Cite this article as: Bulaun, D. (2023). Cognitive Semantic Analysis of the Verb, ‘Tuur’ in TIV. Tasambo Journal of Language, Literature, and Culture, (2)2, 54-66. www.doi.org/10.36349/tjllc.2023.v02i02.007.

Doofan Bulaun (PhD)

Department of English and Other Languages, University of Mkar, Mkar, Benue State, Nigeria

Doofanbulaun71@gmail.com

07059078087, 07032438887

Abstract

This study presents a cognitive semantic analysis of the verb tuur ‘push’ in the Tiv language. As a contribution to the ongoing research on indigenous language verbs in cognitive linguistics generally and cognitive semantics in particular, the study uses the cognitive semantics approach to examine the Tiv language verb tuur, ‘push’ beyond the structure of the verb and `into the psychological and abstract semantics of the verb. The central objective of this study is to initiate a cognitive semantic study of Tiv verbs. The theoretical framework adopted for the analysis of the meanings of the verb is cognitive semantics. In an attempt to study the semantics of the verb ‘tuur’ we examine the role three image schemas (namely containment, path and force schemas) play in conceptual interaction with tuur, especially about metaphor (Lehrer and Feder, 1992). The findings show that the experience we have as we go through the maturing stage of life, as interaction takes place in society motivates basic conceptual structure which makes understanding and language possible. The study reveals that the verb falls into three image schemas follows the CONTAINMENT, the PATH and the FORCE (Jackendoff, 1990). The study also reveals that ‘tuur’ is not semantically empty. Our analysis also discloses that the image schemas of ‘tuur’ are conceptual constructs which can be metaphorically extended from physical to psychological and concrete to abstract domains. Further research requiring a broader database is recommended herewith to ascertain other possible schemas and metaphorical meaning extensions of the verb.

Keywords: TIV, Verbs, Tuur

1.0 Introduction

Evans and Green’s (2006:50), cognitive semantics, “investigates the connections between human experiences, conceptual systems and semantic structures expressed through language”. According to Evans, Bergen and Zinken (2007:6-9), four guiding principles that collectively characterize a cognitive approach to semantics are as follows:

i. Conceptual structure is embodied

ii. Semantic structure is a conceptual structure

iii. Meaning representation is encyclopedic

iv. Meaning construction is the conceptualization

Embodied cognition maintains that due to the nature of our neuroanatomical design, we have a species-specific view of the world. This reflects in our understanding of reality due to the nature of our embodiment. Meaning that the concepts we have access to and the nature of ‘reality’ as we think and talk are a function of our embodiment. We can only talk about what we can perceive and conceive, and the things that we can perceive and conceive come from embodied experience.

The second guiding principle may be seen to mean that language refers to concepts in the mind of the speaker rather than, directly, to entities in an objectively real external world. The meaning conventionally associated with words and other linguistic units (semantic structure) can be equated with concepts (conceptual structure). This is not to claim that semantic structure and conceptual structure are identical. Instead, cognitive semanticists claim that the meanings associated with linguistic units such as words, for example, form only a subset of possible concepts. After all, we have many more thoughts, ideas and feelings that we can conventionally encode in language.

The third guiding principle holds that semantic structure is encyclopedic in nature. This means that lexical concepts do not represent the full meaning of words. They rather serve as ‘points of access to repositories of knowledge relating to a particular concept or concept domain. However, cognitive semanticists argue that the conventional meaning associated with a particular linguistic unit is simply a ‘prompt’ for the process of ‘meaning construction,’ that is the ‘selection’ of an appropriate interpretation against the context of the utterance.

The fourth guiding principle is that language itself does not encode meaning instead, as we have seen in the third principle above, words (and other linguistic units) are only ‘prompts’ for the construction of meaning. Implying that meaning is constructed at the conceptual level. This is a process whereby linguistic units serve as prompts for an array of conceptual operations with the help of background knowledge. These guiding principles are adopted as a guide for this study.

As a contribution to the ongoing research on indigenous language verbs and cognitive linguistics in general and cognitive semantics in particular, the study uses the cognitive semantics approach to examine the Tiv language verb tuur, ‘push’ beyond the structure of the verb and `into the psychological and abstract semantics of the verb. In addition, the study looks at the verb root as reflecting some specific patterns of conceptualization. Finally, this study employs metaphor and image-schema as types of cognitive structuring which are examined to see how these concepts are used to extend the meaning of conceptual interactions or structures in Tiv.

In terms of methodology the data were collected by informal interviews with native speakers of the language and the researcher also relied on her intuitive knowledge as a native speaker.

1.1Theoretical Studies

The central concern of some linguists such as Fauconnier (1995, 2002), Fillmore (1975, 1976), Lakoff (1987, 1992), Langacker (1975, 1991) and Talmy (2000a, 2000b) as well as Geeraerts and Cuyckens (2007) for two to three decades now has come to be known generally as ‘cognitive linguistics’. Its concern is the linguistic representation of the conceptual structure. Talmy (2011) says that this field can be characterised by contrasting its ‘conceptual’ approach with two other approaches, the ‘formal’ and the ‘psychological’.

