hausa literary

classics. Thus 1987 saw the appearance of the film

version of Ruwan Bagaja—the first adapted novel by Abubakar

Imam, which was

12 I acknowledge, with gratitude the help offered

by Sani Lamma who identified the scene in Tauraruwa Mai Wutsiya and suggested that

it seemed to be a collage from these three Hindi film. Kano, April 10, 2004.

again

part of the famous “first five” novels written in 1933 under the auspices of

the Translation Bureau. The

didactic nature of these novels was emphasized by their being midwifed by the Directorate of Education, and were aimed

directly at primary school pupils.

In

the subsequent film adaptation of Ruwan

Bagaja, Kasimu Yero played the role of

Alhaji Imam while Haruna “Mutuwa

Dole” Danjuma played Malam Zurke bn Muhamman. These two novels—Ruwan Bagaja and Shehu Umar—however remained the only ones to be translated into the film medium

from the stable of the first five Hausa novels

published in 1935.

By 1980, the Northern

Nigerian Publishing Company,

NNPC, the main media publishing house in Northern Nigeria,

had virtually stopped publishing prose fiction

works, restricting itself to recycling of the old classics as well as

more educational materials. The

process of publishing became a cash-and-carry affair with authors being charged for printing of their works (e.g. Balaraba

Ramat Yakubu’s Wa Zai Auri Jahila?). Most of the prospective new authors did not have the fund to get their works

printed by the major publishing houses.

With media parenting in the form of increasing

deluge of television and radio programs

imported from Asia, it was only a matter of time before the template provided

by Tauraruwa Mai Wutsiya

started providing a basis for writing stories

with Hindi cinema themes of

love and romance from early 1980s. Thus a new crop of Hausa indigenous authors

then emerged from 1980 with the appearance of So Aljannar

Duniya by Hafsat AbdulWahid, the first Hausa-speaking Fulani female novelist. This heralded the arrival of a

new age generation. The modern classical Hausa writers

(e.g. Suleiman I. Katsina, Bature

Gagare) of the early 1980s

seemed to have retired their pens, since most of

them were one-hit wonders; producing a text that

was well received and used as a textbook for West African School Certificate Hausa examinations. Just like the Hausa

classical (e.g. Abubakar Imam, Abubakar Tafawa

Balewa) and neoclassical (Abdulkadir Dangambo, Ahmadu Ingawa) writers before them, they enjoyed the patronage

of the State or multinational corporate publishing

houses, eager to cash on the burgeoning high school population, freshly spewed from the pools of the mass educational policy of Universal

Primary Education (UPE)

scheme of 1976.

When

stringent economic reforms (‘austerity’) hit, the publishing companies felt it, and they had no option but re-prioritize

and withdraw their patronage of vernacular works.

It took two competitions (1978 and 1980) to tease out more writers who fall neatly into the third generation, but

still using the modern Hausa mode. Some, however,

hark back at the classical Hausa formats (e.g. Amadi Na Malam Amah which can draw a parallel with Ruwan Bagaja).

The newcomers

gate-crashed the Hausa literary scene with ballistic

urbanism, divesting readers

from the village simplicity of the earlier Hausa classics of heroes, demons, monsters and evil rulers. They

were cultural cyborgs: an uneasy confluence

between the two rivers of Hausa traditionalism and modern hybrid urban technological society. Strangely enough,

they did not build on the thematic styles of

their “modernist uncles” of the 1980s. Neither did they pay any homage

to the tatsuniya stable of scripts, considering tatsuniya a “fiction” with no basis in reality.

Further

the new generation of writers avoided giving too much attention to Marxist politics (as, for instance in the earlier Tura Ta Kai Bango), gun-toting

dare-devils, drug cartels (e.g. as in

Karshen Alewa Kasa), prostitution or

alcohol consumption. Writing in

uncompromising and unapologetic Modern Hausa (often interlaced with English words to reflect the new urban

lexicon of Ingausa), they focused

their attention on the most emotional concern of urban Hausa youth:

love and marriage; thus falling

neatly into the romanticist mold, or soyayya.

