Guest Paper Presented to the University of Warsaw, 10th May, 2012, Department of African Languages and Cultures, University of Warsaw, Poland.

Al-Hausawi, Al-Hindawi: Media Contraflow, Urban Communication and Translinguistic Onomatopoeia Among

Hausa of Northern

Nigeria

Prof. Abdalla Uba Adamu

Department of Mass Communications

Bayero University, Kano – Nigeria

(Vice-Chancellor of the National Open University of Nigeria)

auadamu@yahoo.com

Introduction

In general, the purpose of translation—searching for cultural and semantic equivalents—is to reproduce various

kinds of texts—including religious, literary, scientific, and philosophical texts—in another language and thus making

them available to wider readers. However, the

term translation is confined to the written, and the term interpretation to the spoken (Newmark 1991: 35). Within this in

mind, comparing text in different languages inevitably involves a theory of

equivalence.

Equivalence can be said to be the central

issue in translation although its definition, relevance, and applicability within the field of translation theory have caused heated controversy, especially as the target text can never be equivalent to the source

text at all level. Thus many different theories of the

concept of equivalence have emerged, the most notable of which were by Jakobson (1959), Catford (1965), Nida and

Taber (1969), House (1977), Baker (1992)

and Vinay and Darbelnet (1995).

Catford (1965: 1994), for instance,

argues for extralinguistic domain of objects, emotions, memories, objects, etc. features which achieve expression in a

given language. He suggests that

translational equivalence occurs, when source texts (STs) and target texts

(TTs) are relatable to at least some

of the same features of this extralinguistic reality. However, according to Jakobson (1959), interlingual

translation involves substituting messages in one language for entire messages in some other language. Thus “the

translator recodes and transmits a

message received from another source. Thus translation involves two equivalent messages in two different codes” (Jakobson 1959: 114).

For Nida (1964)

there are two different types of equivalence, formal equivalence—which in the

second edition by Nida and Taber (1982) is referred to as formal correspondence—and dynamic equivalence. Formal correspondence 'focuses attention

on the message itself, in both form and content',

unlike dynamic equivalence which is based upon 'the principle of equivalent effect'

(1964:159). Formal correspondence consists of a target language

(TL) item which represents the closest equivalent

of a source language (SL) word or phrase. Dynamic equivalence is defined as a translation principle according to

which a translator seeks to translate the meaning of the original

in such a way that the TL wording will trigger the same impact on the target correspondence (TC)

audience as the original wording did upon the

source text (ST audience). Nida and Taber (1982: 200) further pointed

that ‘frequently, the form of the

original text is changed; but as long as the change follows the rules of back transformation in the source language, of

contextual consistency in the transfer, and of

transformation in the receptor language, the message is preserved and

the translation is faithful.’

Baker

(1992) provides a more detailed

list of conditions upon which the concept

of equivalence can be defined.

These conditions include: equivalence occurring at word level and above word level, when translating from one language

into another; grammatical equivalence, when referring to the diversity of grammatical

categories across languages; textual equivalence, when referring to the equivalence between a source language text and a target language

text in terms of information and cohesion; and pragmatic equivalence, when referring to implication and strategies of avoidance during

the translation process.

Finally, Vinay and Darbelnet (1995)

view equivalence-oriented translation as a procedure which replicates the same situation as in the original, whilst

using completely different wording.

This, in a way, is a transmutation of the original into target audience

cultural realities. Thus equivalence is therefore the ideal method when the translator has to deal with proverbs, idioms, clichés, nominal or

adjectival phrases and the onomatopoeia of animal sounds. Vinay and Darbelnet’s categorization of translation procedures is very detailed. They name two ‘methods’ covering

seven procedures: direct

translation (which covers

borrowing, calque and

literal translation) and oblique translation (which is transposition,

modulation, equivalence and adaptation).

There are three main reasons why an exact equivalence or effect is difficult to achieve. First,

as Hervey, Higgins

and Haywood (1995)

noted, textual interpretation is dynamic, and thus it is

difficult for even the same person to have the same interpretation of the same

text. Secondly, translation is often

a subjective process—if the objectivity of the text is non- contentious, then the subjectivity of the translator is not. Third,

time gap between

the original source

text and the equivalent translation leaves the translators uncertain about the impact of the original

source text on its audience

at the time of primary

contact.

Religious Text, Hausa Shamanism and British Translation Bureaus

The meaning of a given word or set of words is best understood as the contribution that word or phrase can make to the meaning or

function of the whole sentence or linguistic utterance where that word or phrase occurs. The meaning of a given word is

governed not only by the external object

or idea that particular word is supposed

to refer to, but also by the use of that particular word or phrase in a particular way, in a particular context,

and to a particular effect

– even if not conveying the same

meaning as the source text. This is where onomatopoeia comes in as a handy conceptual framework. According to Hugh Bredin (555-556),

The

strict or narrow kind of onomatopoeia is alleged to occur whenever the sound of

a word resembles (or "imitates") a sound that the word refers to. The words "strict" and "narrow" suggest

that the sense in question is a kind of original usage or

practice, in respect of which other senses of onomatopoeia are metaphorical or perhaps

extensional enlargements.

In his analysis

of onomatopoeia, Hugh Bredin (1996) created three categories of the translation device: direct onomatopoeia (the denotation of a word as a class of sounds,

and the sound of the word resembling a member of the class),

associative onomatopoeia (conventional

association between something and a sound and conventional relationship of naming between a word and the thing named

by it), and exemplary onomatopoeia (amount and character of the physical

work used by a speaker

in uttering a word).

In my use of the word

"onomatopoeia", I would want to the word to refer to a relation between

the sound of a word and something

else, and not connoting the meaning of the base word, or associative

onomatopoeia. This same understanding is used by Hausa shamans

who started using selected verses

of the Qur’an as vocal amulets in ritual healing

in Hausa

communities of northern Nigeria.

In his work on Hausa shamanism, Bello Sa’id refers

to the use of onomatopoeia in religious contexts among the Hausa as

“kwatanci-faɗi” (similar utterance). I refer to these religious-sounding utterances as vocal amulets. The following are few examples

(after Sa’id, 1997).

Example #1

Vocal amulet for winning a legal case – Qur’an (Shura) 42:13.

Original Qur’anic

transliteration: SharaAAa lakum mina alddeeni

mawassa

Onomatopeic Hausa version: Shara‘a lakum minaddiini maa wassee…”.

Original’s translation: “The same religion

has He established for you as that which He enjoined on Noah.”

In this vocal amulet, the shaman

focuses on two words – Shara’a, and wassee. The first, shara’a,

is familiar to Muslim Hausa as referring to Shari’a, the Islamic law; while the second word, wassee, sounds similar to the Hausa words, wasa (playfulness) and wasar (ignore, make redundant). Thus

this vocal amulet is meant to scatter any dispute involving the law in which the defendant is not sure of winning

the case. The shamans advocate

using only part of the original verses to fit in

with their perceived properties as amulets. It is clear that the verse refers

to a more historical incident;

and yet the shamans use the vocal similarities of the shortened verse as an amulet.

Example #2

Vocal amulet for locating a lost goat – Qur’an

80 (Abasa). 1, 2

Original Qur’anic

transliteration: AAabasa watawalla, An jaahu al-aAAma

Onomatopeic Hausa version: Abasa wa tawallee,

An jaa’ ahu la ‘amee.

Original’s translation: “ (The Prophet) frowned and turned away, Because

there came to him the blind man (interrupting).”

The key word in this vocal amulet is amee – which

vocalized in a high-pitched voice

sounded like a goat

bleating. The amulet is therefore used to locate a lost goat by being recited

over and over again. The word amee is

expected to be the main expression that will bring the goat back to its owner

by using the sound resonance of the bleat

embedded in the word.

Example #3

Vocal amulet for winning a wrestling match – Qur’an

105 (Fil): 1:

![]() Original Qur’anic

transliteration: Alam tara kayfa faAAala rabbuka bi-as-habialfeeli

Original Qur’anic

transliteration: Alam tara kayfa faAAala rabbuka bi-as-habialfeeli

Onomatopeic Hausa version: Alam tara kai…kayar shi

Original’s translation: “Seest thou not how thy Lord dealt with the Companions of the Elephant?”

In this amulet the beginning of the

expression is taken up to a point where a word appears with a Hausa equivalent, kai (you);

the word is shortened only to the point where it bears similarity with the Hausa word, then the shaman adds completely

new words to create a meaning,

kayar shi (throw him down; defeat him) – even though the new words were not part

of the original Qur’anic text (one of the many reasons the shamans are

shunned by Hausa Islamic orthodoxy). The amulet is used to empower wrestlers

– any wrestler reciting this over and over during an encounter is likely to

win the match by putting a hex on the opponent. A draw will probably

result if both opponents recite the same vocal amulet!