The formal approach according to him focuses on the overt structural patterns exhibited by linguistic form, largely abstracted away from any associated meaning. This approach thus includes the study of syntactic and morphemic structure. The tradition of generative grammar has centred on the formal approach (Cruse, 1986). But its relation to the other two approaches (the psychological and conceptual) has remained limited. It has all along referred to the importance of relating its grammatical component to a semantic component, and there has indeed been much good work on an aspect of meaning but has generally not addressed the overall conceptual organisation of language.

The psychological approach regards language from the perspective of general cognitive systems such as perception, memory, attention and reasoning. Centred on this approach, the field of psychology has also addressed the other two approaches. Its conceptual concerns have in particular included semantic memory, the associativity of concepts, the structure of categories, inference generation, and contextual knowledge. But it has insufficiently considered systematic conceptual structuring of the globally integrated system of schematic structures with which language organizes conceptual content.

Cann (1993) recognized two main dimensions of meaning: logical (or referential) and emotive. Ndimele (1997) categorized the component shades of meaning into three: conceptual, associative and thematic meanings of language. Lyons (1977) theorized about ‘descriptive’ and ‘expressive’ meanings. There is also the distinction between denotative and connotative levels of meaning identified by J. S. Mill (1843). These attempts and terminologies overlap in the sense that they recognize the capability of words and expressions in language to mean more than their everyday meaning. However, our primary concern in this study is cognitive semantics.

Several studies have been carried out using the theories of cognitive semantics. Zlater (1999) for instance, uses computer modelling to give an account of how linguistic expressions are grounded in experience. He presents an approach which he calls “situated embodied semantics”, in which meaning emerges from pairing linguistic expressions with situations.

Velasco (2001), cited in Ogbonna (2013), examines the role of three image schemas (CONTAINER, PART/ WHOLE and EXCESS) play in conceptual interaction, particularly about metonymy. This study shows that image schemas have two basic functions. Firstly, they structure the relationship that exists between the source and the target domain of metonymic mapping and secondly, they provide the axiological value of an expression. He concludes that the appearance of image-schemas in conceptual interaction is more ubiquitous than it may seem at first sight and that conceptual interaction frequently invokes the activation of the three types of cognitive model (metaphor, metonymy and image schemas) he examined.

1.2 Empirical Studies

In this section, we review works carried out by scholars in this field.

Viberg (1999) shows interest in the semantic structure of verbs in Swedish from a cross-linguistic perspective. With the image schema, he investigates the semantic field of ‘physical contact verbs’, for example, sla (strike/hit/beat). According to him, verbal semantic fields are usually organized around one or sometimes several “nuclear verbs”. The verb sla is such a verb for physical contact verbs. He claims that other verbs of the field can be seen as elaborations or specifications of some aspects of sla. In this way, the analysis of the nuclear verb sla can be used to impose a structure on the whole field of physical contact verbs.

Sjostrom (1999), in the same vein, describes and discusses polysemy of lexical expressions (verbs, nouns and adjectives) connected with vision in Swedish. He uses his analysis to explore the relationship between vision and cognition. For example, he claims that ‘light’ metaphorically represents ‘knowledge’ and that accordingly; perception of light represents understanding while non-perception of light represents lack of understanding.

No studies have been done in the area of cognitive semantics of the Tiv verb by any scholar known to the researcher. Udu (2009) opines that Tiv verbs are a group of words known for expressing action, they help to know if an action is ongoing (progressive), was completed (past), is yet to happen (future), or the state of being. As illustrated below;

1. M yé abun (I eat groundnuts). This shows that eating groundnuts is what I do always (as a habit).

2. M yè abun. (I eat groundnuts). This means that some time ago, I ate groundnuts, but now I am not eating them.

3. M ngu yan abun. (I am eating groundnuts). This means that at this very moment that I am talking to you what I am doing is eating groundnuts.

4. Me ya abun. (I will eat groundnuts). This means that if I am offered groundnut I will eat. It also means that at the designated time, I will eat groundnuts, but I am yet to eat them at the time of talking to you.

Structurally,1 and 2 above are the same. The verb form is also the same. But a tone shift in the pronunciation of the verb ‘ye’ will bring about the distinction between the two. In 1, ‘yé’ is simple present, in 2, ‘yè’ is simple past. Udu further explains that Tiv’s main verbs are one–word action words that express what the subject of the verb does while auxiliary verbs help the main verb to express action. Ayem (2010:87) also opines that “the Tiv verb denotes an action as well as a state of being”. He further identifies the features of Tiv verbs in his efforts to study the Tiv language verb generally. The efforts made to study Tiv verbs by both scholars mentioned above, have no direct bearing on the present study which is a cognitive semantic study of the verb ‘tuur’. The researcher, therefore, studies works done in the area of cognitive semantics in other indigenous languages that relate to the present study, to determine their applicability.

A few studies on the cognitive semantic analysis of Igbo verbs have been done by Igbo scholars. They are Uchechukwu (2011), Edeoga (2012) and Ogbonna (2013). Uchechukwu (2011) states that his effort to examine the semantics of the Igbo verb tu ‘throw’ with the cognitive linguistic tool of image schema analysis is connected with the general conclusion within the syntactic approach that the verb root is empty. This conclusion according to him is best reflected in Nwachukwu’s (1987:83) statement that “the greater the number of verbal complexes formed with a verb root, the more practically meaningless the verb root becomes”. However, based on an image schema analysis, he argues that the Igbo verb is not empty; neither does it become practically meaningless as a result of an increase in the number of verbal complexes formed with it. He identifies the verb to as an instance of the SOURCE-PATH-GOAL schema.

