Cite this article as: Ago, A.S. (2023). Morphophonological Study of Southern Bade Prefixes. Tasambo Journal of Language, Literature, and Culture, (2)2, 1-10. www.doi.org/10.36349/tjllc.2023.v02i02.001.

Adamu Ago Saleh

Department of African Languages and Cultures

Ahmadu Bello University Zaria, Nigeria

adamuago@gmail.com

+2348069513160

Abstract

This paper describes the structures and functions of prefixes in southern Bade, a dialect of Bade language. Bade is the West Chadic-B language of Afro-Asiatic phyla, mainly spoken in the northern part of Yobe State, Nigeria. Prefixation, as a morphological operation, is a process whereby a bound morpheme is attached before a root or a stem to derive a new lexeme or inflect the existing one. In addition to the researcher’s innate knowledge as a native speaker, the data were obtained through an oral interview and unobtrusive observation, mainly from dialect speakers of the language. Generative Approaches (Chomsky and Halle, 1968) formed the theoretical framework of the study. From the data obtained, the paper identified and discussed five derivational prefixes found in the nominal system of the dialect {ma-} prefix is used in deriving agential nouns, personal and instrument names, {ga(a)-} in forming participial adjectives and adverbs, {saa-} in deriving female namesake and circumstantial names. {tə-} and {də-} are used in deriving personal names and adjectives respectively from a verb base. The morphophonological alternations that occurred in the prefixation processes include the weakening of voiced velar /g/ to becoming labial velar [w]; schwa [ə] deletion re-syllabification; insertion of link element; deletion, labialization; and palatalization. It argues that some of the prefixes simultaneously co-occur with varying suffixes, depending on the word class derived, in the formation process, while a few are not.

Keywords: Bade, Bound morpheme, Derivation, Generative, Prefixation

Bade is one of the seven languages of the West Chadic languages indigenous to Yobe State. The others are Bole, Ɗuwai, Karekare, Maka, Ngamo, and Ngizim. Specifically, the language is dominant in two local governments, Bade and Jakusko. The language relatives closest to Bade are Ngizim, spoken in the south, around Potiskum, and Ɗuwai, spoken in the east of Gashua (cf. Greenberg 1963, Newman, 1977, Schuh, 1975, 1978, 1981). There is considerable variation in Baden speakers with practically every village having its peculiarities. Ziegelmeyer (2011:1) pointed out that Bade, “is dialectally very diverse, to the extent that one could speak of several Bade languages." However, three main dialects have been identified, namely Western, Southern and Northern which comprise Gashua/Eastern and central Bade (Schuh, 1981, 2007). Therefore, this paper is to discuss only the morphophonological alternations found as a result of the prefixation in Southern Bade.

Morphophonology and Prefixation

The morphophonological analysis is considered such that both phonology and morphology are governed by morphophonological alternating rules (Olga, 1971:69). Hooper (1976) further notes the difference between alternations, which are phonological in nature, and those purely morphological. The ultimate purpose of morphophonology is to discover and formulate the rules for the transformation of phonological sequences into morphological ones within and across a morpheme boundary (cf. Olga, 1971:69). This is further supported by Al-Hassan (1998:105) where he remarks that morphophonological change can either be segmental or suprasegmental one. Derivational morphemes are affixes used to either change or maintain a grammatical class of words to which they are attached. For such cases of derivation that changes the grammatical class of words, the terms denominal (derived from a noun), deverbal (derived from a verb) and deadjectival (derived from an adjective) are in general use (cf. Haspelmath and Sims, 2010:87).