It is significant to note that the

Hausanized versions of the Arabic words—or associative onomatopoeia (Bredin 560)—used by the shamans

are not translations of the original

Qur’anic words, but serve “as the nexus of acoustic properties which

constitutes them as objects of consciousness for a normal

speaker of the language.” (Bredin

557). This is more so

as such onomatopoeia is governed by convention, not just the natural resemblance of the two words. This is illustrated, for instance, by a vocal amulet that serves as a warning

to Qur’anic school

pupils not to cheat:

Example #4

Vocal amulet to warn against grade skipping in Qur’anic education

– Qur’an 78 (An-Nabaa): 30 Original Qur’anic transliteration: Fa dhuuquu falan naziyadakum illaa ‘Adhaabaa Onomatopeic Hausa version: Fa zuƙu

falam nazida kumu illa azaba

Original’s translation: "So taste ye (the fruits

of your deeds); for no increase shall We grant you, except

in Punishment”

The keys to this amulet are zuƙu (skip, cheat), and illa (except) and azaba (harsh punishment). The Hausa onomatopeic use of

this verse is to discourage Qur’anic school pupils

from skipping a portion of their Qur’anic studies (a cheating process referred

to as zuƙu), and if they do cheat that way, they will face punishment (azaba). In this amulet two words are actually

translated, into the Hausa words – illa (except, but) and azaba (punishment) which share the same meaning

in both Arabic and Hausa. The Hausa shamans thus shift the focus of translation from

source text (ST) to target sound (TS)—for the

shamanic rituals are not written

but vocalized.

Consequently, common sense dictates

that any medicinal value attached to the original expression (if indeed

it had any in the context it was quoted

by the shaman) would be lost in the re-working of the expression into Hausa shamanistic language since the same meaning

is not conveyed in the

translation. Thus the Hausa shamans – considered little more than charlatans working on spiritual

gullibility of ignorant

Muslims, and thus occupying a narrow space in Hausa public

discourse – resort to vocal interpretations of selected expressions in the Qur’an to create a new meaning not

intended by the original source. As Walter Benjamin (1969: 71) argues,

Translatability is an essential quality of certain

works, which is not to say that it is essential that they be translated;

it means rather that a specific significance inherent in the original manifests

itself in its translatability.

The

translatability of the shamans’ interpretation of the selected

words and expressions in the Qur’an

for medicinal purposes

in this case appeals to less discerning members of the Muslim Hausa

public sphere who accept the shaman’s medicine

as curative – essentially because

it is derived from the Qur’an.

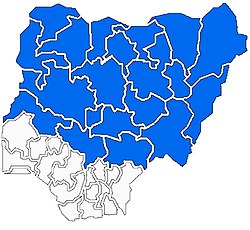

The Colonial Translation Bureau in Northern Nigeria

A second stage that was set for whole scale translations of popular

culture in northern

Nigeria was the antecedent set up by the British

colonial administration. When the British

colonized what later became

northern Nigeria in 1903, they inherited a vast population of literate citizenry, with thousands of Qur’anic

schools and equally thousands of Muslim intellectual scholars. A modern Western-oriented schooling system was created

in 1909. However, it lacks indigenous

reading materials. To address this problem the British set up a Translation Bureau initially in Kano in 1929, but

later moved to Zaria in 1931. The objectives of the Bureau were, amongst others, to translate books and materials from

Arabic to English, and later to

Hausa. Arabic was chosen because of the antecedent scriptural familiarity of

the Hausa with Islamic texts. This

saw Hausanized (roman script) versions of local histories in Arabic texts, notably

Tarikh Arbab Hadha al-balad

al-Musamma Kano, or Kano Chronicles as

translated by H. R. Palmer (1908). The Hausa translation was Hausawa Da Makwabtansu.

This was followed by a translation of

Arabic Alf Laylah Wa Laylah, a

collection of Oriental stories of

uncertain date and authorship whose tales of Aladdin, Ali Baba, and Sinbad the Sailor have almost become part of Western

folklore, and translated into Hausa by Mamman

Kano and Frank Edgar.

Similar strategies were adopted

by the British in India.

Modi (2002), argues

that as part of the British

East India Company's attempts to propagate western thought and education in the country, three universities were

established on western models—in Bombay, Calcutta and Madras. Through these universities, British drama began to be

introduced with an emphasis on the study of Shakespeare whose plays—in English

—began to be seen in various parts

of India and attracted new

audiences. This phenomenon also began to attract the attention of some Parsi businessmen who believed that

local adaptations of Shakespeare and even of

popular stories could be a source of potential profit. The result was

the establishment of several theatre

companies—known by all simply as Parsi Theatres because of the Parsi ownership—on a commercial basis. Their model was the many Victorian

commercial theatres in

operation in England. The first two of these new Indian groups were the

Victoria Theatre and the Alfred Theatre,

both established in 1871 and both of which ultimately toured widely. Other groups grew from these two

including the New Alfred Theatre and the Original Theatre. As audiences increased, Victorian-style theatre

buildings soon went up in many of India's larger cities, most of them copies of the Covent

Garden and Drury Lane in London.

Thus in India, as in Nigeria, there was

a studied attempt to encourage the popular culture of the Other especially through translations, which provided a

template for creative writers. In Nigeria,

the most exhaustive of the translators in Hausa prose fiction was Abubakar

Imam, who translated over 80 books,

poems and short stories from Middle Eastern, Asian and European tales into Hausa language in 1936. The result was Magana Jari Ce (talk is a virtue),

which became an unalloyed classic of Hausa literature. Malumfashi (2009)

provides a close look at how each

story was painstakingly transmutated into Hausa to convey not only the realities

of Hausa society,

but also its cultural parameters in stories that were never probably intended for other cultures.

The

original sources of the narratives in both Ruwan Bagaja (a frame novel stitched

from 19 different story sources by Abubakar Imam

in 1933) and Magana Jari Ce were

identified as Alif Laila, or Book of the Thousand

Nights and One Night (the

1839 edition translated by Sir William

Hay MacNaghten, although

other editions were also consulted

by Imam), Panchatantra (a book of Indian fables and folktales), which came to

Imam through the Arabic Kalilah wa Dimnah as translated by

Thomas Ballantine Irving (1980), Bahrul

Adab, Hans Andersen Fairy Tales, Aesop

Fables, The Brothers Grimm Fairy

Tales, Tales from Shakespeare, and Raudhul Jinan.

The northern Nigerian translation

activities therefore provided a further legitimate bases for translations – whether direct,

or in equivalence mode – of works of popular

culture. Subsequent

translations included Iliya Ɗan Mai Karfi

(translated from Ilya Muromets, a Russian folk poem), Sihirtaccen Gari (from a collection, Ikra, by Sayid Kutub), Abdulbaƙi Tanimuddari (A story of a hero –called

Abdulbaqi Tanimuddari) – translated from Arabic, Saiful Mulk, Hajj Baba of Isfahan

and the odd English book or so, such as Littafi Na Bakwai

Na Leo Africanus (The Seventh

Book of Leo Africanus), Robin Hood, Twelfth Night, Animal Farm and Baron Munchausen. Thus translation, whether

onomapoeic, equivalent, or regular, is a fully established mechanism

in Hausa popular

religious, literary, and as we shall now see, popular

culture.

Cinematic Antecedents in Northern Nigeria

Having

established a translating antecedents in Hausa

religious and popular

literature, I now turn

my focus to global media flows. In his essay on the current epoch of

globalization, Modernity at Large, Arjun Appadurai (1996) argues that globalization is characterized by the twin forces of mass migration and

electronic mediation, which provides alternative ways of looking at popular

consumption patterns. Appadurai

posits five dimensions of global cultural

flows, referring to them as ethnoscapes, mediascapes, technoscapes,

financescapes, and ideoscapes to connote that these dimensions take the form of roughly

fashioned landscapes. It is

in and through the disjunctures of each of these dimensions that global flows

occur. Mediascape, for instance,

points to the circulation and distribution of music media (tapes, CDs, MP3 files), networks of transmission

(satellite TV channels for music videos), and the flow of content itself. Consequently, the effect of such transnational

sharing is a greater diversity of music cultures, especially in traditional societies.

Appadurai therefore considers the way

images—of lifestyles, popular culture, and self- representation—circulate internationally through

the media and are often borrowed in surprising

and inventive fashions. This is reflected in the popularity of Hindi songs from films shown in cinemas and television stations

in northern Nigeria.