Edeoga (2012) examines the semantics of the Igbo verb sè ‘draw’. She examines the role of CONTAINMENT, SOURCE-PATH-GOAL and COMPULSION (FORCE) schemas play in conceptual interaction with the verb se, especiallaboutto metaphor. The paper reveals that the common human experience of maturing and interaction in society motivates basic conceptual structures that make understanding language possible. The paper also reveals that the verb se is not empty and that metaphor and image schemas can be used to extend meaning by transforming one conceptualization into another that is roughly equivalent in terms of content but differs in how this content is construed.

Ogbonna (2013), in the same vein, examines the semantics of the Igbo verb ‘kwa’. She examines the role the image- schemas; PATH schema as well as COUNTERFORCE and ENABLEMENT of FORCE schemas play in conceptual interaction with kwa, particularly about metaphor. The paper reveals that the ‘kwa’ verb fits into two types of force image – schemas; counterforce and enablement. The paper also reveals that the kwa verb image – schemas are experientially based conceptual constructs which can be metaphorically extended across a range of domains which serve as the building blocks of metaphor. The paper concludes that the verb root kwa is not empty. From the theoretical and empirical reviews on cognitive semantic studies, it is clear that none of the studies referred to above studied Tiv even in the remotest sense. Again, no work known to the researcher has treated the Tiv language from the perspective adopted in this paper. The works neither examine the Tiv verb ‘tuur’ nor determine the applicability of different image schemas to the verb. It is for these obvious reasons that this study attempts to investigate the verb to find out if it is semantically empty to determine the role of image-schemas: PATH schema, COUNTERFORCE, ENABLEMENT of FORCE, BLOCKAGE and REMOVAL of RESTRAINT FORCE schemas as well as CONTAINMENT schemas play in conceptual interaction with tuur, particularly about metaphor.

1.3 Theoretical framework

Cognitive linguistics was developed from the works of some linguists such as Fillmore (1975), Rosch (1975), Langacker (1987, 1991), Lakoff (1987), Fauconnier (1985), Fauconnier and Turner (2000), Talmy (2000, 2011), Evans, Bergen and Zinken (2007), Croft and Cruse (2004) as well as through edited collections like Geeraerts and Cuyckens (2007). According to Croft and Cruse (2004:1),” cognitive linguistics is taken to refer to the approach to the study of language that began to emerge in the 1970s and has been increasingly active since the 1980s… with three major tenents guiding the cognitive linguistic approach to language: that language is not an autonomous cognitive faculty, grammar is the conceptualization and knowledge of language emerges from language use.” Language structure is studied within the cognitive linguistic framework “as reflections of general conceptual organization, categorization principles, process mechanism, and experiential and environmental influences” (Geeraerts and Cuyckens, 2007:4). In this definition, language is viewed as an instrument for organizing, categorizing, processing, and conveying information. Cognitive linguistics has generally concerned itself with the linguistic representation of the conceptual structure. Talmy (2011:1) is of the view that this field can be characterised by contrasting its “conceptual” approach with two other approaches, “the formal” and “the psychological.” The formal approach focuses on the overt structural patterns exhibited by linguistic forms, while the psychological approach regards language from the perspective of general cognitive systems such as perception, memory, attention and reasoning.

In contrast, the conceptual approach of cognitive linguistics is concerned with the patterns in which and processes by which conceptual context is organized in linguistic structuring of such basic conceptual categories as space and time, scenes and events, entities and processes, motion and location and force and causation. Adding the basic ideational and affective categories attributed to cognitive agents such as attention and perspective, violation and intention, and expectation and affect. It addresses the semantic structure of morphological and lexical forms, as well as of syntactic patterns. And it addresses the inter-relationships of conceptual structures such as those in metaphoric mapping, within a semantic frame, between text and context, and those in the grouping of contextual categories into large structuring systems. The main aim of cognitive linguistics is to ascertain the globally integrated system of conceptual structuring in language.

Cognitive semantics, which is the focus of this study, is a branch of cognitive linguistics that deals with meaning and conceptualization. It offers a new approach to the conceptual system of figurative language and sense relations in the lexicon. It assumes that language is compositional and regards motivation as a key issue in language use (Langacker 1991:295). It stresses the relationship between performance and competence. Chomsky (1976) stresses the distinction between the ability that we demonstrate when using a language and the language itself. He opines that language itself is not a capacity (or ability), but a cognitive structure and that we can even possess language as a cognitive structure without having the ability to use it. Meaning that knowledge and understanding are not at the same level as capability. Clausner and Croft (1999:2) postulate that the most basic theoretical construct of cognitive semantics is the concept, that is, a basic unit of mental representation. This is because the meaning of a linguistic expression is equated with the concept it expresses. Thus, the concept cannot be understood independently of the domain in which it is embedded.

Saeed (2003: 344) states that “in the literature of cognitive semantics, meaning is based on conventionalized conceptual structure”. As a result, semantic structure along with other cognitive domains reflects the mental categories which people have formed from their experience of growing up and acting in the world. Hence, the real focus of investigation in cognitive semantics should be conceptual framework and how language reflects them.