Schuh (2007) identified three derivational prefixes and one inflectional in his study of the nominal and verbal morphology of Western Bade. The derivational prefixes identified are {ma-} which is used to derive nouns mostly, from a verb-stem. For instance agential noun (mabənaan, mabəænən < bənu ‘cook’macaptaan, < caæptu ‘one who collects) and instrumental (marbəcən < ərbəcu ‘key’, mazəɗaan < zəɗu ‘digger, digging stick). Also {ma-} is used to derive locative noun s (makfaan (m) < əkfu ‘entrance’, magvaan < əgvu ‘door of a compound) and ordinal nouns (masərənu < sərən ‘second’, makwanu < kwan ‘third’). The two other derivational affixes are prefix {ga-} and {də-} which are also discussed by Ziegelmeyer (2011) while describing Gashua Bade adjectives. The prefix {ga-} is used to derive participial adjectives and descriptive nouns; while the prefix də- can be added to verb roots to derive stative resultatives as in dəva < vo' ‘shot’ and dəgda < əgdu ‘snapped off’. The inflectional prefixes {a-} and {də-}, are used in forming imperative verbs. Following Schuh (2007) and Ziegelmeyer (2009a), Ago (2020) discusses the prefix {a-} as an imperative marker in the verbal system of Bade. He observes morphophonological alternations such as consonant weakening, diphthongization, labialization, nasal backing and monophthongization, that were triggered by prefixation of the imperative marker. However, none of these works addresses the Southern Bade prefixes, which is the purpose of this paper.

Methodology and Theoretical Framework

The primary data collected as part of this study was field research, which the researcher obtained from several Southern Bade native speakers that were selected using a purposive sampling technique. Respondents' answers were recorded on paper and tape-recorded at the same time with their permission. Then, using the native speaker's intuition, and linguistic recognition, the data is validated and analyzed. The generative approach is used as a theoretical framework in the analysis of the data for this research. The theory can be traced back to Chomsky and Halle (1968). Generative phonology posits two levels of phonological representation; an underlying and phonetic representation. The underlying representation is in the basic form of a word before any phonological rules are applied to it. The phonetic representation, on the other hand, is that form of a word that is derived when phonological rules are used and surfaced as spoken. However, phonological rules map underlying representations of phonological representations using morphophonological rules such as the deletion, insertion or modification of segment characteristics (cf. Schane 1973, Abubakar 1983, Baba 1988, and Sani 2011).

Southern Bade Prefixes

Five (5) prefixes are used in creating new words in Southern Bade namely, {ma-} {ga-}, {saa-}, {tN-}, and {dN-}. Each of these prefixes is discussed below accordingly.

This study observed three different noun formations by prefixing {ma-} morpheme to a verb stem or non-verb stem. These include agential nouns, instrument nouns, and personal names. The agential noun is derived, for instance, by adding an H-tone {ma-} prefix to a verb stem, as in Table 1.

Table 1: {ma-} Prefix

| Base | Prefix + Base | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /dàwu/ | /ma- + dàwu/ | [madàwu] | Herd |

b. | /gùɗu/ | /ma- + gùɗu/ | [mawùɗu] | Hast |

c. | /ʧàptu/ | /ma- + ʧàptu/ | [maʧaptu] | To collect |

d. | /ɗàlmu/ | /ma- + ɗàlmu/ | [maɗalmu] | To repair |

e. | /tàkNmu/ | /ma- + tàkNmu/ | [matakəmu] | To begin |

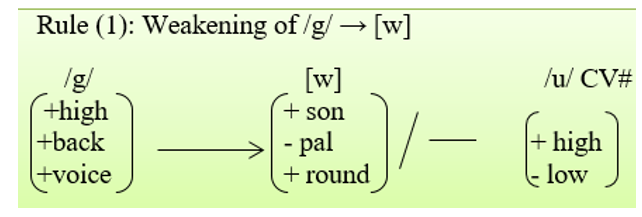

Morphologically, it is observed that there is an addition of syllables in the derivatives. The tone pattern of (1a&b) is HLH, which has CV syllable medially, while (1c-e) is HHH as having CVC in the word-medial position. In the case of example (1b), the prefixation of agential marker {ma-} to verb-base [gùɗu] triggered the weakening of the voiced velar /g/ to become labial velar [w], and then the derivative surfaced as [mawùɗu]. The rule accounting for /g/ weakening is therefore formulated as thus:

Rule 1 states that voiced velar /g/are weakened to [w] before the high back vowel /u/ in the penultimate syllable.

In another instance, while deriving a noun of the instrument, as can be seen in examples (2) below, the schwa sound of the verb-base /NrbNʧu/ ‘to open’, and /Nzvàvìju/ ‘to sprinkle’, is lost.

Table 2: Example 2

| Base | Prefix + Base | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /NrbNʧu/ | /ma-+NrbNʧu/ | [marbNʧu] | key |

b. | /Nzvàvìju/ | /ma-+Nzvàvìju/ | [mazvàvìju] | Small calabash |

The schwa deletion is caused by the influence of the low vowel /a/ attached to it thereby forming a CVC syllable with the hin morpheme boundary. However, the suffix of the base is left unchanged. The rule for deletion of /ə/ in this regard is formulated thus:

The above rule states that the schwa sound is deleted when preceded by a low vowel in a closed syllable.