Cinema houses in northern Nigeria were

established by resident Lebanese merchants who, during the British colonial rule of Nigeria (from 1903 to 1960),

screened predominantly American and

British films, essentially for colonial officers. Despite being screened in a language few of the local audiences

undertood, neverthemeless cinema going became established as a social

activity, an experience that was always much more than the viewing of the film itself. This is reflected, for instance, in a letter

to the Secretary, Northern Provinces, Kaduna, by the then

Colonial Resident of Kano, E.K.

Featherstone who noted, while commenting on Film Censorship in Kano:

“Frequently

when I see films in Kano which I know are going to be shown on subsequent

nights to African audiences I realise how little suited

they are to an African

public. Among a large youthful

class of Kano City, Fagge and Sabon Gari which has money to spare in its pockets it has become the thing to do to go to the Cinema quite regardless

of whether they understand what they see and hear or not. For example, the other night I saw a large

African audience sitting attentively through an exhibition of “Night Boat to Dublin”. The next day an

educated Hausa admitted to me that he had been unable to understand what he had heard and seen in this film but that he

went regularly to the cinema to be seen and

to see his friends.” E.K. Featherstone, Resident, Kano Province, 13th January

1948 (Kano No G.85/94).

Thus whether they understand the plot

of the films or not, the mere process of going to cinema provided urban Hausa youth with a focal point of social

convergence that was to make the

spectacle of the cinema a central catalyst in the transformation of the popular culture

of the Muslim Hausa.

All cinemas in Kano before Nigeria’s independence in 1960 screened

American and Europeans films exclusively. No films from

either the Middle East or Asia were screened—

principally because the initial concept of the cinemas was targeted at

Europeans and settlers from other

parts of West Africa, who were not interested in non-European films. Thus the standard

fare was either

war, Roman history,

cowboys or historical films.

When Nigeria became independent from

British colonial rule in 1960, the Lebanese cinema owners took the unilateral decision to reduce the number of

European films and show films from

Asia, particularly India. It was not clear what motivated this decision; however,

it was likely that this was forced

on them by reduced European clientale and more interest from newly independent local residents – thus forcing

a rethink on the film screening policy.

There was an Indian community of sorts

in Kano. However, this remained aloof from the

local community, very much unlike the Lebanese who became heavily

involved in local commerce and indusry and learnt the Hausa language.

The Indian community

was predominantly made up of professionals – teachers, engineers, doctors – imported

during the economic prosperity of Nigeria

in the 1970s. They were not cultural

merchants, and had little interest

in the spread of their

culture – via an independent route – to the local community. A few,

however, did eventually got involved in retail trading of media products,

principally Hindi films on video tapes which

they imported from Dubai.

The Lebanese who owned the cinemas in

Kano at the time, and who decided what was screened,

were Christians, and the few Muslims amongst them were Shi’ite Muslims in contrast

to the dominant Sunni Islam of northern

Nigeria. The Lebanese

thus had little

reason to promote

Islamic films from the north

Africa (especially Egypt).

Since the main purpose of setting

up the cinemas for the local popular was entertainment, Hindi films with their spectacular sets, storylines that echo

Hausa traditional societies (e.g. forced marriage, love triangles of two men after the same girl, or two co-wives

married to the same man), mode of dressing

of the actors and actresses (hijab and body covering for women, long dresses

and caps for men), as well as the lavish

song and dances

would seem to fill the niche. Rex cinema (established in 1937) led to the way to

screening Hindi cinema in 1961 with Cenghiz

Khan (dir. Kenda Kapoor, 1957).

Thousands of others

that follow in all the other cinemas

included Raaste Ka Patthar (dir. Mukul Dutt,

1972), Waqt (dir. Yash Chopra, 1965),

Rani Rupmati (dir. S.N. Tripathi, 1957), Dost (dir. Dulal Guha, 1974) Nagin

(dir. Rajkumar Kohli, 1976), Hercules (dir. Shriram, 1964), Jaal (dir. Guru Dutt, 1952), Sangeeta (dir. Ramanlal Desai, 1950), Charas (dir. Ramanand

Sagar, 1976), Kranti (dir. Manoj Kumar, 1981),

Al-Hilal (dir. Ram Kumar.

1935), Dharmatama (dir. Feroz Khan,

1975), Loafer (dir. David Dhawan, 1996),

Amar Deep (dir. T. Prakash Rao, 1958), Dharam Karam

(dir. Randhir Kapoor,

1975) amongst others. From

the 1960s all the way to the 1990s Hindi cinema enjoyed significant exposure

and patronage among

Hausa youth.

And although predominantly based on

Hindu culture, mythology and traditions, there were very few Hindi films with an Islamic content

which glosses over the Hindu matrix, and which the Muslim Hausa readily identify with.

These faintly Muslim films (most adapted from

Arabian stories) included

Faulad (dir. Mohd. Hussien

Jr.,1963), Alif Laila (dir. K. Amarnath 1953),

Saat Sawal (dir. Babubhai

Mistry, 1971), Abe Hayat

(dir. Ramanlal Desai, 1955), and Zabak (dir. Homi Wadia, 1961) among

others. Interestingly, despite the strong influence of Pakistani Muslim scholars on Hausa Muslim youth in the 1970s

(especially through the writings of

Maryam Jameela, Syed Abu A. Maudodi), films from Lollywood (Lahore, Pakistan) were not in much favor, at least

in Kano. Thus by 1960s Hindi popular culture, at least what was depicted in Hindi films, was the predominant

foreign entertainment culture among

young urbanized Hausa viewers, and when the Hindi film moved to the small

screen TV, housewives at last became recognized in the entertainment ethos.

The increasing exposure to

entertainment media in various forms, from novels and tales written

in Arabic, to subsequently radio and television programs with heavy

dosage of

foreign contents due to paucity of

locally produced programs in the late 1950s and early 1960s provided more sources of Imamanci (Abubakar Imam’s methodology of adaptation) for Hausa authors.

The 1960s saw more media influx into the Hausa

society and media in all forms—from the written word to visual formats—was used for political, social and educational purposes.

One of the earliest novels to incorporate these multimedia elements—combining prose fiction with visual media—and departing from the

closeted simplicity of the earlier Hausa novels, was Tauraruwa Mai Wutsiya [The

Comet] by Umar Dembo (1969). This novel reflects the first noticeable influence of Hindi cinema on Hausa writers who

had, hitherto tended to rely on

Arabic and other European literary sources for inspiration. Indeed, Tauraruwa Mai Wutsiya is a collage of various influences on the writer,

most of which derived directly

from the newsreels and

television programming (Abdullahi, 1978). It was written at the time of media coverage of American Apollo lunar

landings as constant news items, and Star

Trek television series (first

created by Gene Roddenberry in 1966) as constant entertainment fodder on RTV Kaduna. The novel chronicles

the adventures of an extremely energetic and

adventurous teen, Kilɓa, with a fixation on stars and star travel,

wishing perhaps to go “boldly where

no man has gone before” (the tagline from Star

Trek TV series). He is befriended

by a space traveling alien, Kolin Koliyo, who promises to take him to the

stars, only if the boy passes a series of tests. One of them involves magically teleporting the boy to a meadow outside the village. In the

next instance, a massive wave of water approaches the boy, bearing an exquisitely beautiful smiling maiden, Bintun

Sarauta, who takes his hand and dives with him to an undersea city,

Birnin Malala, to a lavish palace with jacuzzi-style marbled bathrooms with equally beautiful serving maidens. After

refreshing, he dresses in black

jacket and white shirt (almost a dinner suit) and taken to a large hall to meet

a large gathering of musicians (playing

siriki or flutes) and dancers.

When the music begins—an integrative

music that included drums, flutes, and other wind- instruments, as well as hand-claps; all entertainment features

uncharacteristic of Hausa musical styles

of the period—a singing duo, Muhammadul Waƙa (actually Kolin Koliyo, the space

alien, in disguise) and Bintun Waƙe serenade his arrival in high-octave (zaƙin murya) voices, echoing singing

duets of Hindi film playback

singers, Lata Mangeshkar and Muhammad Rafi—the

Bintun Waƙe and Muhammadul Waƙa of Tauraruwa Mai Wutsiya.

This scene, unarguably the first

translation of Hindi film motif into Hausa prose fiction, and which

was to give birth to Hindinization of Hausa video films, displays

the author’s penchant

for Hindi films and describes Hindu temple rituals; in Hausa Muslim

music structures, limamai (priests) do not attend

dance-hall concerts or participate in the dancing. In Hindu culture,

however, they do, since the dances are part of Hindu rituals

of worship. Other Hindi films

that lend their creative inspiration in the novel’s

dancing scene included

Hatimtai (dir. Homi Wadia, 1956) and Hawa Mahal (dir. B.J. Patel,

1962) with their

elaborate fairytale-ish stories

of mythology and adventure.