In

this respect, they unwittingly borrow antecedents from the European sentimental

novel. This is because, as was the case of the 18th century European

genre, the new Hausa prose fiction soyayya writer exploits the reader's

capacity for tenderness, compassion,

or sympathy to a disproportionate degree by presenting a beclouded or unrealistic view of the subject. In

Europe, the genre arose partly in reaction to the austerity and rationalism of the Neoclassical period. The

sentimental novel exalted feeling

above reason and raised the analysis of emotion to a fine art. This was perfectly reflected in the saccharine dialogs, often interlaced with bursts of long songs characteristic of the new Hausa romantic

fiction.

The

economic boom of the country had gone into nosedive by the time these literary “mercenaries” and stalwarts arrived.

Thus they were not guaranteed schools to proceed after high schools; and no

automatic scholarships wait for them. For many

who were able to eke out living,

in petty artisan

occupations (e.g. cap-making, sewing clothes) or

lowly clerical chores in government offices, their next attention was settling

down and getting

into a humdrum of a family life.

For many it was a shock to learn

that they cannot marry their loved ones due to their abject poverty, and that

the girl of their dreams

(literally) had been given away, often against her wish, to a rich pot-bellied Alhaji with tons of cash to sway everyone’s minds. For many, these experiences were enough to convert them to

neophyte literati, and the focus of their angst

is clearly outpouring of imaginary romanticism. Thus the soyayya genre made its appearance. Consequently one of the most successful books of the emergent genre was

the autobiographical In Da so Da Kauna by

Ado Ahmad Gidan Dabino, written in anger in 1990 and published

in 1991. Other writers, especially the women, see life through

the prism of a soap opera and therefore chronicle

the day-to-day experiences of kishi (resentment amongst co-wives) and the issue of female empowerment through

making it clear that girls have a choice in deciding the direction of

their lives. No matter the medium of

expression, the end message is clear: personal empowerment, and the right to choice.

It is this message that drew the flak on the themes

and subject matter

of their writing.

Thus emerged

the genre of Hausa Popular

Literature, contemptuously labeled

Labaran Soyayya and Kano

Market Literature, 13 which by 2002 had produced more than

700 titles (Furniss

2004) – thanks to the increasing availability of cheap printing

presses. Pioneers in the genre included Ibrahim

Saleh Gumel’s Wasiyar Baba Kere

13 Malumfashi, Ibrahim., “Adabin

Kasuwar Kano”, Nasiha 3 & 29 July

1994. The first (?) vernacular article in which Ibrahim

Malumfashi created the term Adabin Kasuwar

Kano (Kano Market

Literature), a contemptuous

comparison between the booming vernacular prose fiction industry, based around Kano State (with Center of Commerce

as its State

apothegm) and the defunct Onitsha

Market Literature which flourished around Onitsha market

in Anambra State in the 1960s. In 2005 Graham Furniss, on the basis of various interactions with

Abdalla Uba Adamu and Yusuf Adamu created the term Hausa Popular Literature (HPL) to describe

the genre.

(1983);

Inda Rai Da Rabo (1984) by Idris S.

Imam, and Rabin Raina I (1984) by Talatu

Wada Ahmad.

When

in the early to mid 1990s the VHS camera became affordable, a whole new visual literature was created by this

first crop of contemporary Hausa novelists. As

Graham Furniss noted,

One of the most

remarkable cultural transitions in recent years has been this move from books into video film. Many of the stories

in the books now known as Kano Market Literature or Hausa Popular Literature are

built around dialogue and action, a characteristic that was also present in earlier prose writing of the 1940s and

1950s. Such a writing style made it

relatively easy to work from a story to a TV drama, and a number of the Hausa

TV drama series (Magana Jari Ce, for example) derived their story lines from texts.

With the experience of staging

comedies and social commentaries that had been accumulating in the TV stations and in the drama department of ABU, for example, it was not difficult conceptually to move into video film.14