The third noun derivation through {ma-} prefixation is a personal name. In deriving the name of a person, {ma-} is prefixed to a verb and/or noun base, while the final vowel of the base is substituted with /a/. Here are examples in (3):

Table 3: Example 3

| Base | Prefix + Base | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /Nskùnu/ | /ma-+Nskùnu/ | [màskwunà] | Person name |

b. | /ɮàru kuwa/ | /ma-+ɮàru kuwa/ | [màɮàrkwuwà | snake fighter |

c. | /dNba/ | /ma-+dNba/ | [màdǝbà] | rich |

In (3a) above, the initial sound of the verb is dropped, while the final vowel of the verb stem is replaced with the/-a/ suffix. In (3b), as the {ma-} prefix attached to verb-based compound nouns, the /u/ sound of the verb /ɮàru/ is deleted leaving a CVC syllable then added to noun /kuwa/ ‘snake’. The word for ‘rich’ ‘madǝba’ is derived from a nominal base dNba ‘gotten’ which is a combination of an adverbial marker {dN-} prefix, and verb bo ‘found’. The vowel /o/ of the verb bo is deleted living adverbial suffix {-a}.

Within the sound system of Bade in general, velar sounds /k, g/ found in the environment before round vowels /u, o/ are realized as [kw, gw]. It is an automatic morphophonological process whereby high back rounded vowel /u/ influences plain velar sounds /g, k/ that follow it within or across morpheme boundaries to become labialized velars [gw, kw]. The following examples show how these round vowel sounds motivated the addition of lip rounding to velars.

Table 4: Example 4

| UR | SR | Gloss |

a. | /maskuna/ | → [màskwunà] | Person name |

b. | /maɮarkuwa/ | → [màɮàrkwuwà] | snake fighter |

c. | /maguru/ | → [màgwurù] | jealous |

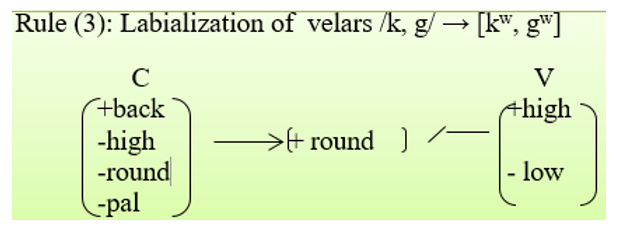

In examples (4) above, velars /g, k/ acquired the feature value of high back vowel /u/ following them and automatically become [gw, kw]. Therefore, the labialization rule is formulated thus:

The rule states that plain velar /k, g/ is realized as labialized in the environment before a high back rounded vowel.

Many lexical items are derived through prefixing {ga-} to a base form followed by {-aki} suffix in Southern Bade. Consider the following examples in (5) below:

Table 5: Example 5

| Base | Prefix + Base | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /bàku/ | /ga-+bàku+-aki/ | [gàbàkakji] | roasted |

b. | /nàwu/ | /ga-+nàwu+-aki/ | [gànàwakji] | cooked |

c. | /mbòotu | /ga-+mbòotu+-aki/ | [gàmbòotakji] | Short |

d. | /ʧNkpàpu/ | /ga-+ʧNkpàpu+-aki/ | [gàʧNkpàpakji] | Squat |

e. | /kùru/ | /ga-+kùru+-aki/ | [gàkwùrakji] | displeased |

As observed in example (5) above, in the derivation of the adjectives, the final vowel of the base is deleted when the {-aki} suffix is attached to the base. The {-aki} suffix serves as a nominalizer and thereby forms masculine adjectives. Here, we observed the rule for deletion as follows:

The rule says that a high back rounded vowel is deleted before {aki} suffix.