Cognitive linguistics, therefore, sees image schemas as pre-conceptual topological abstractions which serve to organize much of our experience and understanding of the world (Johnson, 1987; Lakoff, 1987, 1989; Turner 1987, Gibs and Colston, 1995). The theoretical construct of the image schema was developed in particular by Johnson (1987) when he proposed that the embodied experience manifests itself at the cognitive level in terms of images schema imagee Then, image schema theory has played a major role in several areas of study such as literary criticism (Turner 1987); psychology (Mandler, 1992); psycholinguistics (Gibbs and colston, 1995); cognitive grammar (Lakoff 1987); Mathematics (Lakoff and Nunez, 2000), cognitive semantics (Uchechukwu 2011, Edeoga 2011 and Ogbonna 2013).

Image schemas are pervasive skeletal patterns of a pre-conceptual nature which arise from everyday bodily and social experiences and which enable us to mentally structure perceptions and events (Johnson 1987; Lakoff, 1987, 1989). In other words, according to Saeed (2003: 353), the basic idea of image schema “is that because of our physical experience of being and acting in the world; perceiving the environment, moving our bodies, exerting and experiencing force, etc, we form a basic conceptual structure which we then use to organize thought across a range of more abstract domains”. With cognitive linguistics, these recurrent non-propositional models are taken to unify the different sensory and motor experiences in which they manifest themselves in a direct way and, most significantly they may be metaphorically projected from the realm of the physical to other more abstract domains.

For our analysis of conceptualizations of the verb ‘tuur’ (push) a combination of image schema will capture the complex conceptualization of this verb. For instance, pushing an object from point ‘A’ to point ‘B’ fits the image schema of PATH (SOURCE-PATH-GOAL). In addition to the PATH schema, the verb tuur ‘push’ itself requires some forces, hence, COUNTERFORCE, ENABLEMENT, BLOCKAGE and REMOVAL of RESTRAINT and CONTAINMENT schemas will also be adopted for our analysis. The process of navigating from the physical to psychological and concrete to abstract domains is referred to as analogical mapping (Saeed 2003).

1.4 Data Presentation and Analysis

Image-schema of the verb ‘tuur’

The image-schema of the verb ‘tuur’ (push) is discussed under three broad image-schemas: PATH, FORCE and CONTAINMENT. However, the instance of PATH to be adopted is SORCE-PATH-GOAL schema, while aspects of FORCE to be applied are COUNTERFORCE, ENABLEMENT, BLOCKAGE and REMOVAL of RESTRAINT FORCE schemas and finally CONTAINMENT schema.

PATH Schema

Uchechukwu (2011:46) sees the PATH scheme as an “imaginative trajectory that is conceptualized as a line-like ‘trail’ left by an object as it moves and projects forward in the direction of motion”. It can include a moving vehicle, the speed of motion, obstacles to motion (blockage) as well as forces that move along a trajectory, la the trail or actual movement of any ‘push’ object. In all such instances, a SOURCE-PATH-GOAL schema can be conceptualized.

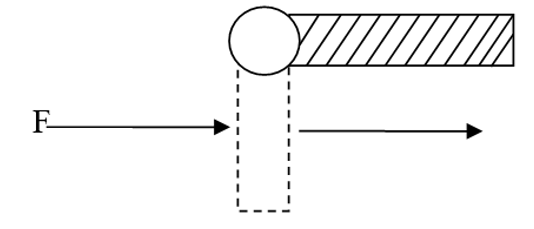

Saeed (2003:355), quoted in Ogbonna (2013:9) states that “PATH schema reflects our everyday experience of moving around the world and experiencing the movements of other entities”. He asserts that our journeys typically have a beginning and an end. Other movements may include projected paths like the flight of a stone thrown through the air. Based on such experiences, the PATH schema contains a starting point (marked A, in figure1), an endpoint (marked B), and the distance connecting them (marked by the arrow):

Figure 1:

According to Saeed (2003), this schema has the following associated implications:

i) Since A and B are connected by a series of contiguous locations, getting from A to B

implies passing through the intermediate points.

ii) Paths tend to be associated with directional movement along them, say from A to B.

iii) There is an association with time. Since a person traversing a path takes time to do so.

The following examples are some instances of PATH schema:

1. Aondona ngú – tuur Agugu.

Aondona is pushing a motorcycle

Aondona AUX - push the motorcycle

[Literal: Aondona is pushing a motorcycle]

‘Aondona is pushing a motorcycle’.

Where Aondona started pushing the motorcycle is the SOURCE. From that point, Aondona’s destination is the PATH, while Aondona’s destination which may be his home is the GOAL.

The conceptualization of tuur is connected with what Croft (1993:338) refers to as a profile or base relationship. The profile stands out against the base while the base is that aspect of knowledge which is necessarily presupposed in conceptualizing the profile. In example 1, Aondona’s destination which is the base here is presupposed.

2. Terfa ngú – tuur wheel baro ke kasua kuran ior ikav.

Terfa is pushing wheelbarrows in the market packing people’s loads.

Terfa AUX – push barrow PREP. in market packing people load.

[Literal: Terfa is pushing barrow inside market packing people’s load]

‘Terfa uses a barrow to carry the load for people in the market’.

In 2 above, the ‘market’ which was the location from where Terfa carries the load is the SOURCE. The distance Terfa covered from the SOURCE to the target domain is the PATH, and the presupposed target domain is the GOAL.