Starting in 1976, the local TV station,

NTA Kano, started showing Hindi films at its “late night movies” slots on Fridays.

These films were sponsored by local manufacutirng companies, owned by resident Lebanese merchants, producing

essentially domestic goods – detergents, cleaners, food items, bedding

materials etc – targeted at housewives. Thus a link between Hindi cinema on the small

screen and the domestic space of the Muslim Hausa hold was established. Eventually, since Muslim women were banned

from going to theaters,

houswives partook in the same urban

culture of Hindi cinema as their male counterparts through the small screen

medium of television.

Within a year, and spurred by

advertising returns, more companies had shown interest in sponsoring the screening of Hindi films as

a platform to advertise their products. Thus from 1977 to 2003, Unifoam sponsored the showing of Hindi films on

NTA Kano, while Dala Foods Ltd sponsored the Hindi film screenings from 1982 to 1985. Between

the two of them, the firms made it possible for NTA Kano

to broadcast 1,176 Hindi films through television from October 2nd 1977 when the first Hindi film was shown (Aan Baan), to 7th June 2003.

Hindi

films gained greater

prominence because they were shown not just for a longer period

of time on television, but also on days and times guaranteed to gain

maximum audience attention (Fridays

and weekends). No films from other parts of Africa (e.g. Senegal with its vibrant film culture) were shown; and

other Nigerian features were restricted to the drama series. Ironically enough there was even no attempt by the

Lebanese firms (especially Dala Foods

Ltd and Unifoam Ltd) who sponsored the airing of the Hindi films (and who also distribute them through other subsidiaries) to encourage showing

of the cinema of the Middle East on local channels, especially from

Pakistan or Egypt, the latter of which had a vibrant film culture with which the Hausa could identify with,

especially with the presence of the Egyptian

Cultural Center in Kano. However, as pointed earlier, out that the Lebanese

film distributors in Kano were not mainly

Muslim; and indeed

the few Muslim Lebanese in Kano subscribed to Shi’ite brand of

Islam—which further created a religious spasm between their community and the predominanlty local Sunni community. Consequently, the Lebanese

had no compelling reason to promote

Islamic cinema in Muslim Hausa

northern Nigeria.

Westown inn

To further facilitate this

Hindinization of Hausa entertainment was the repeated plays of songs from popular Hindi films on Hausa

radio request shows targeted at women. Listeners to the programs send greetings to each other and often request for specific songs to be played. The list of the songs played had heavy dosage of Hindi

film and Sudanese

music—along with Hausa

music, giving legitimacy to the view that Hindi,

Sudanese and Hausa

music are all the same. No music from southern

Nigeria is played

in these shows.

Screen to Street—Hausa Adaptations of Popular Hindi Film Music

Hindi films became popular simply

because of what urbanized young Hausa saw as cultural similarities between Hausa social behavior and mores and those

depicted in Hindi films. Further,

with heroes and heroines sharing almost the same dress code as Hausa (flowing saris,

turbans, head covers, especially in the earlier historical Hindi films

which were the ones predominantly shown in cinemas throughout northern Nigeria in the 1960s) young Hausa saw reflections of themselves and their lifestyles in Hindi films, far more than in American films.

Added to this is the appeal of the soundtrack music, the song and dance

routines which do not have ready equivalents in Hausa traditional entertainment ethos. Soon enough cinema-goers started to mimic the Hindi film songs they saw and hear during repeated

radio plays.

Four

of the most popular Hindi

films in northern

Nigeria in the 1960s and which provided

the meter for adaptation of

the tunes and lyrics to Hausa street and popular music were Rani Rupmati,

Chori Chori (dir. Anant Thakur,1956),

Amar Deep and Kabhie Kabhie (dir. Yash Chopra, 1976).

The first of this entertainment cultural leap from screen to street was made by predominantly young boys who, incapable of

understanding Hindi film language, but captivated by the songs in the films they saw, started to use the meter of the

playback songs, but substituting the

“gibberish” Hindi words with Hausa prose. A fairly typical example of street

adaptation was from Rani Rupmati, as transcribed in Table 1.

Table 1 – Itihas Agar Likhna Chaho Transcription

|

Itihaas Agar… (Rani Rupmati) |

English Translation |

Hausa playground version |

Translation |

|

Itihaas agar likhana chaho, |

If the chronicles |

Ina su cibayyo

ina sarki |

Where are the warriors and the King |

|

Itihaas agar likhana chaho |

If the chronicles |

Ina su waziri

abin banza |

Where are the warriors and the King |

|

Azaadi ke mazmoon

se |

of the freedom

of our land are to be recorded |

Mun je yaki mun dawo |

We have been

to the battle and return |

|

(Chor) Itihaas agar likhana

chaho |

(chor) If the chronicles |

Mun samu sandan

girma |

We have come

back with a trophy |

|

Azaadi ke majmoon se |

…of the freedom

of our land are to be recorded |

Ina su cibayyo

in sarki |

Where are the warriors and the King |

|

To seencho apni dharti ko |

Then be ready

to give your

lives |

Ina su wazirin

abin banza |

Were is the Vizier, the

useless cad! |

|

Veeroon tum

upne khoon se |

To your land |

|

|

|

Har har har mahadev |

Let each of us sacrifice ourselves to Mahdeev |

Har har har Mahadi |

Har har har Mahadi |

|

Allaho Akubar |

Allah is the Greatest |

Allahu Akbar |

Allahu Akbar |

|

Har har har mahadev |

Let each of us sacrifice ourselves to Mahdeev |

Har har har Mahadi |

Har har har Mahadi |

|

Allaho Akubar… |

Allah is the Greatest |

Allahu Akbar… |

Allahu Akbar… |

The Hausa translation—which is about returning

successfully from a battle—actually captured the essence of the original song,

if not the meaning which the Hausa could not

understand, which was sung in the original

film in preparations for a battle. The fact that the lead singer in the film and the song, a

woman, was the leader of the troops made the film even more captivating to an audience used to seeing women in

subservient roles, and definitely not in battles.

A further selling point for the song

was the Allahu Akbar refrain, which

is actually a translation, intended

for Muslim audiences of the film,

of Har Har Mahadev, a veneration of Lord Mahadev

(Lord Shiva, the Indian god of knowledge). Thus even if the Hausa

audience did not understand the dialogues, they did identify

with what sounded

o them like Mahdi,

and Allahu Akbar (Allah is the Greatest, and pronounced in the song

exactly as the Hausa pronounce it, as

Allahu Akbar) refrain—further

entrenching a moral lineage with the film, and

subsequently “Indians”. This particular song, coming in a film that opened the

minds of Hausa audience to Hindi

films became an entrenched anthem of Hausa popular culture, and by extension, provided

even the traditional folk singers with meters to borrow.

Thus the second leap from screen to

street was mediated by popular folk musicians in late 1960s and early 1970s led by Abdu Yaron Goge, a resident

goge (fiddle) player in Jos. Yaron

Goge was a youth oriented

musician and drafted by the leftist-leaning Northern Elements

People’s Union (NEPU) based

in Kano, to spice up their campaigns

during the run-up

to the party political campaigns in the late 1950s preparatory to Nigerian independence in 1960 (for more on Abdu Yaron goge and other fiddlers,

see DjeDje 2008).

A pure dance floor player with a troupe

of 12 male (six) and female (six) dancers, Abdu Yaron Goge introduced many dance patterns

and moves in his shows in bars, hotels and clubs in Kano, Katsina, Kaduna and Jos—further

entrenching his music to the moral “exclusion

zone” of the typical

Hausa social structure, and confirming low brow status on his music. The most

famous set piece was the bar-dance, Bansuwai,

with its suggestive moves—with derriere

shaken vigorously—especially in a combo mode with a male and a female dancer.

However, his greatest contribution to

Hausa popular culture was in picking up Hindi film playback songs and reproducing them with his goge, vocals and kalangu [African drum] often

made to sound like the Indian drum, tabla.

A fairly typical example, again from Rani Rupmati, was his adaptation of the few

lines of the song, Raati Suhani, from

the film, as transcribed in Table 2.