Yusuf

Adamu was able to link a number of the new wave of Hausa novels with their transition to the visual

medium, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Hausa novels adapted into Home Videos

|

S/N |

Author |

Novel

to Video |

|

1. |

Abba Bature |

Auren Jari |

|

2. |

Abdul Aziz

M/Gini |

Idaniyar Ruwa |

|

3. |

Abubakar Ishaq |

Da Kyar Na Sha |

|

4. |

Adamu Mohammed |

Kwabon Masoyi |

|

5. |

Ado Ahmad

G/Dabino |

In Da So Da Kauna |

|

6. |

Aminu Aliyu

Argungu |

Haukar Mutum |

|

7. |

Auwalu Yusufu

Hamza |

Gidan Haya |

|

8. |

Bala Anas

Babinlata |

Tsuntsu Mai Wayo |

|

9. |

Balaraba Ramat |

Alhaki Kwikwiyo |

|

10. |

Balaraba Ramat

Yakubu |

Ina Son Sa Haka |

|

11. |

Bashir Sanda

Gusau |

Auren Zamani |

|

12. |

Bashir Sanda

Gusau |

Babu Maraya |

|

13. |

Bilkisu Funtua |

Ki Yarda Da Ni |

|

14. |

Bilkisu Funtua |

Sa’adatu Sa’ar Mata |

|

15. |

Dan Azumi

Baba |

Na San A Rina |

|

16. |

Dan Azumi

Baba |

Idan Bera da Sata |

|

17. |

Dan Azumi

Baba |

(Bakandamiyar) Rikicin Duniya |

|

18. |

Dan Azumi

Baba |

Kyan Alkawari |

|

19. |

Halima B.H.

Aliyu |

Muguwar Kishiya |

|

20. |

Ibrahim M. K/Nassarawa |

Soyayya Cikon

Rayuwa |

|

21. |

Ibrahim Mu’azzam Indabawa |

Boyayyiyar Gaskiya (Ja’iba) |

|

22. |

Ibrahim Birniwa |

Maimunatu |

|

23. |

Kabiru Ibrahim Yakasai |

Suda |

|

24. |

Kabiru Ibrahim Yakasai |

Turmi Sha Daka |

|

25. |

Kabiru Kasim |

Tudun Mahassada |

|

26. |

Kamil Tahir |

Rabia15 |

14 Graham Furniss, Hausa popular literature and video film: the rapid rise of cultural

production in times of economic

decline. Institut für Ethnologie und Afrikastudien, Department of

Anthropology and African Studies,

Arbeitspapiere / Working Papers Nr. 27. Institut für Ethnologie und

Afrikastudien, Johannes Gutenberg-Universität, Forum

6, D-55099 Mainz,

Germany.

15 This

was different from Rabiat by Aishatu

Gidado Idris who abandoned the project of converting her novel into a home video.

|

S/N |

Author |

Novel

to Video |

|

27. |

M.B. Zakari |

Komai Nisan Dare |

|

28. |

Maje El-Hajeej |

Sirrinsu |

|

29. |

Maje El-Hajeej |

Al’ajab (Ruhi) |

|

30. |

Muhammad Usman |

Zama Lafiya |

|

31. |

Nazir Adamu

Salihu |

Naira da Kwabo |

|

32. |

Nura Azara |

Karshen Kiyayya |

|

33. |

Zilkifilu Mohammed |

Su Ma ‘Ya’ya

Ne |

|

34. |

Zuwaira Isa |

Kaddara Ta Riga

Fata |

|

35. |

Zuwaira Isa |

Kara Da Kiyashi |

After

Adamu (2003)16, with additions

Literary adaptations to cinematic medium,

of course, is as old as the media themselves. In world literature such

adaptations included Cry, The Beloved

Country (Alan Paton),

Schindler’s List (Thomas Keneally), The Silence of the Lambs (Thomas Harris), A Room with a

View (E.M. Forster), Jurassic Park (Michael

Crichton), The Handmaid’s Tale (Margaret Atwood), Sense and Sensibility (Jane Austen), Jane Eyre

(Charlotte Bronte), The Hunt for Red October (Tom

Clancy), The Prince of Tides (Pat

Conroy), Contagion (Robin

Cook), The Last of the Mohicans (James

Fenimore Cooper). Each of these produced

a block-busting film that, in varying degree provided a creative footnote

to the original written script.