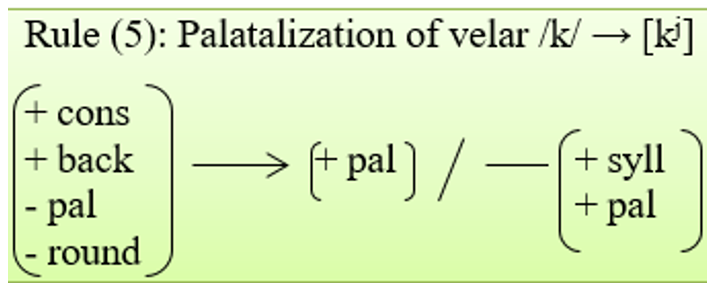

This is in turn the voiceless velar stop /k/ becomes [kj] before the front vowel /i/. Therefore, the rule for this palatalization is also formulated below:

Some adjectives are derived through prefixing {ga-} morpheme from a language name base. While there is no regular tone pattern in the base, the derived form has LLL(H) tone pattern as in (6).

Table 6: Example 6

| Base | Prefix + Base | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /bòole/ | /ga-+bòole+-aki / | [gàbòolakji] | Bole like |

b. | /bòore/ | /ga-+bòore+-aki / | [gàbòorakji] | Fulfude like |

c. | /nasara/ | /ga-+nasara+-aki / | [gànàsàrakji] | English like |

d. | /màpNni/ | /gà-+màpNni+aki/ | [gàmàpNnakji] | Hausa like |

As {ga-} is attached to the primary base in (6a-c), in (6d) it is added to a derived noun of the agent [mapNni] which is composed of {ma-} prefix and a noun base [apNno] ‘a Hausa man’. Additionally, it is observed that there is the deletion of the final vowel of the base before {-aki} suffixed is attached. Unlike in (5) where the base forms have the final vowel, here in (6) each of the bases has a different final vowel. Yet, the vowel is deleted and replaced with {-aki} which works simultaneously with the {ga-} in the derivation process of this category.

It is also observed that the schwa sound is deleted as the {ga-} prefix is attached to a verb base in the formation of participial adjective. Consider example (7) below:

Table 7: Example 7

| Base | Prefix + Base +Suffix | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /Ndbu/ | /ga-+Ndbu+-aki/ | [gàdbakji] | erected |

b. | /Nksu/ | /ga-+Nksu+-aki/ | [gàksakji] | boasted |

c. | /Nzgàtu/ | /ga-+Nzgàtu+-aki/ | [gàzgàtakji] | leaked |

Similarly, as can be seen in (8a&b) below, in deriving the participial adjective, the prefix triggers the weakening of the voiced velar /g/ sound of the verb base to become velar labial [w], at surface realization.

Table 8: Example 8

| Base | Prefix + Base +Suffix | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /gùɓu/ | /ga-+gùɓu+-aki/ | [gàwùɓakji] | wetted |

b. | /gùɗu/ | /ga-+gùɗu+-aki/ | [gàwuɗakji] | hasty |

The realization of /g/ as [w] in (8) above also justifies what is observed in examples (1) above under {ma-} prefixation. This process is attested by this paper that even at the syntactic level such weakening occurs, as far as the Southern Bade dialect is concerned. Consider the following examples in (9) below:

9.  a. ja gwùɗu -a → [ja wuɗa]

a. ja gwùɗu -a → [ja wuɗa]

(you 2m.sg verb-hurry future tense marker) → you are fast.

b. ja gwùɓu -a → [jawuɓa]

(you 2m.sg verb-wet future tense marker) you will wet (e.g., cloth)

Consequently, we can account for such a process in another way without diverging from the previous rule in (8) as follow:

The rule states that a voiced velar stop /g/preceding a low central vowel /a/ at the morpheme boundary becomes [w] before a high back rounded vowel /u/.

We observed that, unlike the {ga-} prefixation as in examples (5-8) above, here in example (9) there was neither deletion nor substitution of the final base form, but the vowel of the prefix is lengthened. For instance, the words maja ‘hungry’ and marwee ‘fear’ are verbal nouns, while makwasi throat and kazi ‘heart’ are nouns and kəma ‘front’ is an adverb. One interesting phenomenon worthy to note here is that, while in other West Chadic languages, Hausa in particular (cf. Sani, 2011), /w/ is palatalized before the front vowel to become [j], here, this is not the case in Bade. The /w/ in the marwee becomes [j] before the high back vowel /u/ to form the verb major ‘to fear’. This process is also observed especially in the case of the verb ‘to farm’ Nryu becoming the verbal noun Nrwen ‘farming’.