Table 2 – Raati Suhani Transcription

|

(Raati Suhani) |

Translation |

Hausa adaptation (Abdu Yaron

Goge) |

Translation |

|

Music interlude, with tabla, flute,

sitar |

|

Music interlude, with tabla simulation |

|

|

|

Mu gode Allah, taro |

People, let’s be grateful to Allah |

|

|

|

Mu gode

Allah, taro |

People, let’s be grateful to Allah |

|

|

Verse 1 |

|

|

|

|

Raati suhani, |

In the beauty of the night |

Duniya da daɗi, |

This world is a bliss |

|

djoome javani, |

My maidenhood gently sways |

Lahira da daɗi, |

The afterworld is also a bliss |

|

Dil hai deevana hai, |

My heart boils with love |

In da gaskiyar ka, Lahira da

daɗi |

If you are truthful, the afterworld will be a bliss |

|

Tereliye… |

Because of you |

In babu gaskiyarka, Lahira da zafi |

If you’re not truthful The afterworld will be hell |

The Hausa lyrics was a sermon to his

listeners, essentially telling them they reap what they sow when they die and go to heaven (to wit, “if you are good,

heaven is paradise, if you are bad, it is hell”).

It became his anthem, and repeated radio plays

ensured its pervasive presence in Muslim

secluded households, creating

a hunger for the original

film song.

In both the adaptations of the lyrics,

the Hausa prose has, of course, nothing to do with the actual Hindi wordings.

However the meter of the Hindi songs became instantly

recognizable to Hausa

audience, such that those who had not seen the film went to see it. Since women were prohibited since 1970s from entering

cinemas in most northern Nigerian cities, radio stations took to playing the records from the popular Hindi

songs. This had the powerful effect of bringing Hindi soundtrack music right into the bedrooms

of Hausa Muslim

housewives who, sans the visuals, were at least able to partake in this

transnational flow of media.

Such popularity eventually found its

way even into Hausa religious space, and Hindi film songs became easily adaptable to local song meters and patterns, especially by religious poets

who were conviced that they can

substitute the Hindi references to Hindu gods in Islamic- themed replacements praising

Prophet Muhammad. In this way, the first to appropriate Hindi film songs were Islamiyya

(modernized Qur’anic schools)

school pupils, who started adapting

Hindi film music.

Some of the more notable

adaptations are listed in Table 3:

Table 3 – Islamic Hindinization of Hindi film soundtrack songs

![]()

Song from Hindi Film Hausa Adapted

Islamic Song

![]() Ilzaam (dir. Shibu Mitra, 1986) Manzon Allah Mustapha [Messenger of Allah,

Ilzaam (dir. Shibu Mitra, 1986) Manzon Allah Mustapha [Messenger of Allah,

Mustapha]

![]() Rani Rupmati (1957) Ɗaha

na Ɗaha Rasulu [Muhammad the Pure] Mother India (dir. Mehboob

Khan 1957) Mukhtaru Abin Zaɓi [Muhammad the Chosen One]

Rani Rupmati (1957) Ɗaha

na Ɗaha Rasulu [Muhammad the Pure] Mother India (dir. Mehboob

Khan 1957) Mukhtaru Abin Zaɓi [Muhammad the Chosen One]

Aradhana (dir.

Shakti Samanta, 1969) Mai Yafi Ikhwana? [What is better than

Brotherhood?]

![]()

The Train (dir. Ravikant

Nagaich 1970) Lale

Da Azumi [Welcome,

Ramadan]

![]()

![]()

![]() Fakira (dir. N.N. Sippy, 1976) Manzo na Mai Girma [My Reverred

Prophet] Yeh Vaada Raha (dir. Kapil Kapoor 1982) Ar-Salu Maceci na [The

Prophet, my savior] Commando (dir. Babbar Subhash,

1988) Sayyadil Bashari

[Leader of the People]

Fakira (dir. N.N. Sippy, 1976) Manzo na Mai Girma [My Reverred

Prophet] Yeh Vaada Raha (dir. Kapil Kapoor 1982) Ar-Salu Maceci na [The

Prophet, my savior] Commando (dir. Babbar Subhash,

1988) Sayyadil Bashari

[Leader of the People]

Qayamat Se Qayamat Tak (dir. Mansoor

Khan. 1988)

Sayyadil Akrami

[Reverred Leader]

![]()

Yaraana (dir. Rakesh Kumar, 1981) Mu Yi Yabon sa Babu Kwaɓa

[Let’s Praise him purely]

Dil To Pagal Hai (dir. Yash Chopra, 1997) Watan Rajab

[The month of Rajab]

![]()

These

adaptations, which were purely vocal,

without any instrumental accompaniment, were principally in the 1980s and 1990s

during particularly religious resurgence in northern Nigeria post-1979 Iranian Islamic revolution which provided a

template for many Muslim clusters to re-orient their entire life towards Islam in Muslim

northern Nigeria. Entertainment was thus adapted to the new Islamic ethos. Thus while not

banning watching Hindi films – despite

the fire and brimstone sermonizing of many noted Muslim scholars – Islamiyya school teachers developed all-girl choirs

that adapt the Islamic messaging, particularly love for the Prophet Muhammad, to Hindi film soundtrack meters. The

basic ideas was to wean girls and

boys away from repeating Hindi film lyrics which they did not know, and which could contain references to multiplicity of gods characteristic Hindu religion.

Having

perfected the system that gets children to sing something

considered more spiritually meaningful than the Hindi words in Hindi film

soundtracks,

structured

music organizations started to appear

from 1986, principally in Kano, devoted

to singing the praises of the Prophet

Muhammad. These groups

– using the bandiri (frame drum) – are usually

led by poets and singers, and

they are collectively referred to as Ƙungiyoyin Yabon Annabi [Groups for Singing the Praises of the

Prophet Muhammad]. The more notable of these in the Kano area include Ushaqul Nabiyyi (established in 1986),

Fitiyanul Ahbabu (1988), Ahawul

Nabiyyi (1989), Ahababu Rasulillah

(1989), Mahabbatu Rasul (1989), Ashiratu Nabiyyi (1990) and Zumratul

Madahun Nabiyyi (1990).

All of these are led by mainstream Islamic poets and rely on conventional methods of composition for

their works, often performed

in mosques or community plazas (Isma’ila 1994). Most are vocal groups, singing a capella, although a few have started to use the bandiri (frame drum) such as Rabi’u Usman Baba, and Yamaha piano-synthesizer, such as Kabiru Maulana,

as instruments during their performances.

The most unique, however, is Ƙungiyar Ushaq’u Indiya [Society for the

Lovers of India] (Larkin 2004).

Although they are devotional, focusing

attention on singing

the praises of the

Prophet Muhammad, they differ from the

rest in that they use the metre of songs from

traditional popular Hausa music and substitute the lyrics of

these songs with words indicating their almost ecstatic

love for the Prophet Muhammad.

However, upon noticing

that Islamiyya school pupils were making hits, as it were, out of Hindi film

soundtrack adaptations,

Ƙungiyar Ushaq’u Indiya quickly changed tack and re-invented itself as Ushaq’u Indiya,

focusing its attention on adapting Hindi film music and substituting the Hindi

lyrics with Hausa lyrics, praising

the Prophet Muhammad.

Notably, the Ushaq’u Indiya singers rely significantly on

onomatopoeia to appropriate equivalent

elements from the Hindi film songs to adapt via Hausa poetics. For example, ‘Kuchie-Kuchie’ from the film Rakshak

became ‘Kuci Muci’ in Hausa [you eat, we also eat]. Like the Hausa shamans who create new translations of the

Qur’an by adapting it into Hausa vocal

amulets, the Ushaq’u Indiya singers and poets also use vocal harmony

to create equivalent renditions of Hindi film songs

in Hausa. These renditions, of course, are not

‘direct’ in the sense that there is no semantic relationship between the Hausa versions and the Hindi originals — in fact Ushaq’u Indiya

were not trying to ‘translate’ the Hindi songs; rather, they exploit the metres and sounds of Hindi songs and

lyrics to publicize their art among

an audience already enamoured with Hindi film songs. Table 4 is a small sample from over 200 Hindi film song

appropriations by the group, based on

intertextual analysis of their archival recordings obtained during fieldwork.

Table 4 – Hindi film appropriation by Ushaq’u Indiya (Lovers of Indiya).

|

Hindi Film |

Film Song |

Ushaqu Indiya Hausa

Appropriation |

|

Rakshak (dir. Ashok

Honda, 1996) |

Koochie – Koochie |

Kuchi Muchi |

|

Rakshak (dir. Ashok

Honda, 1996) |

Sundra – Sundra |

Zahra-Zahra gun ki nazo bara |

|

Yash (dir. Sharad

Saran, 1996) |

Subah-Subah Jab kirki kole |

Zuma-Zuma mai garɗi |

|

Lahu ke do Rang (dir.