3. Mne ngú – tuur mngerem mátseen harn Mimi iyol.

Mne is pushing water hot pouring Mimi body

Mne AUX – push hot water and pour mimi body

[Literal: mne is pushing hot water pouring Mimi body]

‘Mne is pouring hot water on Mimi’.

In 3 above, the SOURCE of the hot water is Mne. The distance the hot water moved from Mne to Mimi is the PATH, while Mimi is the GOAL.

In example 1, the verb tuur can be translated to mean ‘push’ but that is not the case with 2 and 3 where tuur means ‘use’ and ‘pour’ respectively. This shows that different meanings can be associated with the verb based on the complement that selects the verb. We also observe that in addition to the concrete meanings of examples 2 and 3 as stated above; metaphorical extension of the concrete meaning of ‘tuur’ can also be experienced in Tiv, as in 4 below;

4. Ican ngi–tuur Adoo ngi yemem aná ki ku

Poverty is pushing Adoo is taking her to death

Poverty AXU-push Adoo taking her to death

[Literal: poverty is pushing Adoo and taking her to death)

‘Poverty is leading Adoo to death

Example 4 involves the conceptualization of the same movement of pushing but within the psychological domain since poverty does not possess hands to push.

FORCE schema

According to Johnson (1987), FORCE schema is an image schema that involves physical or metaphorical or causal interaction. The force schemas examined here are; BLOCKAGE, REMOVAL of RESTRAINT, COUNTATER FORCE and ENABLEMENT of FORCE schemas as follows;

Blockage Force schema

Figure 2: blockage

Source: Mark Johnson (1987. P154)

Figure 2 is the specific schema of blockage; here a force meets an obstruction and acts in different ways, by being diverted or continuing to move by moving the obstacle or by passing through it as illustrated above.

Removal of Restraint schema

Figure 3: Removal of Restraint

Source: Mark Johnson (1987.P154)

Figure 3 reveals the schema of Removal of Restraint, this is a situation where the removal by another cause of blockage allows an exertion of force to continue along a trajectory. These schema like others arise from our day-to-day experiences as we grew and interacted with the world.

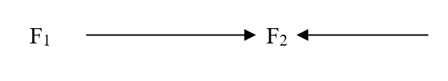

COUNTERFORCE Schema

Johnson (1987:46) defines the COUNTERFORCE schema as “two equally strong, nasty and determined force centres that collide face-face, with the result that neither can go anywhere”. In other words, it is a force. Here, there are two force vectors which move along a path and they collide face-face because both want to control the situation. This is represented schematically in Figure (4) below:

Figure 4: Counterforce Image schema

Source: Evans and Green (2006.P188)

Figure (4) shows where two force vectors F1 and F2 meet with equal force like when we bump into someone in the street.

Examples of FORCE schema of CONTERFORCE are as follows:

Example 5 is a physical manifestation of the COUNTERFORCE schema.

5. Iyongu ihyár ta ityoúgh tuur akough tavѐ.

Sheep two hit head push horns hard

Sheep two are AUX-push horn

[Literal: that two sheep hit head pushing horn]

‘That two sheep are locking horns’.

In 5 above, the two sheep are the two force vectors. The first sheep is the vector force F1 and the second sheep is the vector force F2. Both of them moved along a trajectory but meet each other or locked horns with equal forces. The sheep exchanged forces from equal and opposite directions; hence, a conceptual schema unites the characterization of the two actions. This is a concrete instantiation of the motion of ‘push’ from two opposing directions. Consider, the metaphorical extension of this concrete meaning in example 6, below:

6. Wuná man Ipav zua-tuur akoúgh tavѐ

Wuna and Ipav join and push horns hard

Wuna CONJ Ipav AUX-push horn hard

[Literal:Wuna and Ipav are pushing the horn hard]

‘Wuna and Ipav are competing seriously’.

Here, Wuna and Ipav are F1 and F2 respectively. ‘Wuna’ is the psychological vector F1 and Ipav is the psychological vector force F2. The centre of contact is the football field where the football competition is taking place. Here, the verb tuur is used in the real world of social activity, which involves the conceptualization of the same movement in example 5 but within the psychological domain since neither Wuna nor the Ipav possesses horns. Hence, example 6 is a metaphorical extension of the concrete meaning in example 5.

Enablement schema

ENABLEMENT schema is a force schema that “involves the physical or metaphorical power to perform some act, or a potential force and the absence of blockage or counterforce” (Johnson 1987:47). In other words, ENABLEMENT takes place when people become aware that they have some power to carry out some task, this image-schema derives from our sense of potential energy, or lack of it, in related actions because there exists no obstacle or counterforce to the performance of a specific task. We should note that while this image schema does not involve an actual force vector, it does involve a potential force vector. According to Johnson (1987), it is this property that makes the ENABLEMENT schema a distinct image schema. As illustrated below:

7. Ternengè vihi ishima je ta-tuur ityoúgh ke kon.

Ternege spoil heart till hit push head into tra ee

Ternengè spoil heart AUX-push head PREP tree

[Literal: Ternengè spoil heart hit push head at the tree)

‘ Ternenge hit and push his head against a tree out of anger’.