Back to long [a] in {ga-}prefixation, it is observed also that, some base forms that begin in /a/ sound form CVV syllable structure as in the following examples:

Table 10: Example 10

| Base | Prefix + Base | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /ama/ | /gà-+ama/ | [gàama] | female |

b. | /àmani/ | /gà-+àmani/ | [gàamani] | a year |

To conform with permissible syllable structure, not only in Southern Bade, but Bade language in general, the [a] onset of the base in /amani/, /ama, and /apǝno/, and with that of the {ga-} must surface as long vowel [aa], [gàamani], [gàama], and [gaapǝno] respectively. It can be deduced that the low vowel /a/ of {ga-} is combined with that of the base form to become long.

According to Dagona (2004:70), {saa-} is a “ prefix forming names for females who are named after a person with the name to which the prefix is added”. The base that is used in deriving female names could be either name of a male person or animal as can be seen in the following examples in (11):

Table 11: Example 11

| Base | Prefix + Base | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /mùuza/ | /saa-+mùuza/ | [sâmmuuzà] | femal name |

b. | /kàvayo/ | /saa-+kàvayo/ | [saakàva] | Female name |

c. | /kaakwu/ | /saa-+kaaku/ | [saakwù] | Female name |

d. | /kumbo/ | /saa- + kumbo/ | [saakumbo] | Femle name |

e. | /ʤa/ | /saa-+ʤa/ | [saaʤà] | Female name |

From the examples above, it can be seen that, in (11a), the vowel sound of {saa-} prefix is shortened while the first consonant of the base is geminated in the realization of the Musa’s namesake, that is [sâmmuuzà]. In the case of (11b), there was no gemination but rather a deletion of the final syllable of the base to become [saakava]. However, some speakers were heard saying [saavàjo] instead, meaning they deleted the first syllable of the base, just as the way [saaku] is formed in (11c). In the formation of [saaʤà], we noticed the changing of the tone of the base [ʤà] from a high tone to a low tone as the prefix is attached.

Another category of names that are derived through {saa-} prefixation is circumstantial names. The base forms here could be place names or verbal nouns. Consider the following examples in (12) below:

Table 12: Examples 12

| Base | Prefix + Base | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /duwa/ | /saa-+duwa/ | [sâgduwà] | female name |

b. | /taavi/ | /saa- taavi/ | [sâktaavì] | female name |

c. | /NgzNga/ | /saa-+NgzNga/ | [sâgzǝgà] | female name |

d. | /Nskùna/ | /saa-+Nskùnu/ | [sâskwunà] | female name |

|

|

|

|

|

From the examples in (12), we observed a shortening of /a/ in all of the derivatives and a deletion of /ə/ in (12c&d) that are all triggered by morphological constraint to conform with the permissible syllable structure of CVC of Bade language. In (12a&b) also, we noticed the presence of {-g-} and {-k-} genitival linkers that join the {saa-} prefix, which has the meaning of ‘time of’, with the base duwa ‘a river’ and taavi ‘war’ respective. The voiced velar /g/ is inserted when the base initial consonant is voiced, but if it is a voiceless initial consonant, a voiceless velar /k/ appears. (cf. Dagona, 2004:40). The shortening is caused by the coming of this link element in between the morphemes. Additionally, in (12c&d), it is observed that the bases begin in /ə/, as such the attachment of the {saa-} prefix causes its deletion leaving the first consonant of the bases to become code of the first syllable of the derived forms as sâgzǝgà and sâskunà respectively. The base əskuna ‘adding’ in (12d) is derived from the verb əskunu ‘to add’. Consider the following illustrations for more clarification:

From the examples in (12), we observed a shortening of /a/ in all of the derivatives and a deletion of /ə/ in (12c&d) that are all triggered by morphological constraint to conform with the permissible syllable structure of CVC of Bade language. In (12a&b) also, we noticed the presence of {-g-} and {-k-} genitival linkers that join the {saa-} prefix, which has the meaning of ‘time of’, with the base duwa ‘a river’ and taavi ‘war’ respective. The voiced velar /g/ is inserted when the base initial consonant is voiced, but if it is a voiceless initial consonant, a voiceless velar /k/ appears. (cf. Dagona, 2004:40). The shortening is caused by the coming of this link element in between the morphemes. Additionally, in (12c&d), it is observed that the bases begin in /ə/, as such the attachment of the {saa-} prefix causes its deletion leaving the first consonant of the bases to become code of the first syllable of the derived forms as sâgzǝgà and sâskunà respectively. The base əskuna ‘adding’ in (12d) is derived from the verb əskunu ‘to add’. Consider the following illustrations for more clarification:

Table 13: Example 13

a. | /duwa/ | UR |

| /saaduwa/ | {saa-} prefixation |

| /saa-g-duwa/ | insertion of link element |

| /sakduwa/ | shortening of /a/ |

| [sâgduwà] | SR |

b | /NgzNga/ | UR |

| /saaəgzəza/ | {saa-} prefixation |

| /saagzəga/ | deletion of schwa /ə/ |

| /sagzəga/ | SR |

c. | /Nskùna / | UR |

| /saaəskuna/ | {saa-} prefixation |

| /saaskuna/ | deletion of schwa /ə/ |

| /saskuna/ | shortening of /a/ |

| [sâskwuna] | SR |

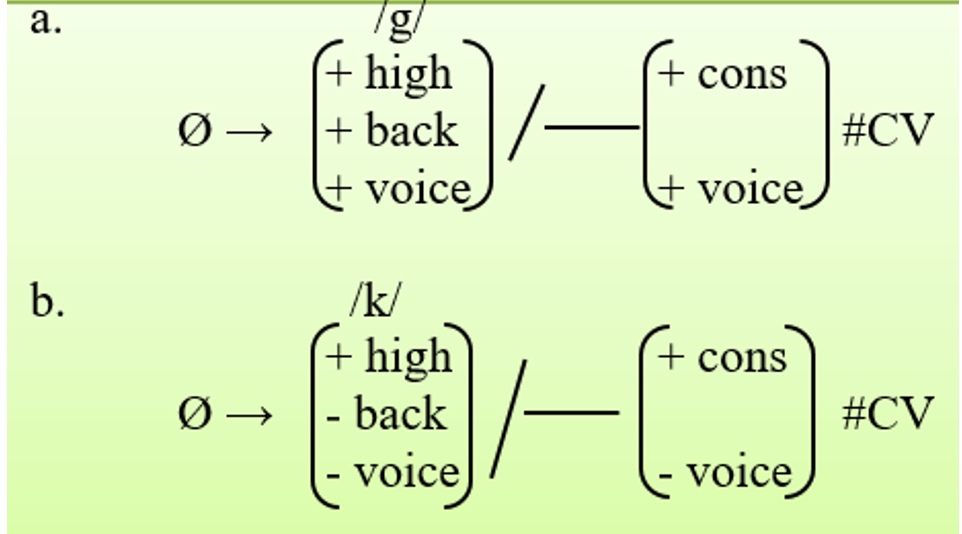

To capture this morphological insertion of {-g-} or {-k-} linker and shortening of /a/ in {saa-} prefixation, the following rules are formulated:

Rule (7): Insertion of {-g-}/{-k-} genitival linker

The rules in (7a) state that {-g-} link element is inserted in between {saa-} prefix and a word that begins in a voiced consonant other than a voiced velar sound; and rule (7b) states that {-k-} link element is inserted in between {saa-} prefix and word that begins in voiceless consonant other than voiceless velar sound.

While to account for the shortening of /a/ of the {saa-} prefix, the following rule is posited:

This rule (8) says that a long low vowel is shortened when appears in the sequence of two consonants at the morpheme boundary.

4. 4 {tN-} Prefix

The {tN-} prefix is 3rd person subject in 2nd subjunctive that when adds to a verb stem forms a personal name. It is a variant of {dN-} available in the western dialect of Bade. Three names are found to be formed by this process as indicated in (26).

Table 14: Example 14

| Base | Prefix + Base | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /làmu/ | /tN-+làmu/ | [tàlàma] | male personal name |

b. | /ùsu/ | /tN-+ùsu/ | [tàusi] | male personal name |

c. | /mànu/ | /tN-+mànu/ | [tàmàne] | male personal name |

d. | /vNru/ | / tN-+ vNru/ | [tàvàre] | male personal name |

Careful observation reveals that in (14a), the final vowel of the base form is substituted with /a/ plural formative suffix, literary meaning ‘let them say’. The final base vowel /u/ in (14b) is replaced with 2nd person singular morpheme /i/, literary means ‘let him assist’; and in (14c&d) it is substituted with ventive marker /e/ indicating the time of stay and coming out ‘hitherto’ respectively. While tàlàma is a name given to a child that is born outside wedlock, tàusi is a name given to a child whose parent has taken a long time without bearing. And, tamane, is given to an overstayed child in the womb, who is born after a year of pregnancy, while tàvàre is a name given to children during their delivery, legs started coming out.