Mehul Kumar, 1997) |

Hasino Ko Aate Hai |

Hassan da Hussain Jikokin Nabiy

na |

|

Dil (dir. Indira

Kuma, 19900 |

Humne Ghar Choda

Hai |

Manzon Allah Ɗahe |

|

Anari (dir. Hrishikesh Mukherjee, 1959) |

Diwana me Diwana |

Rasulu Abin dubana |

|

Kala sona (dir.

Ravikant Nagaich, 1975) |

Se Sun Sun

Kasam |

Sannu Mai Yassarabu ɗan Kabilar Arabu |

|

Coolie No 1 (dir. David

Dhawan, 1995) |

Goriya churana mera

jiya |

Godiya muke wa sarki ɗaya |

|

Ragluveer (dir. K. Pappu, 1995) |

O Jaanemann Chehra Tera |

Na zo neman

tsari ceto |

|

Johny I love

you (dir. Rakesh

Kumar, 1982) |

Kabhi-Kabhi Bezubaan Parvat Bolate |

Kabi – kabi Annabi mu in ka ki shi za ka sha

wuya |

|

Boxer (dir. Raj N. Sippy,

1984) |

Janu Na jaane kab se Tujhko

pyar |

Yanu-na yanu na ba wani

tamkarka |

|

Hum (dir. Mukul

S. Anand, 1991) |

Jumma Chumma

Dede |

Zuma- zumar bege mun sha |

|

Abe Hayat (dir.

Ramanlal Desai, 1955) |

Main gareebon ka dil hoon |

Na gari mu ke yabo Shugaban Al’umma |

|

Shaan (dir. Ramesh

Sippy, 1980) |

Janu meri jaan metere

kurbaan |

Jani – babuja ba tamkar

kur’an |

Like all the other songs in their

repertoire, the songs are not based on attempts to translate the original meanings of the titles of the

Hindi film songs; rather refrains, chorus, and main lines are identified and their Hausa substitutes used in

rendering the original song. Thus the double meaning

of ‘interpretation’ (Newmark

1991, 35), which is both the technical

term for spoken translation but also hints at the

act of transformation that occurs in the example I have given here, comes to

the fore in the Ushaq’u Indiya singers’ translations of Hindi film songs.

The Hausa youth obsession with Hindi

language and culture was further illustrated by the appearance, in 2003 of what was possibly the first Hausa-Hindi language primer in

which a Hausa author,

Nazeer Abdullahi Magoga

published Fassarar Indiyanchi a Saukake —

Hindi Language Made Easy as shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 – Hausa-Hindi Phrase Books

The

author is pictured

wearing Hausa cap among Bollywood super stars on the covers

of the books. Like most Hausa, the author equates “Hindi” with Indian, not acknowledging that India is a political expression comprising many ethnic

and language groups.

For instance, 14 languages

are mentioned in the constitution of India. There is thus no singular “Indian” language

as such., much as there is no singular “Nigerian” language.

These books become all the more

significant in that they are the first books in Hausa language that show the vivid

effects of media

parenting. It is thus through

the books that we learn the meanings of some of the titles

of 47 popular Hindi films such as Sholay (Gobara,

fire outbreak), Kabhi-Kabhie (wani sa’in, other times), Agni Sakshi (zazzafar shaida, strong

evidence), Darr (tsoro, fear), Yaraana (abota,

friendship), Dillagi (zaɓin zuciya, heart’s choice), Maine Pyar Kiya (na faɗa

cikin soyayya, fallen in love) and others. Volume 1 also contains the complete transliteration of

Hindi lyrics translated into Romanized Hausa, of Maine Pyar Kiya and Kabhi-Khabie.

Magoga started

working on the first volume, Fassar Indiyanchi in

1996, and when the Hausa

video film boom started in 2000 he published the book. He has three others planned;

a second volume of the books in which takes the

language acquisition to the next level—focusing on culture and customs of India (or more precisely, Hindu). The

other two books, still planned are

“song books”, Fassarar Waƙoƙin Indiya (Translations

of Hindi Film Songs) in two volumes.

In an interview I held with Magoga on March 19, 2004 in Kano, northern

Nigeria, the author

narrated how he became deeply interested in learning the Hindi language

from watching thousands of Hindi films,

and subsequently conceived of the idea of writing

a series of phrase books on Hindi language. In 2005 he was

given a one-hour slot on Radio Kano FM during

which he presents Mu Kewaya Indiya

[let us visit India], a program in which he translates Hindi film songs into Hausa. His fluency

in Hindi language

was such that in 2007 it attracted

BBC World Service,

London, which held a live-on-air interview with him about his life with an

Indian journalist, Indu Shekhar Sinha, in Hindi. This attracted so much

attention in India that the BBC

Delhi office sent a crew to interview Magoga in Kano in July 2008. The crew was led by Rupa Jha who recorded

the entire interview

in Hindi language

at the Tahir Guest Palace hotel in Kano and which was

broadcast in India. Subsequently Magoga became a singer in Kano, holding concerts (‘majalisi’) during which he

sings the praises of venerated Sufi saints

as well as local politicians in Hindi (often dressing in Indian clothes).

He was also given a slot at

Farin Wata, an independent Television Studio in Kano during which he presents a ‘request program’ in which

viewers request for historical details of a particular film and request

a particular song. The screen

shots in Fig. 2 shows how Magoga

dresses for the part.

Fig 2. Nazeer Magoga Presenting ‘Bollywood Stan’ in a Local

TV Studio

By 2012 Magoga has been given a series

of slots in various radio and TV stations across northern Nigeria where he translates Hindi lyrics into Hausa and

holds continuous fluent conversation

in Indi with phone-in listeners. He also became a singer, releasing an album in September 2012 which contain various

Islamic devotional and political songs in Hausa and Hindi.

Hausa Appropriations of Popular Hindi Film Music

Hindi films became popular simply

because of what urbanized young Hausa saw as cultural similarities between Hausa social behavior and mores and those

depicted in Hindi films. As Brian Larkin

(2004, 100) noted,

Many

Hausa, for instance, argue that Hausa and Hindi are descended from the same

language—an argument also voiced to me by an Indian

importer of films

to account for their popularity. While wrong in terms of linguistic evolution, this

argument acknowledges the substantial presence of Arabic and English loanwords in both languages, a key

factor in creating this perceived sense of similarity and which helps many Hausa “speak Hindi.”

Bettina David (2008) records similar

observations about the cultural relationships between Hindi films and Indonesian public culture, where she notes that

for many Indonesians, “Bollywood still seems to represent something

similar to their own culture

in being distinctively non-Western.” (183).

Further, with heroes and heroines sharing almost the same dress code as Hausa (flowing saris, turbans,

head covers, especially in the earlier historical Hindi films which were the

ones predominantly shown in cinemas

throughout northern Nigeria in the 1960s) young Hausa saw reflections of themselves and their lifestyles in Hindi films,

far more than in American

films. Added to this is the appeal of the soundtrack music, the song and dance routines which do not have ready

equivalents in Hausa traditional entertainment ethos. Soon enough cinema-goers started to mimic the Hindi film songs

they saw. The next nexus of Hausa popular culture to adopt the Hindi film format therefore was the Hausa

video film.

Screen to Screen – the Hausa Video Film Soundtrack

Hausa video films as a major

entertainment focus started with the production of the first Hausa film on cassette in March 1990. It was Turmin Danya (dir.

Salisu Galadanci). The first Hausa video films from 1990 to 1994

relied on traditional music ensembles to compose the soundtracks, with koroso music

predominating. The soundtracks were just that – incidental background music to accompany the film,

and not integral to the story. There was often

singing, but it is itself embedded in the songs, for instance during

ceremonies that seem to feature in

every drama film. However, the availability of the synthesizer keyboards such

as the Casiotone MT-140 and Yamaha

PSR, as well as pirated music making software such as FruityLoops Reason 3.0, and editing software such as Cool Edit

and Adobe Audition, the Hausa video

film acquired a more transnational pop focus and outlook creating what I call Hausa Technopop music – a genre of music

that departed considerably from its antecedent

African acoustic roots, and embraced Hindi film melodies exclusively, if

retaining Hausa language lyrics.

This follows a

trajectory similar to the evolution of Indonesian popular music, dangdut, “a hybrid pop music extremely popular among the lower classes that

incorporates musical elements from

Western pop, Hindi film music, and indigenous Malay tunes” (Bettina David 179). In Indonesia Hindi films were

shown after independence in 1945 as entertainment for Indian troops that were part of the English contingent.