In 7 above, Ternenge is empowered (enabled) by anger to hit his head against the tree. If there had been a blockage (joy) or a counterforce Ternenge might be powerless to perform such an act against himself. Another example of ENABLEMENT is 11 below:

8. Terkimbi gbedyégh wégh sha gbandè-tuur amar a ember ishima.

Terkimbi beat hand on drum push dance with joy heart

Terkimbi beat drum AUX-push dance PREP happiness heart

[Literal: Terkimbi beat hand on drum pushing dance happiness heart]

‘Terkimbi is playing the drum and dancing with happiness’.

In 8 above, Terkimbi who has the energy to play music is doing so out of happiness. Hence, happiness motivates and enables him to play music. If there is an obstacle like anger, Terkimbi may not have the stimulus to play his music. In example 7, since there is no obstacle which blocks the movement towards the intended destination (intention), the entity (performer) achieves his intention.

Other instances of ENABLEMENT schema are where the meaning of the verbal complex conceptualization of tuur involves both concrete instantiations of the motion of ‘push’ as well as the metaphorical extensions of the concrete meaning. This is in line with Saeed’s (2003:352) assertion that metaphor, as one type of cognitive structuring, is seen to derive lexical change in a motivated way, and provides a key to understanding the creation of polysemy and the phenomenon of semantic shift. As illustrated in the examples below:

9. Orduè tough ashe abuun tuur Iorwa yam ke kpeh

Ordue carries eye-opening push Iorwa to go conner.

Ordue carry eye-opening push (PAST) Iorwa PREP conner

[Literal: Ordue pushed Iorwa with open eye go conner]

‘Ordue wisely pushed Iorwa to the conner’

10. Iveren tough ashe abuun tuur wuese nyor amin ke kwaghbo.

Iveren carries an eye-opening push on Wuese to enter inside in trouble

Iveren carry eye-opening pushed (PAST) Wuese PREP in something bad

[Literal: Iveren carry eye-opening pushed Wuese inside bad thing]

‘Iveren lured Wuese into evil’.

In 9 above, Ordue applied wisdom, which enabled him to physically push Iorwa to the house, however, example 10 involves the conceptualization of the same movement of pushing in but within the psychological domain, hence example 10 is the metaphorical extension of the concrete meaning of the push in example 9.

11. Wuese a shima I mhόόn tuur ngo na zá ke hemen

Wuese with a heart of mercy pushes Mother her go in forward.

Wuese with heart pity pusheMotherer her go forward

[Literal: Wuese pushes her mother forward]

‘Wuese pushed her mother forward out of pity’

12. Iwanger a shima I mhόόn tuur ngo na za hemen

Iwanger with a heart of mercy pushes Mother her go forward

Iwanger with heart pity pushes Mother her go forward

[Literal: Iwanger with heart pity pushes her mother forward]

‘Iwanger made her mother progressive out of pity’

In 11 above, pity enabled Wuese to physically push her mother forward. While 12 involves the conceptualization of the same movement of pushing forward but within the psychological domain, hence, example 12 is the metaphorical extension of the concrete meaning of the push in example 11.

13. Mne tough ibume tuur ayoosu sar akaa hen ya- ná.

Mne carry foolishness push noise destroy things here house her.

Mne carry foolishness push-trouble scatter(PAST) things house

[Literal: mne carry foolishness push-trouble scatter her house]

‘Mne scattered her house out of foolishness’

14. Mne tough abuse tuur ayoosu sar ya- ná.

Mne carry foolishness push noise destroys house here

Mne carry foolishness push-trouble scatter (PAST) house here

[Literal: Mne carry foolishness push-trouble scatter her house]

‘Mne disorganized her house out of foolishness’

In 13 above, foolishness made Mne physically spread things in her house by scattering them everywhere. While 14 involves the conceptualization of the same movement of spread by scattering but within the psychological domain, hence, example 14 is the metaphorical extension of the concrete meaning of spread by scattering in example 13.

15. Iorwuese tough shima itoroun tuur ikyav mbi kpenga u oversaw ná gbá.

Iorwuese carry heart temper push goods of business of master his fall.

Iorwuese carry heart hot push-down (PAST) master load

[Literal:iorwuese carries heart hot push load of his master down]

‘Iorwuese pushed his master’s goods down out of hot temper’

16. Iorwuese tough shima itoroun tuur kpenga u overseen ná gbá.

Iorwuese carried heart temper push the business of the master his fall.

Iorwuese carry heart hot push-down (PAST) master business

[Literal: Iorwuese carry heart hot pushed down his master’s business]

‘Iorwuese pushed his master’s business down out of hot temper’

In 15 above, out of hot temper, Iorwuese physically pushed down his master’s goods. Example 16 involves the conceptualization of the same movement of pushing down but within the psychological domain, hence example 16 is the metaphorical extension of the concrete meaning of the push down in example 15.

Containment Schema

Johnson (1987) in Edeoga (2012) gives the example of the schema of containment, which derives from the experience of our human body itself as a container, from the experience of being physically located within bounded locations like rooms, beds, etc. and also of putting objects into containers.

Such a schema has certain experientially-based characteristics. It has a kind of natural logic, including for example the rules below;

a. Containers are a kind of disjunction: elements are either inside or outside the container.

b. Containment is typically transitive: if the container is placed in another container, the entity is within both as Johnson says: if I am in bed, and my bed is in my room, then I am in my room. The schema is also associated with a group of implications, which can be seen as natural inferences about containment. Johnson calls these entailments and gives examples as follows:

i.Experience of containment typically involves protection from outside forces.

ii.Containment limits forces, such as movement, within the container.

iii.The contained entity experiences relative fixity 0f location.

iv.The containment affects an observer’s view of the contained entity, either improving such view or blocking it (containers may hide or display).