When

the new wave of Hausa writers started producing, in massive quantities, prose fiction interlaced with love stories and

emotional themes, literary and textual critics

started comparing their storylines with Hindi films,

with accusations that they rip-off

such films.17 Thus the Hindi film Romance was

claimed to be ripped-off as Alkawarin

Allah by Aminu Adamu.18 Similarly, it was argued by

Ibrahim Malumfashi that the transition

to Visuality was first through prose fiction of the more prominent writers with passing nods to Hindi cinema. Citing an example,

he claimed that

Bala Anas Babinlata’s (novel) Sara Da Sassaka is an adaptation of the Indian film Iqlik De Khaliya

(sic) while his Rashin Sani is

another transmutation of another Indian film, Dostana, etc.19

And yet he contradicted his textuality when in 2002 he wrote:

Complaints against the Kano

Market Literature in its halcyon days focused on how mindsets alien to Hausa culture were reflected in

the novels, most especially direct borrowing of ideas that included Indian, European and Arabic media sources. For instance, Sara da Sassaka by

16 Yusuf Adamu, “Between the Word and

the Screen: A Historical Perspective on Hausa Literary Movement & the Home Video Invasion.” Adapted

from a paper presented at the 20th Annual Convention of

the Association of Nigerian Authors, Jos, 15-19th, November, 2000.

The paper was also published as Yusuf M. Adamu “Between the word and the screen:

a historical perspective on the Hausa

Literary Movement and the home video invasion”. Journal of African Cultural Studies, Volume 15, Number 2, December

2002, pp. 203-213.

17 Halima Abbas, “New Trends in Hausa

Fiction”, New Nigerian Literary

Supplement — The Write Stuff, 11, 18, July; 1 August,

1998. This was a post-graduate seminar presentation of the Department of Nigerian and African Languages, Ahmadu Bello University Zaria held on June 3, 1998 towards

an

M.A. degree.

18 Muhammad Kabir Assada,

“Ramin Karya Kurarre

Ne”, Nasiha, 16-22 September 1994, p. 4.

19 Ibrahim Malumfashi, “Dancing Naked in the Market Place”,

New Nigerian Weekly Literary

Supplement — The Write Stuff, July 10, 1999 p. 14-15. I confronted

Bala Anas Babinlata with this observation after it was published, and like all Hausa authors,

he strenuously objected

to the insinuation that they adapted Hindu cinema for their novels.

Interview, Kano, August,

1999.

Bala Anas Babinlata is an

adapted Indian film, Dostana; In So Ya Yi So by Badamasi Burji, was from Iglik De Khaliya (sic), while Farar

Tumfafiya by Zuwaira Machika was Kabhie Kabhie.20

It is

not clear here which of Bala Anas Babinlata’s novels is adapted from an Hindi film: Sara da Sassaka

(which Malumfashi claimed

in 1999 to be Dostana) or Rashin Sani

(claimed in 2002 to be Dostana).

Indeed, in a surprising turn of polemics, Ibrahim

Malumfashi, a writer and literary critic, was accused of adapting an Hindi film in his first novel, Wankan Wuta by A.S. Malumfashi, another writer, who argued:

“…Since the demise of the

legendary Alhaji Imam, many writers….have been trying to step into the shoes he bequeathed, but none of

them has succeeded. Such contemporary writers are legion; the indefatigable Ibrahim Sheme, the writer of The Malam’s Potion, Kifin Rijiya….Dr. Ibrahim Malumfashi, who intended to continue with Imam’s

famous Magana Jari Ce but ended up wasting his time writing the

serialized Wankan Wuta: a book that

questions the creativity of the

writer as it appears to be a hopeless plagiarism of an Indian film, Khudgarz, and Jeffrey Archer’s Kane

and Abel. Though they have through their various works been preserving Hausa literature as well as

promoting the reading habit among the Hausa people more than during the Imam era, unfortunately none of them has

matched Imam’s great genius and wisdom…”

(A. S. Malumfashi, New Nigerian Weekly, May 22, 1999,

p. 15).21

Brian

Larkin also provides arguments that seem to link the plot structures of Hausa novels of the 1990s with Hindi commercial

cinema themes, although he does not provide

a specific textual analysis that links a specific novel with a specific Hindi film.22 Larkin’s analysis, however was within the framework of what he calls “parallel modernities” that see a reproduction of convergent cultural

spaces between Hausa novelists and Hindi commercial cinema.

Women

novelists, particularly those with an ideological slant in their novels were quick to take on the opportunity provided

by the new visual medium

to illustrate their

messages. These included

Bilkisu Funtuwa, Zuwaira

Isa, Aishatu Gidado Idris (Rabiat,

abandoned production of a video with the same name due to “creative differences” with cast and crew) and

Balaraba Ramat Yakubu, whose first video (interestingly

not adapted from any of her novels) …Sai

A Lahira set some sort of record

in 2000 as the most expensive female-produced video in the industry at production cost of over one million

naira then about $7,407).