It is observed that /ǝ/ is realized as [a] in the process of formations of derivatives in (14). We postulate the following rule (9) to account for the morphophonological sound change that occurred.

The rule states that a schwa /ǝ/ is realized as low [a] in the environment before the sound of the initial syllable of the base in the process of personal name formation.

4.5 {dǝ-} Prefix

Unlike the {tǝ-} prefix that is used in deriving personal names, the {dǝ-} prefix can be added to a transitive verb stem to indicate a stative adverb. Also, the schwa /ǝ/ sound remains unchanged at the surface realization. The tonal pattern of the derived form is L(H)L. The following data in (15) indicate that:

Table 15: Example 15

| Base | Prefix + Base | Derivative | Gloss |

a. | /bo/ | /dǝ-+bo/ | [dNbà] | gotten |

b. | /so/ | /dǝ-+so/ | [dNsà] | drank |

c. | /to/ | /dǝ-to/ | [dNtà] | ate |

d. | /gàfo/ | /dǝ-+gàfo/ | [dNgafà] | caught |

e. | /bNnu/ | /dǝ-+bNnu/ | [dNbǝnà] | cooked |

d. | /mbNlu/ | /dǝ-+mbNlu/ | [dNmbǝlà] | disconnected |

One observes that in the process of forming the stative adverb, the final vowel of the verb stem is replaced with the [a] suffix. Additionally, there are some stative adverbs that are formed through {dN-} prefixation. The derivatives function as in continuous present tense, normally attributed to animate, such as [dǝvadi] and [dǝlagji] as in aʧi dNvadi ‘he’s sleeping’ and aʧi dǝlagji ‘he’s standing’ respectively. Therefore, in forming stative adverbs, there is always a {də-} prefix added to a verb stem, followed by a {-i} suffix person marker that replaces the final vowel of the verb stem. Consequently, the following rule represents the process of substitution of the final base vowel triggered by the prefix:

One observes that in the process of forming the stative adverb, the final vowel of the verb stem is replaced with the [a] suffix. Additionally, there are some stative adverbs that are formed through {dN-} prefixation. The derivatives function as in continuous present tense, normally attributed to animate, such as [dǝvadi] and [dǝlagji] as in aʧi dNvadi ‘he’s sleeping’ and aʧi dǝlagji ‘he’s standing’ respectively. Therefore, in forming stative adverbs, there is always a {də-} prefix added to a verb stem, followed by a {-i} suffix person marker that replaces the final vowel of the verb stem. Consequently, the following rule represents the process of substitution of the final base vowel triggered by the prefix:

This rule states that the base final sound /u/ or /o/ is substituted with low [i] in deriving a stative adverb.

5. Conclusion

In this work on Southern Bade Prefixation, it has been seen the derivational processes involving prefixes that have semantic significance in the realization of the derivatives. Five derivational prefixes are found in the nominal system of the dialect. As seen in the paper, in some instances, the prefixation triggers alternation of the final base vowels they are added to by deletion or substitution. The morphophonological alternations that occurred in the prefixation processes include weakening of voiced velar /g/ to becoming labial velar [w]; schwa [ə] deletion re-syllabification; insertion of link element; deletion, labialization velars [kw, gw] before back vowels /o u/ and palatalized [kj, gj] before front vowels /e, i/ respectively. The {ma-} prefix is used in deriving agential noun, personal and instrument names, {ga(a)-} in forming participial adjectives and adverbs, {saa-} in deriving female namesake and circumstantial names; {tə-} and {də-} are used in deriving personal name and adjective respectively from a verb base.

Reference

1. Abubakar, A. (2000). Introductory Hausa Morphology. Maiduguri: Faculty of Arts, University of Maiduguri, Occasional Publication.