The schema can be extended by a process of metaphorical extension into the abstract domain. Johnson (1980) identifies CONTAINER as one of a group of ontological metaphors, where our experience of non-physical phenomena is described in terms of simple physical objects like substances and containers.

The sentences below are used to demonstrate the correspondence of the verb root tuur to the containment schema.

17. Nguavese tuur naha shin tyégh gu naha ruam.

Nguavese pushes the turning stick inside the pot turning food.

Nguavase pushes rV PAST stick PREP inside the pot turning food.

(literal: Nguavase pushed stick inside the pot to turn fufu)

Nguavase turned fufu in the pot.

In 17 above, the pot is the container while the food inside the pot is the content and the content which is the food is inside the container pot.

18. Ankon tuur amisha sha nya shin tyégh.

Tree push roots at the soil in the pot.

Small tree push rV PAST roots PREP top sand PREP pot

(literal: small tree push root on top sand in pot)

The tree roots are on top of the sand in the pot

In 17 and 18 above, the sentences are fulfiling the two rules of the containment schema. In the first sentence, the element or content is in the container and the second, although the plant is in the sand the sand is also in a container. In the two sentences, we have observed different relationships between the entity and the container in the first the food is entirely contained in the pot. But in the second the plant depending on the size could grow beyond the top edge of the pot or even break through the pot.

Findings

Cognitive linguistics in general and cognitive semantics, in particular, is seen to have as its central concern the representation of conceptual structure in language. In line with this central concern and as a contribution to the ongoing research in cognitive semantics, the study examined the verb ‘tuur’ and found out that ‘tuur’ can adequately be glossed as ‘push’ in all the data, however, ‘tuur’ can be translated as ‘push’ in some instances, and so many other examples, the verb can be translated to mean use, pour, lock, compete, play, etc. By implication, ‘tuur’ has so many meanings associated with it; hence the verb is not semantic empty/dummy.

The conceptualization of the verb ‘tuur’ was analyzed with the image schema. The meanings fell into three broad image schemas: PATH, FORCE and CONTAINMENT. The image schemas of SOURCE-PATH-GOAL, show that our journeys have a beginning and an end, passing through places on the way. The study also observes that ‘tuur’ fits into four types of FORCE image schema: COUNTERFORCE, which involved the active meeting of physical or metaphorical opposing forces, ENABLEMENT, which derives from our sense of potential energy, or lack of it, about the performance of a specific task such as ‘push’, BLOCKAGE, a situation where a force meets an obstruction and as a result acts in various ways, and REMOVAL of RESTRIANT, a situation where blockage makes for the exertion of force to continue along a trajectory, we also observed that the verb root ‘tuur’ fulfils the rules of containment schema. Our analysis reveals that these image schemas of ‘tuur’ are conceptual constructs which can be metaphorically extended across a range of domains, shifting from the external and concrete to the internal and abstract domains.

As a contribution to the ongoing research on indigenous language verbs and cognitive linguistics in general and cognitive semantics in particular, the study has used the cognitive semantics approach to examine the Tiv language verb tuur, ‘push’ beyond the structure of the verb and into the psychological and abstract semantics of the verb as analyzed in this study. In addition, the study looked at the verb root as reflecting some specific patterns of conceptualization. Finally, this study employed metaphor and image-schema as types of cognitive structuring and examined how the concepts extended the meaning of conceptual interactions or structures in Tiv.

1.5 Conclusion

It is inspiring to think about all the possibilities language research can offer us for understanding human cognitive capacity. Finally, we can say that meaning is conceptualization, metaphor and image schemas extend the meaning of structures or sentences in language. This study is not the most detailed cognitive semantic analysis of the verb root ‘tuur’. Therefore more research on this topic and even other Tiv verb roots are encouraged.

References

1. Ayem, S. (2010). Tiv language in practice: A descriptive approach Makurdi: Gold Ink Company.

2. Cann, R. (1993). Semantics: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

3. Chomsky, N. (1976). Reflections on language London: Maurice Temple Smith Ltd.

4. Clauser, T. & Croft, W. (1999). Domains and image schema. Cognitive Linguistics, 10, 1-31.

5. Croft, W. & Cruse, D. A . (2004). Cognitive linguistics Oxford. Oxford University Press.

6. Croft, W. (1993). The role of domains in the interpretations of metaphors and metonymies. Cognitive Linguistics 4, 335-370.

7. Cruse, D. A. (1986). Lexical semantics: An introduction. Cambridge University Press.

8. Edeoga, P.N. (2012). The semantics of the verb –se: A cognitive semantic study. A PhD seminar paper Department of Linguistics, Igbo & Other Nigerian Languages, the University of Nigeria Nsukka.

9. Emenanjo N. E. (1975). Aspects of the Igbo verb. In. F.C. Ogbalu & E.N. Emenanjo (Eds.), Igbo Language and Culture (160-173) Ibadan: Oxford University Press.

10. Emenanjo, E. N. (1984). Igbo Verbs: Transitivity or complementation? A paper Presented at the Linguistics Association of Nigeria Conference held at the University of Nigeria Nsukka, 12-15 September 1984.