Balaraba

Ramat Yakubu, the most ideological of the female authors was the only female producer who set out to actively

portray a feminist/womanist ideology in her

videos. Most famously

known as the author of best selling

novels like Wa Zai Auri

20 Ibrahim A.M. Malumfashi, Adabi Da Bidiyon Kasuwar Kano A Bisa

Fai-fai: Takaitaccen Tsokaci. Paper presented at a Seminar

on New Methods of Hausa

Literature, and organized by the Center

for the Study

of Hausa Languages, Usmanu Danfodiyo University, Sokoto, 8-9th July, 2002.

21 See also Muhammad Qaseem, “Wankan Wuta ko Wankar Littafi?” Nasiha, Friday 11-17 November, 1994.

22 Larkin, Brian., “Modern Lovers:

Indian Films, Hausa Dramas and Love Novels Among Hausa Youth”, New Nigerian

Literary Supplement — The Write Stuff, February 21, 26 , 1997. This paper

was initially presented at the

African Studies Association Annual Meeting at Orlando, Florida, U.S., November 3-6 1995; Also published as

“Indian Films and Nigerian Lovers: Media and the Creation of Parallel Modernities.” Africa,

Vol 67, No 3, 1997,

pp. 406-439

Jahila?, Budurwar Zuciya, Ina Sonsa Haka, and Alhaki Kwikwiyo23 two of her novels, Ina Sonsa Haka, Alhaki Kwikwiyo

were converted into the video media. She wrote the original

novel, Alhaki Kwikwiyo which was

adapted for a screenplay and made into home

video. However, Ms. Balaraba Ramat Yakubu, the subject of international critical

study on her novels24 disowns

this particular video as her own in an interview with Fim magazine of

December 1999 (p. 30). She stated that only about 40% of the story narrated in the novel, Alhaki Kwikwiyo, was incorporated into

the video. Also she was not the one who developed the script for the video.25

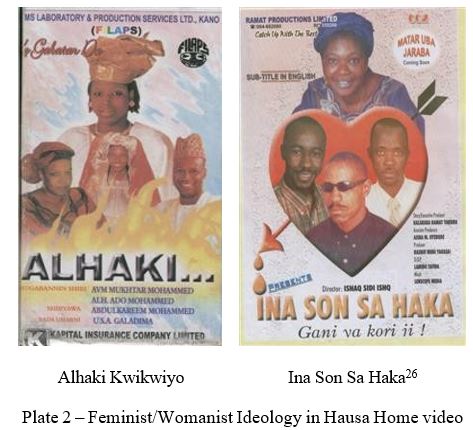

Alhaki.. and Ina Sonsa Haka, reflect her womanist interpretation of the determination of a Hausa woman to be independent within the boundaries of a traditional society. The posters for the two videos are shown in Plate 2.

Both the two videos

deal with a womanist anthem

that see a radical interpretation of a woman in a traditional society

(as opposed to feminism which seek political,

social

23 For a full discussion of

feminist/womanist discourse in Balaraba Ramat’s fiction, see Abdalla Uba Adamu (2003), Parallel Worlds: Reflective

Womanism in Balaraba Ramat Yakubu’s Ina Son Sa Haka. Jenda: A Journal of Culture and African Women Studies: Issue

4.

24 Two significant works included:

Novian Whitsitt, “The Literature of Balaraba Ramat Yakubu and the Emerging Genre of Littatafai na

Soyayya: A Prognostic of Change for Women in Hausa Society.” An Unpublished thesis submitted in partial

fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts (African Languages and Literature) at

the University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1996; and “Excerpts from Balaraba Ramat Yakubu, Alhalo Kwikwiyo (sic)” Translated

from Hausa by William Burgess, in Stephanie Newell(ed), Readings in the African

Popular Fiction. Indiana

University Press, 2002.

25 The script was sold to FILAPS, Kano,

who produced the video at the cost of N20,000 equivalent to about $154 in 1999. In a discussion with

one of the producers, AbdulKareem Mohammed, he retorted that they were not obliged to follow the book since they wanted

to make the video more visually appealing. Incidentally, Ms. Ramat was present when he made this remark.