Subsequently, the films were shown massively

on local television and thus the eventually served as a model for the

development of Indonesian films – just as the Hausa video

filmmakers adopt Hindi film templates in their films, in addition to appropriating many Hindi films directly into Hausa language

versions.

While a lot of the songs in the Hausa

video films were original to the films, yet quite a sizeable are direct

appropriations of the Hindi film soundtracks – even if the Hausa main film

is not based on a Hindi film. This, in effect means a Hausa video film can

have two sources of Hindi

film “creative inspiration” – a film for the storyline (and fight sequences), and songs from

a different film.

Table 5 lists the Hindi inspirations for few of the 128 Hausa video films appropriated from Hindi films. This was

based on analysis of 615 Hausa home videos and

discussions with producers, cast, crew and editors from 2000 to 2003

during fieldwork for a larger

study.

Table 5 – Inspirations from the East:

Hindi as Hausa

Film Songs

|

Hausa Film |

Playback Song |

Hindi Film |

Playback Song |

|

Hisabi |

Zo Mu Sha

Giya |

Gundaraj (dir. Guddu

Dhanoa, 1995) |

Mena Meri Mena Meri |

|

Alaqa |

Duk Abin

Da Na Yi |

Suhaag (dir.

Balwant Bhatt,1940) |

Gore Gore Gore Gore |

|

Alaqa |

Sha Bege |

Mann (dir.

Indra Kumar, 1999) |

Mera Mann |

|

Darasi |

Tunanin Rai Na |

Mann (dir.

Indra Kumar, 1999) |

Tinak Tini

Tana |

|

Farmaki |

Suriki Mai Kyau |

Kabhi Khushi

Kabhie Gham... (dir.

Karan Johar, 2001) |

Surat Huwa Mat Dam |

|

Hisabi |

Don Allah Taho

Rausaya |

Angrakshak (dir. Ravi Raja Pinisetty, 1995) |

Ham Tumse Na Hi |

|

Shaida |

Na Fi Ki Yi Haƙuri |

Darr (dir.

Yash Chopra, 1993) |

Jadoo Tere

Magal |

|

Laila |

Laila Laila Laila |

Zameer (dir.,

Ravi Chopra, 1975) |

Lela Lela Lela |

|

Gudun Hijira |

Ga Wani Abu Na Damun

Shi |

Josh (dir. A Karim, 1950) |

Hari Hari Hari |

|

Aniya |

Gamu Mu Na Soyayya |

Josh (dir.

A Karim, 1950) |

Hari HariHari |

|

Gudun Hijira |

Ina Ka ke Ya Masoyi

Na |

Mast (dir. Ram Gopal Varma,

1999) |

Ruki Ruki |

|

Gudun Hijira |

Gudun Hijra |

Dhadkan (dir. Dharmesh Darshan, 2000) |

Dil Ne He Ka Ha He Dil

Se |

|

Ibro Dan Indiya |

Sahiba Sahiba |

Rakshak (dir.

Ashok Honda, 1996) |

Sundara San |

|

Tasiri 2 |

Kar Ki Ji Komai |

Wardaat (dir. Ravikant Nagaich, 1981) |

Baban Jayi |

|

UmmulKhairi |

Ina Wahala |

Mohabbat (dir.

Reema Rakesh Nath,

1997) , |

Mohabbat Ti He |

|

Kasaita |

Ni Na San Ba Ki Da Haufi |

Major Saab (dir.

Tinnu Anand, 1998) |

Ekta He Pal Pal Tumse |

|

Darasi |

Duk Girma

Na Sai Kin Sa Na Yi |

Hogi Pyaar

Ki Jeet (dir.

P. Vasu, 1999) |

Ho Dee Bana |

|

Taqidi |

Ni A’a |

Ayya Pyar |

Jodi Pyar |

|

Al’ajabi |

Ayyaraye Lale |

Ram Balram

(1980) |

Ka Ci Na Gari Mil Gay |

|

Jazaman |

Ai Na San Mai

So Na |

Lahu Ke Do Rang

(1997) |

Awara Pagal

Dibana |

There is a radical difference in the

translation styles used between Ushaqu and Hausa video filmmakers. Whereas the Ushaqu singers

attempt a poetic

vocal harmony between

the source sound and treating

it as text, and target sound, Hausa video filmmakers use only the musical harmonies of the source

sound, ignoring its textual properties. In fact in my repertoire of over 50 re-renderings I could locate

only one track

from the Hindi

film, Zameer (dir. Ravi Chopra, 1975) which had onomatopoeic property with its corresponding Hausa version, as highlighted in Table 5. Leila/Layla are both common female names among Muslim Hausa. In a

way, therefore, the Hindi film songs in Hausa video films are cover versions

rendered locally. The originals

do not simply disappear because a local one is available—for the purpose was not to displace the transnational originals; but to prove prowess in copying the transnational songs.

The Hindi originals are increasing becoming

available on DVDs stuffed with often over 100 songs in MP3 format and sold for less

than US$1 if one bargains hard enough from street media vendors selling

them in push carts and wheel barrows.

Thus besides providing templates for

storylines, Hindi films provide Hausa home video makers with similar templates for the songs they use in their

videos. The technique often involves picking

up the thematic elements of the main Hindi film song, and then substituting with Hausa lyrics—creating translation equivalency. Consequently, anyone familiar with the Hindi film song element will easily

discern the film from the Hausa home video equivalent. Although this process of adaptation is extremely success because the video film producers

make more from films with song and

dances than without, there are often dissenting voices about the intrusion of the new media technology into the film

process, as reflected in this letter from a correspondent:

I

want to advise northern Nigerian Hausa film producers that using European music

in Hausa films is contrary to

portrayal of Hausa culture in films (videos). I am appealing to them

(producers) to change their style. It

is annoying to see a Hausa film with a European music soundtrack. Don’t the

Hausa have their own (music)?...The

Hausa have more musical instruments than any ethnic group in this country, so why can’t

films be produced

using Hausa traditional music? Umar Faruk Asarani, Letters

page, Fim, No 4, December 1999, p. 10. (My translation of original Hausa language source).

Interestingly, other musical sources

are often used as templates. Thus a Hindi film template can often have songs borrowed form a totally different source.

Ibro Ɗan Indiya (pr. Nasiru ‘Dararrafe’ Salisu, 2002) for instance,

with had an adaptation of a song from Mohabbat (1997, dir. Reema Rakeshnath) contains an adaptation of a composition by Oumou Sangare,

the Malian diva, Ah Ndiya (Oumou

Sangare 2003). This was appropriated as “Malama Dumbaru” in the Hausa video

film version, and remains the only African

rendering that I am aware

of.

Conclusion

In this paper I looked at three styles of vocal performances in the domestication of transnational source

text into Hausa.

The first was the onomatopoeic use of selected

Qur’anic texts by Hausa

shamans for their public culture clients who seek cure for one problem or other. In the second and third instances,

this provided a ready template for the use of both onomatopoeia and equivalence as translation devices by purveyors

of the Hausa popular culture industries in musical performances and video films in their appropriation of transcultural

entertainment products, which they rework for their local clients. However, a transitory route was via official

translation of selected Middle Eastern stories into Hausa language—thus conferring on Hausa popular culture

a transcultural base.

In trying to determine what constitutes global culture, John Tomlinson (1999, 24) argues that

The

globalised culture that is currently emerging is not a global culture in any

utopian sense. It is not a culture

that has arisen out of the mutual experiences and needs of all of humanity…It

is, in short, simply the global extension of Western culture.

The problem with this view, as argued

by J. Macgregor Wise (2008, 35) is that it assumes that

the

process of globalization is a one-way flow: from the West (read: America) to

the rest. Especially in the 1970s,

media scholarship supported this view, giving evidence of how the West

dominated the global film and

television industries as well as the international news services such as the

Associated Press and Reuters…It also assumes that this process

is uniform and occurs in the same way everywhere. That is, it assumes that the

world will become homogenized, that it will look the same wherever

you go.

However, there are other mediascapes

besides Western. In South America, the Brazilian Telenovelas were spectacularly successful within not only South

American continent, but also across

the world. As Benaivdes (2008,

2) suggested,

It

is a testament to the telenovela’s success that many of the plot lines are

reused or that a telenovela will be rebroadcast in different countries

after being adapted to their national language

and cultural

configuration.

This transnational element is only heightened by the

incredible export success of telenovelas throughout the Americas

(including the United States) and all over the world. Latin American telenovelas have been exported,

with extraordinary cultural implications, to Egypt, Russia, and China, as well

as throughout Europe.