11. Evans V., Bergen, B. K. & Zinken, J. (2007). The cognitive linguistics enterprise: An overview www.vyvevans.net/CLoverview.pdf. Retrieved: 21 December 2012.

12. Evans, V. & Green, M. (2006). Cognitive linguistics: An introduction. www.google.ebook.com/books/isbn/0805860142 Retrieved: 16 December 2012.

13. Fauconnier, G. & Turner, M. (2002). The way we think: Conceptual blending and the mind’s hidden complexities New York: Basic Books.

14. Fauconnier, G. (1985). Mental spaces: Aspects of meaning construction in natural Language Cambridge: MIT Press.

15. Fillmore, C. (1975). An alternative to checklist theories of meaning Journal of Berkeley Linguistics Society. 1, 155-159.

16. Geeraerts, D. & Cuyckens, H. (2007). Introducing cognitive linguistics. In. D. Geeraerts & H. Cuyckens (Eds.), Metaphor and metonymy in contrast New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

17. Gibbs, R. & Colston, H. L. (1995). The cognitive psychology reality of image schemas and their transformations Cognitive Linguistics 6, 347-378.

18. Gibbs, R. (1994). The poetics of mind: Figurative thoughts, language and understanding New York: Cambridge University Press.

19. Haiman, J. (1980). Dictionaries and encyclopedias Lingua. 50, 329-357.

20. Jackendoff, R. (1990). The conceptual structure of verbs. MIT Press.

21. Johnson, M. (1987). Image schemas and the cognitive representation of spatial relations. Cognitive Linguistics, 1(1), 5-27.

22. Johnson, M. (1987). The body in the mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination, and reason. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

23. Lakoff, G. & Johnson, M. (1999). Philosophy in the flesh: The embodied mind and its challenge for Western thought. New York: Basic Books.

24. Lakoff, G. & Nunez, R. (2000). Where mathematics comes from: How the embodied mind being New York: Basic Books.

25. Lakoff, G. & Turner, M. (1989). More than cool reason: A field guide to poetic metaphor Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

26. Lakoff, G. (1987). Women, fire and dangerous things: What categories revealed about the mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

27. Langacker, K. W. (1991). Foundations of cognitive grammar 2: Descriptive application. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

28. Langacker, R. W. (1987). Foundations of cognitive grammar 1: Theoretical prerequisites. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

29. Lehrer, A., & Feder Kittay, E. (Eds.). (1992). Frames, fields, and contrasts: New essays in the semantic and lexical organization. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

30. Lobner, S. (2002). Understanding semantics. London: Hodder Education.

31. Mandler, J. (1992). How to build a baby: Conceptual primitives. Psychological Review 99, 597-604.

32. Mill, J. S. (1843). A system of logic London: Longman

33. Ndimele, O. (1997). Semantics and the frontiers of communication. Port Harcourt: University of Port Harcourt Press.

34. Nwachukwu, P. A. (1985). Inherent complement verb in Igbo. Journal of the Linguistics Association of Nigeria. 3, 61-74.

35. Nwachukwu, P. A. (1987). The argument structures of Igbo verbs. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Center for Cognitive Science, MIT.

36. Ogbonna, J. E. (2013). A cognitive analysis of the verb kwa. A PhD seminar paper presented in the Department of Linguistics, Igbo & Other Nigerian Languages, the University of Nigeria Nsukka.

37. Ogden, C. K. & Richards, I. A. (1923). The meaning of meaning. London: Kegan Press.

38. Rosch, E. (1975). Cognitive representation of semantic categories. Journal of Experimental Psychology 14, 192-233.

39. Saeed, J. I. (2003). Semantics. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

40. Sjostrom, S. (1999). From vision to cognition: A study of metaphor and polysemy in Swedish. In. J. S. Allwood & P. Greenford (Eds.) Cognitive semantics. Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing.

41. Talmy, L. (2000). Towards a cognitive semantics. Cambridge: MIT Press.

42. Talmy, L. (2011). Cognitive semantics: An overview. www.liguistics/buffalo.edu/people/talmy/talmyweb Retrieved: 21 November 2012.

43. Turner, M. (1987). Death in the Mother of Beauty: Mind, metaphor, criticism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

44. Uchechukwu, C. (2011). Igbo verbs and cognitive linguistics. Igbo Language Series 3.

45. Udu, T. T. (2009). Tiv language: A reference book. Kaduna: Labari Communications and Publishers.

46. Viberg, A. (1999). Polysemy and differentiation in the lexicon. In. J. S. Allwood & P. Greenford (Eds.) Cognitive semantics. Amsterdam: John Benjamin’s Publishing.

47. Zlater, J. (1999). Situated embodied semantics and connectionist modelling: Cognitive semantics. Amsterdam: John Benjamin’s Publishing.

No comments:

Post a Comment

ENGLISH: You are warmly invited to share your comments or ask questions regarding this post or related topics of interest. Your feedback serves as evidence of your appreciation for our hard work and ongoing efforts to sustain this extensive and informative blog. We value your input and engagement.

HAUSA: Kuna iya rubuto mana tsokaci ko tambayoyi a ƙasa. Tsokacinku game da abubuwan da muke ɗorawa shi zai tabbatar mana cewa mutane suna amfana da wannan ƙoƙari da muke yi na tattaro muku ɗimbin ilimummuka a wannan kafar intanet.