26 For a critical and literary analysis

of Ina Son Sa Haka, the book from

which the video was derived, and which

explored Hausa Womanism,

see Adamu, A.U. (2003), “Parallel

Worlds”….

and economic

equity in a male-dominated society)

— initially abused and discarded, but bouncing back in full force and retaining the same traditional world view; but in a more detached

and independent manner.

Alhaki caused some furor due to its too many “adult” scenes (i.e. a hand casually

draped over inter-gender actors!), making some

critics to label it “batsa” (sexually dirty). As one viewer angrily

wrote in the letters page of Fim,

I want to talk about the

video, Alhaki Kwikwiyo…It is clear

this fim sets out deliberately to corrupt the upbringing of our children

because of nudity

and (soft) pornography in it…no right

thinking person, especially if they know what it contains, would buy the fim for his family

due to the bad scenes in

it..Alhaki Kwikwiyo bai dace ba (Alhaki Kwikwiyo is not proper), Alhaji Rabi’u

Uba, Unguwar Zango,

Kano, Fim, Letters page, March 2000 p.9.

For a traditional society,

the sight of a bare-chested man lifting his bride – a strategically clothed otherwise

bare-chested woman, looking suggestively into her eyes, and putting her down a bed and laying down beside her does

evoke feelings of outrage.27 This revealed a chasm between

filmmakers as literary

adapters and writers;

for while the writer was cautious in communicating “adult”

messages to predominantly young readers, the director

was more focused on creating a more visually appealing messaging.28

Ina Son Sa Haka,

based on the best-selling Hausa novel of the same name, chronicles the true-life story of a woman who was forced by her father

into marrying a husband she detests,

how she ran away from the situation, met another person who was stuck by tragedy and stood by him despite

strong opposition from her family.

Interestingly, it was based on a true story.

Conclusions

In the path trodden

by Hausa novelists in adapting their works to the video

film media (the only one affordably available to

them) they often chose to be the script writers, producers, directors, and often editors. This is not just to

avoid “creative difference” (as happened between

Hafizu Bello’s adaptation of Maje El-Hajeej’s novel Al’ajab as Ruhi29) but to ensure a control

in the production process, which included the marketing.

Interestingly enough,

the novelist filmmakers combined a series of motifs to transform

their written works into a visual fest. As noted earlier, forced marriage, co- wife

rivalry (kishi), oppression by

domestic authority (whether a constituted or

familial) are some of the key elements in Hausa folktale. These same

elements are reproduced in parallel

way in Hindi commercial cinema to which these authors were avid

fans. It is not surprising therefore that in putting down their creative

experiences, they created

a confluence of what they see as convergent cultures

in both their written prose

and visual depictions.

27 To show the extent of the

“conservatism” of Hausa video viewers, a similar outrage greeted a scene in Sa’adatu

2 in which a leading character appeared in a swimming trunk and entered a

privately secluded swimming pool. The

viewers’ reaction was that he appeared “naked” and that art should not be placed above religion and culture (see the angry

letters, and the actor’s response

in Fim, July 1999).

28 Discussions with the producer of Alhaki Kwikwiyo, Alhaji AbdulKareem

Mohammed, Kano, 18th January 2003.

29 Ruhi went

to become the first Hausa

video film to be awarded

the best actor in Hausa

films by a British-based entertainment company, Afrohollywood, in October 2005.

Shunning

the tatsuniya and its tashe variant as well as refusal to even

adapt some of the plays

to the visual medium conferred

on the filmmakers a new independence and control over the medium which are familiar with—having learnt the tricks

of the trade in the hard knocks

of life.

Yet textual

analysis of the early novel to film adaptations reveal

plot structures based

on traditional elements of story telling in modernized Hausa societies.

This indeed even led to adaptations of two tatsuniya into

the film medium.

These were Daskin Da Ridi

and Kogin Bagaja (which was based

on the plot elements of Ruwan Bagaja). These, however, did not catch on, and from 2000 an entire Hausa video film industry emerged

which based its scripts on ripping-off Hindi commercial cinema and converting them into Hausa. To date more

than 130 of Hindi films have been converted into Hausa language,

complete with song and dance routines.

Thus when the home video replaced

the novel as a more powerful—and subsequently more influential—mode of social interpretation, the morality of the messages

became a central