In a similar way, Hindi films have

provided powerful alternatives of imagined realities to Western mediascape (e.g. Vasudevan 2000, Kripalani 2005,

Mehta 2005, Larkin 2003). Thus, for many

non-Western countries,

Over the decades, Hindi films emerged

as an accessible, visual and ideological alternative to prescriptive,

evolutionary patterns of development advocated by some Hollywood films and

other select First World countries. (Shresthova, 13).

In Indonesian popular culture,

Contemporary

Indonesian public culture increasingly reorients itself, looking to other

non-Western social, cultural, and

religious forms as alternatives in the struggle to define a modern identity

without becoming totally

“Westernized.” (David, 195).

In Africa, the Nigerian film industry,

Nollywood, has emerged in recent years as a powerful pan-African film industry not only in the individual countries of Africa, but in Black diaspora (see for instance, Ebewo 2007, Haynes,

2000, Haynes and Okome 1998, McCall 2004, Offord

2009, Omoera 2009, Postcolonial Text,

“Nollywood: West African Cinema,” Vol 3, No

2, 2007, and Film International #28,

“Welcome to Nollywood: Africa Visualizes,” August 1, 2007).

Consequently, as Arjun Appadurai (1996)

also argued, globalization is not a single process happening everywhere in the same way. Thus globalized culture

does not always have to mean Western culture, especially as the influence does not have to be vertical (from North to South), but could also be horizontal (from South to South). In northern Nigeria,

as indeed in other countries

sharing similar postcolonial experiences, the transcultural flow is in a different direction. It is this

multidirectional flow of transnational media influences that see the ready translation—using as many

devices as possible—of transnational popular culture into Hausa urban public culture.

References

Abdullahi, A.G.D., 1978, ‘Tasirin Al’adu da Ɗabi’u iri-iri a

cikin Tauraruwa Mai Wutsiya’[Foreign

influences in Tauraruwa Mai Wutsiya [The comet]. Proceedings of the First International Conference on Hausa Language and Literature, held at

Bayero University, Kano, Nigeria, July 7-10, 1978. Kano, CSNL. Kano, Center for the Study of Nigerian

Languages.

Appadurai, Arjun., 1996, Modernity

at Large: Cultural

Dimensions of Globalization. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minneapolis Press.

Baker, Mona., 1992, In Other Words: a Coursebook on Translation, London: Routledge.

Benavides, O. Hugo., 2008,

Drugs, Thugs, and Divas:

Telenovelas and Narco-Dramas in Latin America.

Austin: U of T Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 1969. The

Task of the Translator, translated by Harry Zohn, in Illuminations: Essays and Refkections, ed. with introduction, Hannah Arendt, 69–82.

New York: Schockenbooks.

Bredin, Hugh.,

1996, Onomatopoeia as a figure and a linguistic principle. New Literary History, 27, no. 3: 555

– 69.

Catford, John C., 1965, A

Linguistic Theory of Translation: an Essay on Applied Linguistics, London:

Oxford University Press.

David, Bettina., 2008,

“Intimate Neighbors: Bollywood, Dangdut Music, and

Globalizing Modernities in Indonesia.”

In Global Bollywood: Travels of Hindi

Song and Dance, eds. Sangita Gopal and Sujata Moorti. Minneapolis:

UM Press: 179-199.

DjeDje, Jacqueline C. 2008, Fiddling in West Africa:

Touching the Spirit

in Fulbe, Hausa,

and Dagbamba Cultures. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Ebewo,

Patrick J., 2007, “The Emerging Video Film Industry in Nigeria: Challenges and

Prospects.” Journal of Film and Video. 59: 3, 46-57

(Fall 2007).

Haynes, Jonathan

and Okome, Onookome., 1998, “Evolving Popular

Media: Nigerian Video Films” Research in African Literatures, Vol. 29, No. 3

(Autumn, 1998): 106-128.

Haynes, Jonathan., 2000, Nigerian Video Films: Revised Edition. Athens: Ohio University Research in International Studies Series. 2000.

Haynes,

Jonathan., 2006, “Political Critique in Nigerian Video Films.” African Affairs, 105/421, 511–533. Hervey, S., Higgins, I., and Haywood,

L. M., 1995, Thinking Spanish Translation: A Course in Translation

Method: Spanish

into English. London;

New York: Routledge.

House, Juliane.,

2002, A Model for Translation Quality

Assessment. Tübingen: Gunter

Narr.

Ishwar Modi, et al 2002,

Theatrical Traditions in India, a chapter written

for UNESCO "Theatre across Cultures: Encounters along the Silk Road". Paris,

Unesco.

Isma’ila, Aminu., 1994, ‘Rubutattun Waƙoƙi a Ƙasar Kano:

Nazarin Waƙoƙi Yabon Annabi (SAW)” (Written Poetry in Kano: A Study of the Poems of

the Praises of the Prophet Muhammad (peace and blessings of Allah be upon him). Unpublished B.A. (Hons)(Hausa)

undergraduate dissertation, Department of Nigerian Languages, Bayero University, Kano.

Jakobson, Roman., 1959, 'On Linguistic Aspects

of Translation', in On Translation, ed. R. A. Brower.

Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press: 232-39.

Kripalani, Manjeet., 2005, The Business

of Bollywood. In India Briefing: Takeoff

at Last?, ed. Alyssa Ayes and Philip

Oldeburg. Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe: 171-188

Larkin, Brian., 2003, “Itineraries of Indian Cinema.

African videos, Bollywood

and Global Media.”

In, Multiculturalism, Postcolonialism and Transnational Media, eds.

Ella Shohat and Robert Stam. New Brunswick: Rutgers

University Press: 170-192.

Larkin, Brian., 2004, ‘Bandiri Music, Globalization, and

Urban Experience in Nigeria’. Social Text

81, Vol. 22, No. 4, Winter 2004, 91-112.

Macnaghten, W. H., and Henry Whitelock Torrens., 1838, The book of the thousand nights and one

night: from the Arabic

of the Aegyptian m.s. Calcutta:

W. Thacker & Co.

Malumfashi, Ibrahim., 2009. Adabin Abubakar Imam (Abubakar

Imam’s literature). Sokoto (Nigeria): Garkuwa Media Services.

McCall, John Christensen., 2005,

"Nollywood Confidential: the unlikely rise of Nigerian

video film." Transition Magazine. Du Bois Institute, Harvard University. 2004, 95. 98-109.

Mehta, Monika.,

2005, “Globalizing Bombay

Cinema: Reproducing the Indian State

and Family.” Cultural Dynamics, Vol. 17, No. 2, 2005.

135-154.

Newmark, Peter. 1991. About translation. Clevedon

[England]: Multilingual Matters.

Nida, Eugene A., and Charles

R. Taber. 1969. The theory and practice of translation. Leiden:

E. J. Brill.

Offord,

Lydia D., 2009, “Straight outta Nigeria: Nollywood and the emergence of

Nigerian video film (theory). Lost and Turned Out (production).” M.A. thesis, Long Island University, The Brooklyn Center,

2009.

Omoera,

Osakue Stevenson., 2009, “Video Film and African Social Reality: A

Consideration of Nigeria-Ghana Block of West Africa.”

J

Hum Ecol, 25(3):

193-199 (2009).

Palmer, H. Richmond, 1908, Kano Chronicles. (Tarikh

Arbab Hadha al-balad

al-Musamma Kano). Journal of Royal Anthropological Institute 38: 59 – 98.

Sa’id, Bello., 1997, Kwatanci-Faɗi: Tasirin

Harshe A Tsibbun Bahaushe [Sound alike in Hausa Shamanism].

Harsunan Nijeriya

Vol. XVIII:

Shresthova,

Sangita. 2008. Between Cinema and Performance: Globalizing Bollywood Dance. PhD

thesis, University of California.

Tomlinson, John., 1999, Globalised

Culture: The Triumph of the West? In Sketon, Tracy and Tim Allen (eds.)

Culture and Global Change. London: Routledge: 23-31.

Vasudevan, Ravi S., 2000,

Making Meaning In Indian

Cinema. Delhi: Oxford

UP. 2000.

Vinay, J.P. and J. Darbelnet., 1995, Comparative

Stylistics of French and English:

a Methodology for Translation,

translated by J. C. Sager and M. J. Hamel. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John

Benjamins. 1995.

Wise, J. Macgregor., 2008, Cultural Globalization: A User’s Guide. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

0 Comments

ENGLISH: You are warmly invited to share your comments or ask questions regarding this post or related topics of interest. Your feedback serves as evidence of your appreciation for our hard work and ongoing efforts to sustain this extensive and informative blog. We value your input and engagement.