2. Ago, A. S. (2015). Kwatanta Gamayyar Tasrifi da Tsarin Sautin Hausa Da Na Badanci. (Unpublished master’s dissertation). Bayero University, Kano.

3. Al-Hassan, B. Y. S. (1998). Reduplication in the Chadic Languages: a Study of Form and\ Function. (European University Studies; Series 21: Linguistics 191). Frankfurt/Main: Peter Lang Publishing.

4. Aronoff, M. and Fudeman, K. (2005). What is Morphology? USA: Blackwell Publishing.

5. Crystal, D. (2008). A Dictionary of Linguistics and Phonetics. 6th Edn., New York. Blackwell.

6. Dagona, B. W. (2004). Bade – English – Hausa Dictionary (Western Dialect). Potiskum: Ajami.

7. Fagge, U. U. (2004). The Status of Bound Morpheme ma- in Hausa. In Algaita Journal of Current Research in Hausa Studies No. 3, Vol. 1. Kano: Benchmark Publishers Limited. pp.66-77.

8. Haspelmath, M. and Sims, A. D. (2010). Understanding Morphology. London: Hodder Education, an Hachette UK Company

9. Jensen, J. T. (1995) Morphology: Word structure in Generative Grammar. USA: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

10. Mamman, M. (2012). The Hausa Bound Morphemes ‘ma-’, ‘ba-’ and others: a Critical Study of their Forms and Functions. In Essays on Hausa Grammar and Linguistics (ed). Zaria: ABU Press. pp. 29-40

11. Matthews, P. H. (2006) Morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

12. Newman, P (1977). Chadic Classification and Reconstruction. Afro-asiatic Linguistic, 5(1): 1- 42.

13. Newman, P. (2000). The Hausa Language an Encyclopedia Reference Grammar. New Haven: Yale University Press.

14. Nuhu, Y. I. (2017). Circumfixation as a Morphological Process in Hausa. In Yusuf, M. A., Salim, B. A., and Bello, A. (eds) Endangered Languages in Nigeria: Policy, Structure and Documentation. Vol. II. Kano: Bayero University Press. pp. 651-660.

15. Olga, A. (1971). Phonology, Morphophonology and Morphology. Paris: De Gruyter Mounton.

16. Salisu, T. (2015). A Phonological Description of Bade Central Dialect. (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Maiduguri, Borno, Nigeria.

17. Sani, M.A.Z. (2011). Gamayyar Tasrifi da Tsarin Sautin Hausa. Zaria: A.B.U Press Plc.

18. Schuh, R. G. (1977a). Bade/Ngizim Determiner System. Monography of the NearEast Afroasiatic Linguistics. Vol. 4 Issues 3. Malibu: Undena Publication.

19. Schuh, R. G. (1978). Bade/Ngizim Vowels and Syllable Structure. Studies in African Linguistics, Vol. 9, Number 3. p 247-283.

20. Schuh, R. G. (1981). Using Dialect Geography to Determine Pre-history: A Chadic Case Study. Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, 3: 201-250.

21. Schuh, R. G. (2007). The Nominal and Verbal Morphology of Western Bade. Morphologies of Asia and Africa Vol. I, pp 587- 639

22. Sunoma, A. (2010) A History of Bade in the Pre-Colonial Period. Ibadan: Boga Press

23. Tarbutu, M. M. (2004). Bade – English – Hausa Dictionary (Gashua Dialect). Potiskum: Ajami.

24. Tela, M. M. (2014). Kwatancin Ginin Kalmar Hausa da Na Badanci. (Unpublished master’s dissertation). Ahmadu Bello University, Zaria, Nigeria.

25. Ziegelmeyer, G (2011). On the Verbal System of Gashua Bade. In: Afrikanistik online, http://www.afrikanistik-online.de/archiv/3756

0 Comments

ENGLISH: You are warmly invited to share your comments or ask questions regarding this post or related topics of interest. Your feedback serves as evidence of your appreciation for our hard work and ongoing efforts to sustain this extensive and informative blog. We value your input and engagement.

HAUSA: Kuna iya rubuto mana tsokaci ko tambayoyi a ƙasa. Tsokacinku game da abubuwan da muke ɗorawa shi zai tabbatar mana cewa mutane suna amfana da wannan ƙoƙari da muke yi na tattaro muku ɗimbin ilimummuka a wannan kafar intanet.